Click above to listen to this article as a ghost story. No need to wait for Christmas.

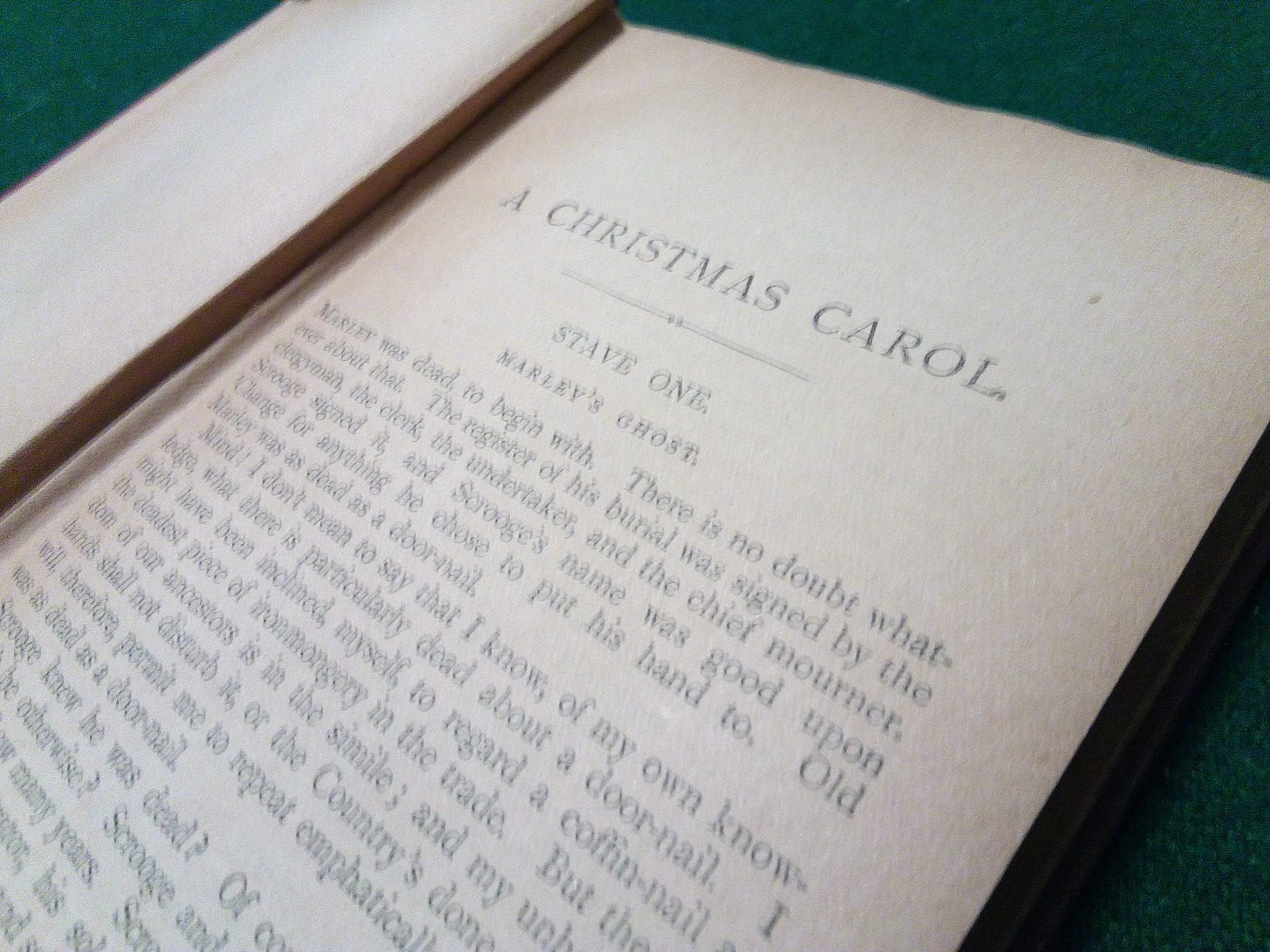

The word scrooge has entered common parlance to mean anyone who grumbles incessantly at the joyous occasion of Christmas. Over a certain age, that’s all of us, to some degree. It comes from the character Ebenezer Scrooge, the protagonist in Charles Dickens’s story A Christmas Carol.

This short story is famed for the visitations upon Scrooge, as he is conducted unseen into the past, present and future by Ghosts of Christmas, of which he is forwarned by the ghost of his deceased partner, Joseph Marley. They are not the only ghosts in this story, however; there are two more.

They were a boy and a girl. Yellow, meagre, ragged, scowling, wolfish; but prostrate too, in their humility … No change, no degradation, no perversion of humanity, in any grade, through all the mysteries of wonderful creation, has monsters half so horrible and dread.

Scrooge started back, appalled … ‘Spirit, are they yours?’

‘They are Man’s,’ said the Spirit, looking down upon them. ‘And they cling to me, appealing from their fathers. This boy is Ignorance. This girl is Want. Beware them both, and all of their degree; but, most of all, beware this boy, for on his brow I see that written which is Doom, unless the writing be erased. Deny it!’ cried the Spirit, stretching out its hand towards the city. ‘Slander those who tell it ye! Admit it for your factious purposes, and make it worse! And bide the end!’

‘Have they no refuge or resource?’ cried Scrooge.

‘Are there no prisons?’ said the Spirit, turning on him for the last time with his own words. ‘Are there no workhouses?’

What changed Scrooge more than anything was being shown the results of his own cruelty. Being tormented himself by words he used of others: seeing—in such munificent privilege—the consequences of the acts he engaged in as second nature, perceived by him alone as being … of no consequence.

Playwright and social commentator Edward Bond writes in A Short Book for Troubled Times:

In war, we praise an airman for burning children to death. When he comes home and kisses his own children he is praised for being a good father. But how can he then live with his own thoughts and feelings—he must deny them. But if he does that, how could he know himself? Surely his life cannot make any sense? He has lost his humanity.

Actor Dirk Bogarde recalls in his seven-volume autobiography how he served his nation as an air reconnaissance photograph interpreter in World War II. He recounts how he thereby took responsibility for the deaths of thousands and yet never looked a one of them in the face.

The difference between the proverb once bitten, twice shy and the contracting of venereal diseases is the immediacy of the danger. We learn quickly that flames are hot and therefore to give them a wide berth. But not all those who smoke catch cancer; not all those who have unprotected sex catch syphilis; and even if they, do, it’s curable. Aircraft plummet from the sky due to inattention by airmen placing excess reliance on automated avionics; already we’ve had the first court cases over driverless cars. When, shortly after their introduction, a woman died in a car crash in which, it was concluded, the airbag had actually caused her death, one road-safety expert made the wry, but true, comment that road safety would be greatly improved if all cars were equipped with a metal spike in the middle of the steering wheel.

What connects Charles Dickens, Edward Bond and Dirk Bogarde is the realisation of how easy it is to commit inhuman acts when we shield ourselves from their effects with an impenetrable blanket that prevents our seeing them. Even although we know they take place, we don’t see the effects of what we do, and therefore we pay them no heed. We are the only species privileged to interpose a blindfold between what we do and the effects of what we do. That is perhaps the reason why humans are capable of acting like animals, and animals are not. It’s not that we don’t see the wood for the trees; it’s that we don’t even recognise the trees for what they are.

When the wealthy and the mighty themselves, with air conditioning turning full pelt and still unable to maintain a commodious coolness upon their brows, succumb to the knowledge of global climate catastrophe, will they then wail, and gnash their teeth and complain loudly? “Why, oh, why, did none send to us emissaries like the Spirit of Joseph Marley, and thus forewarn us of the errors of our ways? Why acquiesced ye, so insouciant of our folly? Why failed ye to berate us for our idiocy? Why allowed ye those children of Man, Ignorance and Want, to rob us of our humanity?”

I agree. The rich make most lives so difficult that the rest are worried that the newcomers will invade their space to their detriment. The evil we know is better than the evil we can’t see… Humans are a sad species. Maybe climate change will rid the earth of their scourge. Hinduism says (I’m not one, so not 100% sure I’m getting this right) says we are in Kali Yuga where we have to live through dark times before the cycle turns positive again & man can again live in harmony & love with his neighbor. Sadly we have 400,000+ years to go …

Not much better/worse than the evangelist’s rapture scenario…