This article doesn’t in its entirety deal with the subject on which it homes in at the end. In a way, it circles overhead in languid trajectories across the sky, and some may even wonder if it ever lands. It does.

Image: a Pickup is a chocolate biscuit from the German company, Leibniz.

If I was asked to come up with a knee-jerk answer to the question “Why do the police achieve a conviction rate of under 1% for a crime of which a quarter to a fifth of all females will at some point in their lifetimes be a victim? then, it would be this: because they want to.

A crime as old as the hills

The subject is one that is touched on by Shakespeare in his play Henry V. The play is neither a comedy nor a tragedy, but is referred to as one of his histories. Because all historical figures eventually die at some point, a history may be regarded as a tragedy, especially if the protagonist behaves tragically, as King Lear did, who was a fictitious king. Henry V was not tragic – he was victorious! But he didn’t die at the end of his play. Not for a full seven years after that did he die, at Meaux, where brie comes from. All that aside, there is for me a big question mark over the play Henry V: for, though it’s a history in all senses, it contains episodes that do reek of comedy (it is censored—Shakespeare at no point makes even the slightest mention of the longbows that secured the English victory at Agincourt—it was written to please those in power in 1600, not 1415, and it seems to be 95% chit-chat and 5% battle, whereas the proportions are reversed in reality), At any rate, you would like to think of it as comedy, were it not in fact in one respect so tragic. This is what Henry says to the Governor of Harfleur, in wooing him to give up his defence of the town. It is a thinly veiled threat that secures Henry the port without a fight:

What is’t to me, when you yourselves are cause,

If your pure maidens fall into the hand

Of hot and forcing violation?

Therefore, you men of Harfleur,

Take pity of your town and of your people,

Whiles yet my soldiers are in my command,

If not—why, in a moment look to see

The blind and bloody soldier with foul hand

Defile the locks of your shrill-shrieking daughters.

Will you yield, and this avoid?

Or guilty in defence, be thus destroy’d?

The apparent nonchalance in Henry’s tone is indicative of the workaday function of rape as a weapon of war. Nothing has changed since 1415. When we come to look at the driving force behind rape, it’s not hard to see why that should be.

A good psychiatric joke

This guy goes to see a psychiatrist and the psychiatrist asks him, “So, tell me, what seems to be the problem?” and the guy says, “I think I’m obsessed by sex.” So the psychiatrist guy says, “Okay, I see. Tell you what, why don’t we do some tests?” So, the guy says, “Sure, why not?”

And the psychiatrist takes a pad of paper and a pencil and, on the paper, he draws a straight line and shows it to the guy and asks, “Tell me what you see.” And the guy says, “That’s a bed.”

So the psychiatrist takes back the pad and draws a square on top of the line, and hands it back and asks, “So, what is it now?” And the guy says, “That’s a naked woman lying on a bed.”

So the psychiatrist takes back the pad and adds a circle next to the square, and again asks the guy, “So, what do you see now?” And the guy says, “That is a man and woman lying naked on a bed, making love.”

The psychiatrist puts away the paper and pencil and turns to the patient and says, “You know what? You’re right: you are obsessed by sex!” The guy turns to the psychiatrist and says, “What, me? It’s you who’s the one drawing all the dirty pictures!”

Of course, there are some who cannot see a plain thing for what it is; and some just don’t get the allusion. Those who see The Haywain’s foreground man and dog as a bag of walnuts. Others see Mondrian’s entire life mapped out before them in but a single one of his works. And there are some in this world who’ll see a line drawn on a sheet of paper as representative of a bed and all the rest of it, and then feign that they see nothing of the sort. When all is “revealed” to them, and they finally “tumble” to what it is they in fact see, they have the, carefully reserved, option of feeling, oh, so stupid, or assuming the moral high ground. Perhaps snootily adding, “Well, I wouldn’t know anything about that.” Which just goes to show that you can in fact, and then to no little effect, gaslight yourself.

We see with our eyes and hear with our ears. But we cannot know whether the psychiatrist is being deceitful. If he’s not, it’s a good joke. If he is, it’s a case of medical malpractice. To know which he’s being, is it unreasonable to assume he will react in such a way as maximises profit? In the case of Cigna, in the US, that’s precisely what Dr Cheryl Dopke did: made medical diagnoses based on profit maximisation.

Victorian wokery: danger can be seen as plain as the microbes on your face

For years, no great advancements were made in the field of surgery. Then, scientific endeavour made inroads and people started to cut up the dead to find out what we look like inside. We knew more or less what people looked like on the outside, that men were different from women and man different from foxes and wolves, and things. From the art of dissection came the science of surgery. Still, a lot of advances remained unmade, because even cutting into a human body to see what all’s in there leaves a lot of it undiscovered simply because it’s too small to see or understand. Only microscopes would reveal the really small stuff.

Image: Joseph Lister, who advanced knowledge of antiseptics.

Even then, there was stuff so small, even a microscope couldn’t see it. Microbes and bacteria and things. When carbolic soap was invented and made available on a “try me, I’m free” basis at the entrances to wards in hospitals, surgeons proudly refused to bow to such pseudoscience papkak, vehemently declaring that what they could not see, could not be there. (Now, we have quantum physics.)

After all, had humankind not lived through the empirical Age of Reason, when tittle-tattle and superstition were put to bed for once and for all, and hard, observable fact reigned supreme as the prime evidence of what’s what and what’s not? (Like the eminently observable miasma, the stenchy air that circulates and cause diseases like malaria.)

The Age of Reason, or Enlightenment, certainly placed judicial proceedings on a somewhat firmer basis than they had been previously; and, wow, that must have come as a huge relief to the many thousands of witches who’d all been fearing a nasty end on some ducking stool. Of course, that’s supposing there indeed were any who needed to fear anything. For, if you can’t see magical powers, how can they possibly exist?

A fair encounter’s fair assessment

I once had a fling with a guy I met at a hotel in California. Upon removal of his shirt, I saw he bore an impressive panoply of tattoos. Really, quite impressive. The close inspection that the opportunity afforded me allowed me to glean information on some of the various messages with which his skin was bedecked. He was also complimentary about my own. When I asked where he’d acquired all these tattoos, he told me: “In the can.”

Ronald was a veteran of the Californian penitentiary system, and bore the marks to prove it. He was lovely, very personable and even asked if we could stay in contact. I gave him my telephone number, but I never did hear from him further. Ships that pass in the night. He did perhaps nick stuff, but not off me, off another visitor to our quarters, Alejandro, who was a bit miffed but acquiesced in his powerlessness to recover his allegedly mis-taken belongings.

The style I adopt in relating these facts, which are of passing interest only, reflects a wish to restrict the depth of the insight to what is needed to make my point. The names have not been changed, since my feeling is that reprisals are remote in the extreme, identity as good as anonymous. Nonetheless, a level of detail is retained in order to make the point aimed at, and it will follow. Ronald, who may or may not have been dishonest, had been quartered in a penitentiary at some time in his past for an offence of which I’m unaware. It is my lack of enquiry into his criminal past that at least, or so I believe, moved him to want to stay in contact – perhaps you think that that’s precisely why I ought to have asked. In that moment, I believe he was sincere, however. The loss of Alejandro’s belongings may or may not have been due to Ronald, but there is no evidence either way, not in my possession at any rate. A year or so afterwards, I met up with Alejandro again, and it was then that he related to me his suspicions about Ronald, by when there was no come-back possible. But on that second occasion, we still had a most pleasant encounter.

Alejandro does face massages, and very good he is at them as well. On the second occasion, he administered one to me. I later learned that he did so out of a degree of friendship but also for a very important reason of honour: he said “thank you.”

I will venture a posit: both Alejandro and Ronald, while previously unacquainted with each other, were nevertheless from within what one might criminologically call ‘similar circles’. They both live peripatetic lifestyles within a fairly close community, in the Desert Cities of the Coachella Valley. They order their lives within a system that may seem chaotic, by some standards is chaotic, and that works for those who work it. A bit like banking. They live pretty much hand to mouth and I’m not blind to the fact that, as a registered resident at the hotel, one of the prime attractions that I offered to both of them, on both occasions, was the simple expedient of a roof for the night.

Those with a criminal past or even a criminal present are generally advised against for company. Usually, because they have a tendency to commit criminal acts, and one doesn’t wish to put oneself between a criminal and his act. Criminals are rejected by wholesome society. There is a broader point to be made here, but I shall make it only in passing: if the criminally minded are ostracised by society to the degree of being excluded from its presence, then they are forced almost by default to circulate among only criminals. That is regrettable: the criminal justice system sets itself the aim of rehabilitation, and yet frequently fails in that because that aim does not resound with the greater population whose protection it is instituted to ensure. Criminal justice bends to the effort of rehabilitation, only eventually to be confronted by a general sense of rejection by the very general public in whose behalf the system had even bothered to make the effort. Reintegration is a very rare circumstance.

Image: The Coachella Valley, marked by its nine Desert Cities. I have vacationed here on seven or eight occasions and I would return tomorrow. I even have a frozen membership at a local gym here: home from home. The scenery is majestic and awe-inspiring even to those born and bred in this area. Sunset is an artist’s palette. The valley is two hours’ drive from Los Angeles, and a world apart.

“City” is a loose term here: the whole nine of them have a total population not above 350,000, so around 35,000 each. Aside from the settlements, most of which date from the 1930s, which is almost unbelievable when one considers the lack of air conditioning at the time, the countryside is sparsely populated, with large tracts of barren, rocky ground. The only farms in the valley harvest wind, for green energy. The settlements themselves rejoice in relatively uninspiring names, which I see as having been plumped for barring any other identifying feature, and include such distinctive names as Palm Springs (a spring with palms), Palm Desert (no spring, palms and the usual sand), Desert Hot Springs (a spring again, a bit warmer this time, and sand again), Twentynine Palms (someone clearly counted this lot) and Thousand Palms (nobody, I reckon, actually counted them), plus an intriguing name for the casual visitor: Cathedral City.

Cathedral City has a population of 60,000, but is around half the area of nearby Palm Springs: Palm Springs was the resort escape for Hollywood celebrities (Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Gene Autry, Bing Crosby, Jack Benny, Barbara Stanwyck – just read the street names); Cathedral City, on the other hand, was where the workers lived, mostly of Hispanic origin: Rancho Vista, Paseo Real, Pueblo Trail. This lends the two localities quite contrasting looks & feels and cultural experiences. There is no cathedral in Cathedral City, nor was there ever one. When early explorers came to the Coachella Valley, they were shown a wonderous and revered holy site by local First Nations. It was the awestruck explorers who likened the geological formations in the canyon to a cathedral, and thus gave it the English name “Cathedral Canyon”. The City followed afterwards.

In the picture, we see the eastern outskirts of Palm Springs, the main town centre being nestled further in the shadow of the impressive Mount San Jacinto (the mount of Saint Hyacinth of Caesarea), which stands 8,300 feet prominent compared to Palm Springs and at 10,833 feet altitude from sea level. In summer, temperatures in the town reach the mind-boggling and easily remembered “1-2-3” – 123° F, or 55° C. The climate is, as one might expect, “desert”, which brings with it all the usual trekkers’ admonitions about hydration and always carrying water when out and about. Cellphone coverage can even be patchy. As a relief from the sweltering summer heat, entrepreneurs in the 1960s built what is called the “Palm Springs Aerial Tramway”, which is not a streetcar but a cable car, which can be walked around as it rises, and rotates on its axis to afford visitors an all-round view of Chino Canyon. Mid-summer temperatures at the summit, which is walkable with pleasant woodland treks, quite easily done for the average Joe, are much cooler, at around 20-30° C. But you need to remember a pullover or jacket, which isn’t always the first thing on your mind as you swelter queuing for tickets down at the home base.

Over the past ten years, humidity in the Coachella Valley, which is otherwise famed for its music festival at around Easter time (with a segue into the most amazing musical experience in the world at the Palm Springs White Party), has gradually risen and this can make the high summer a little less comfortable, since the regular dry heat is actually fairly bearable. The moisture is being contributed, according to the manager at the All World’s Resort complex, by “the 2,000 golf courses that have sprung up in the valley.” I ventured a correction: “You mean 2,000 holes of golf?” “No,” came the reply, “2,000, 18-hole golf courses, which all get sprinkled to keep them green in this barren desert.”

I’ve become friends with many locals, few of whom were raised in Palm Springs, however. They are extremely gregarious and reach out to relative newcomers they encounter with a question I have heard so often repeated, it makes me smile each time: “How did you survive your first summer in Palm Springs?” On one visit, my room’s air conditioner promptly ceased working and I reported the matter to the desk clerk the next morning. I then took myself off to fill time with a visit to the tramway. Anxious to inform me of progress in finding an engineer (who, I was amused, spoke Spanish and very little English, but knew all about HVAC), the cleaners had been issued with a description of my appearance and had proceeded around the complex enquiring with potential candidates whether they were “the gentleman from room 10”. All was regaled to me upon my return at lunchtime, to which I replied, “I didn’t realise that tourists aren’t supposed to go off doing tourist things …” They upgraded me, I think to cut a divide in the process and stop me being “that man from room 10” for the rest of my stay.

Defining who is worthy of being adjudged “dangerous”

So, by now, I have stretched the reader’s curiosity to breaking point: what has all this to do with psychiatrists and microbes and surgeons? Here, for the patient, is the point I promised to make earlier.

Ronald wears, his body over, the emblems that mark him out as a criminal. They are there for all the world to see, at least when he undresses, but even before he does, as they extend onto his collar-area. Why does he do that?

There may be several reasons. Maybe he is proud of his criminal associations. More than just a baseball fan who wears a Dodgers cap, or a parent who buys a Mickey Mouse tee shirt for their son, or a Belgian who displays the “B” symbol next to his number plate on his car. Pride in the association. Without actually working for the Disney organisation or playing baseball or even – who knows – being from Belgium. That could be it, even if the association is real: like some old school tie.

The degree of shame or otherwise that Ronald feels for his misdoings and for the time he spent in prison as a result of them is something I cannot and won’t judge. For sure, he wasn’t abashed when he revealed his tattoos; they are as a bent nose would be to a boxer: something that he lives with and is part of who he is.

If a white-collar criminal were sent to prison for financial crimes, would he or she likewise acquire tattoos to attest to their criminality? I don’t know to be honest but the mere idea has me tending to the “unlikely”: in fact, quite the contrary, they would, upon their release, probably want to draw a dark veil across that part of their life, and reveal it to nobody who doesn’t need to know. Whether that would indicate a desire to turn a new leaf or whether that would mean they wished to beguile new people with their financial trickery and return to the old lifestyle, even if in a somewhat more circumspect manner this second time around; those, too, I cannot nor will not judge.

But Ronald, for the rest, I can judge. I met him. I spoke to him and I saw his tattoos. And what do I have to conclude about him?

Of all the people reading this, I can place a wager, on which there is undoubtedly some element of risk but which, if I lost, would be due to the most extraordinary of circumstances: that no one reading this has ever met Ronald, bar myself. What is possible is that someone reading this also knows a third party who bears such or similar tattoos, and who could offer more information to me to allow me to draw a different conclusion or to indeed amend the one I have. But, assuming that nobody has in fact met Ronald except me, any conclusion that the reader might have already formulated or is in the process of formulating will be based on an extrapolation. But of what?

An extrapolation is the drawing of a conclusion from empirical or theoretical bases, which apply by extension or analogy to an as yet unconsidered case. So, a conclusion about Ronald could in fact be drawn from the unlikely event that the reader has met and interacted with Ronald. Or it could be from their experience with “people such as Ronald”; but that would fail, on the basis that one cannot know whether other people are or are not like Ronald if they haven’t met Ronald. They could also be based on stories that they have heard about the type of people that Ronald and others are. Or from books or from newspaper reports or even from films and theatre plays. On some basis that fiction tells us more about reality than reality does. And yet I must put it to you that, since the Enlightenment, we should by now have dispelled from our minds any notion that that which cannot be seen can be appreciated and that what we understand must be based on what we see.

Ronald’s appearance is a token of the danger he may pose to those who meet him. One school of thought will err to the view that that which is dangerous should be avoided. Another, to the view that the appreciation of danger is a matter for the moment, and the response cannot be blanket but focused on the question of a danger to whom? Had Ronald brandished a gun at my address, I would have had a fairly immediate answer to the question of to whom the danger was posed. But he didn’t; instead, he brandished, if brandish them he did, his tattoos. Ronald is of a type who displays to the world what he is but doesn’t display what he is to all the world; and nor does he display to the world the sum total of what he is. Ronald is very similar to all of us. My endeavour is not to belittle the danger that criminals can pose; it is to stop and question what it is that makes us enter certain situations with a heavy bias to one side or the other.

It is not to say that I go blithely through the world and gladly cross paths with criminal types and take it on trust that I will come to no harm. I am circumspect and I am careful and, when a stranger is in my hotel room, I certainly keep a close eye on my belongings. The police, whose job it is to take measures to counter criminal acts are also similar to all of us. Their experience of the criminal fray makes them more attentive to situations of danger. They also, while requiring to be even-handed, will need to judge a situation for what it appears to be, rather than what it is. Modern policing is getting worse at that: the police, instead of getting better with experience, are getting worse, allowing deaths to occur whilst making arrests. More and more often. Perhaps they’re over-reacting. Perhaps unintentionally. Maybe they’re afraid. Maybe they’re getting an upper hand.

If it was the Age of Reason that heralded the age of even-handedness, then we are currently slowly teetering into the Age of Unwarranted Attacks and their close partner in crime, unwarranted retaliations: these heralded, somewhat sour-notedly, by the likes of QAnon, Kanye West, the Grand Old Party of the US, and a recoil against wokery elsewhere. Just as the inventor of carbolic soap tried to impress on the surgeons of Victorian England, that dangers can lurk where they cannot be seen, I am convinced that safety, too, can lurk where it can’t be seen, especially when danger is flagged for all to see. Carbolic soap was Victorian wokery.

And, now, the audience has a sharp intake of blood

Let us look at another criminal, for whom justice had no process and whose demise was only secured by hammering a wooden stake through his heart: Dracula. Several years ago I travelled to Antwerp to see a production by the British & American Theatre Society (ahem, BATS, for short) of the stage play Dracula, which is based on the book by Bram Stoker. By coincidence it was a play that I had myself had a part in at a play reading at a private house in Brussels, organised through the English Comedy Club. At the reading, we had engaged with this stage play very much in the style of parody by taking an overemphasised cautionary stance as regards the darker elements of the story. When it came to watching the play in Antwerp the emphasis got reversed, back to what it had been when the play was written. The story of Count Dracula has been recounted many times on the silver screen, to the point where the general public is, at last, able to see the funny side of this Victorian gothic drama. It’s closely associated with the Victorians’ prepossession with mortality, death and ghosts, and the very close relationship the Victorians had to death at a time when infant mortality was at very high rates and longevity more seldom than it is in our present age.

What became clear to me during the performance of the play, and which, perhaps unnecessarily, was re-emphasised when the cast assembled on stage to take their curtain call, was the very mortal danger that Count Dracula poses, of which we, the audience, are more than aware when the story starts but, as the plot progresses, the characters only gradually become aware: it’s an audience privilege that we, as the audience in everyday life, rarely get insight of before the real-life likes of Count Dracula end up on a charge in a court of law. The very prospect of Count Dracula manacled in chains and shuffling into the dock to be arraigned on a charge of blood-letting, raises an inward smile: it’s not a tack that was ever taken by any film-maker wanting to give insight into the genre, but it is ripe for parody: “You are hereby charged that you have on repeated occasions not been seen in a mirror and have been a bat.”

Stoker didn’t write his novel as a courtroom drama, but the Count is a character whose very existence is a figure of fantasy, possessing very non-human powers and a propensity to commit a very non-human crime. Supposing, for the sake of argument, that being a bat were to be enshrined in statute as a criminal offence, how much evidence of its actual commission and its prevalence, to some degree or another, in society would be needed for people at large to stop smirking when they heard it read in a court charge sheet? It’s when we consider how strange the words crime against humanity or genocide rang in ears only a few short decades ago, and how all-too familiar the terms are in our modern notions of the judiciary, that we get some small idea of what Stoker was about when he wrote his tale: about introducing people to the very idea of a crime beyond the farthest powers of their imaginations.

I told you that I was unaware of what crime had seen Ronald incarcerated. I therefore cannot warrant to you that it was not the crime of genocide, or a crime against humanity, as those terms are defined in the Rome Statute, which was passed 25 short years ago. Short years, but surely a quarter of a century of getting our minds around a new-fangled form of prosecution, has given us an idea of the kinds of people who commit crimes against humanity? My private suspicions are that they probably have one thing in common: they aren’t festooned with tattoos they acquired whilst “in the can”.

If I have to draw an obvious conclusion that aligns with what has gone before in this article, it would be to say that the most dangerous criminals who will ever cross your path will rarely if ever be wearing tattoos acquired during a previous sojourn at a penitentiary. That is ultimately what Stoker was trying to tell his readership: criminals don’t tend to act like criminals. So, how do you know they’re criminals?

The writings and times of Dorothy L. Sayers

From criminality, let us move on now to a crime writer: Dorothy L. Sayers. Before Sayers moved full time into writing about the exploits of Lord Peter Wimsey, she worked for a while at an advertising agency in London. Her experience in the advertising sector led her to write a Peter Wimsey novel about the industry (Murder Must Advertise) and to formulate a deep-seated mistrust and scepticism concerning advertising, which she described as follows, drawing an analogy with bread-making (an analogy she frequently drew on in her writings):

Of course, there is some truth in advertising. There’s yeast in bread, but you can’t make bread with yeast alone. Truth in advertising is like leaven, which a woman hid in three measures of meal. It provides a suitable quantity of gas, with which to blow out a mass of crude misrepresentation into a form that the public can swallow.

In case you’re wondering, Sayers knew her Bible: the hiding of leaven is a parable cited in the Gospels of the New Testament. The Gospel writers actually compared leaven to the word of God, which is not what Sayers compares it to, even if advertisers do.

If you wish to avoid yourself the pain of weeping for lost wisdom, then you should avoid learning of the fire at the Great Library of Alexandria, avoid studying the burning of the books in Nazi Germany, and avoid perusing the non-fiction writings of Dorothy Leigh Sayers. Otherwise, read, revel and mourn.

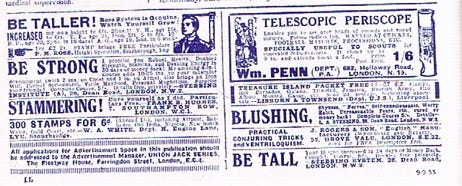

The important point here is that advertising does not lie. Well it does, but in most cases it soon gets hauled over the coals for doing so. That’s because we have advertising standards agencies, whose job it is to reprimand advertisers who stretch the truth or tell brazen untruths. But if you leaf through the pages of magazines from 100 years ago or more, you’ll encounter the most outrageous of claims by advertisers printed and paid for for the entire readership to see and nothing was ever done about those. The more outrageous the claim, the more desperate the reader is likely to be before he will tend to believe the claiming and subscribe to the product that’s advertised. Cures for stammering, blushing, ailments of every kind, flat-footedness, balding, you name it: for every ailment there was a miracle cure and, of course, for a cure against balding, only the balding were avid in an age where hair was the fashion to subscribe to products that claimed to prevent it. Dorothy Sayers lived during the Nazi age and must have been all too keenly aware of the outrageous claims being made by the German government at the time and the concomitant release that the German population felt when they subscribed to the party that would pursue the outrageous solutions to these outrageous claims. In so far, Adolf Hitler was right: the more outrageous the lie, the more readily it will be believed, provided those who believe are desperate enough to believe.

Image: these ads are taken from a facsimile edition of The Magnet, a boys’ magazine published on 9 September 1933. What schoolboy back then didn’t already make his own periscope? I do like the claim that one can be taller in 14 days, or money back. I presume they’re platformed shoes. The Stebbing Institute also offers strength, and more than that, promises it. It has to be said, The Magnet was aimed at a readership aged between 8 and 18. They were young males, who do as a rule have a propensity to surge in growth and strength during their adolescent years …For my money, it’s the practical conjuring tricks that win. Nice, that, being practical and all.

We believe what is proclaimed high and wide. Cognisant of the lessons from carbolic soap, that which we cannot see, we are prepared to be told we see. Like lambs to the slaughter (or tame Victorian surgeons, if you will), we are prepared to unhitch our own impedimenta of moral outlook, principled belief and faith in Him above, to subscribe to what an arrant liar is prepared to tell us, that, even if we don’t, we see before our very own eyes: even if we cannot believe our ears, we are prepared to exercise persuasion over our eyes.

If the proverb once bitten, twice shy holds true, then perhaps we’re less easily beguiled than were our forefathers. When little old ladies were deceived at the front door by tricksters who claimed to have been sent by the water board, the water board introduced identity badges, which they would issue only to their own bona fide staff and exhort customers on the doorstep to demand to see, as a measure against the trickery. Do you know what a water board identity badge looks like? It is seemingly easy for the same tricksters to manufacture badges with every sign of having been issued by the water board.

For every bluff there is a counter-bluff, and for every counter-bluff there is a plain lie. Those who prefer to avoid the company of criminal types dismiss the concerns of those who entertain such company, but often do so with cautionary phrases such as, “If you want to associate with them that is up to you; just don’t bring them here. I don’t want anything to do with them.” Yet, having nothing to do with them doesn’t make them cease to exist. It’s like the mantra on how to avoid being burgled. You make your house burglar-proof to an extent that the house next door is not: you don’t stop the burglary taking place; you move it to the next house.

Advertisers are not criminals and they don’t easily fall into the general category of what we regard in common parlance as being evil. I don’t believe that Ronald was evil, still less Alejandro. Not on the commonly held definition of the term. When we use the word evil, we conjure in our minds an image of a red-coloured, horned creature from hell, we conjure up images of Idi Amin, Pol Pot, Adolf Hitler, Vladimir Putin: in short, we ascribe the term to the worst of organised criminals, warlords, warmongers and incurable patriarchs, like the Iranian government.

We certainly do not hold to the view that anything like our concept of evil could exist within us: we are not greedy, we do not exploit others, we do not seek to enslave other people for our own material gain, not one bit of it; and, if others do that, then: do not bring them within my sight. Keep them away from me, I will not tolerate such people in my presence. Well, before we rejoice in such sentiments, allow that we stop for a moment and look again at what is actually meant with this word evil.

The common conception of evil is the will to occasion, or insouciance at occasioning, harm to others, whether for material benefit or otherwise. But that is not what evil is. When evil occurs, those of belief implore God and seek to know why it is that God allows evil to wreak its havoc. I don’t think that God allows evil at all; it’s just that He cannot stop it. We are, as human beings on this Earth, free agents: the only two things that restrict our movements and interactions with one another and with the natural world comprise, one, the Earth’s geographical boundaries – its mountain ranges, oceans, rivers, the physical features that we are unable to cross; and, two, the laws that are imposed on us by nation states. These two things are the only things that restrict our abilities to do either good things or bad things.

There are bad things which are permitted under the law and there are bad things which are not constrained by the physical features of our topography and which are left to our moral consciences. And these we exercise at our discretion. It is this exercise of our discretion that is the fundament of our relationship to God: God prevails upon us to avert acts that will, if consummated, occasion harm to people. What the devil does is not prevail upon us to occasion harm: the devil is as averse to harm as God is – intentional harm, that is; but what the devil will prevail upon us to do is to expunge from our considerations when formulating an intention to act any account we might otherwise take of what we’re doing possibly being a source of harm to another. Whereas God impresses upon us to do unto others as we would be done unto ourselves, the devil effectively says, “Do unto others without regard for whether that harms them and, if it does, be ready at home with a big gun.” The religious mantra of love others as you would love yourself is viewed by some as a position of weakness, since you have no guarantee at the time of loving that the others whom you love will in fact love you back. No such risk is encouraged in Satanism, which decrees that you need to give nobody any love but that you may not expect love back from them, either. And, yet, a world in which we would all be satanists and live this philosophy of looking out only for one person, being ourselves, and in which we could not in any way rely on love, kindness, respect, reciprocity of sentiment being shown by any other living being, would make this world a very different place to what it is even now. To that extent, even if we have no hard and fast guarantee that the love we receive is exactly equal in amount and intensity to the love that we give to others, it is that quasi-religious sentiment that in fact makes of our world a far safer place than it would otherwise be. Not weakness, but in fact strength.

I said that there is bluff, double bluff, and lies. I once pondered why our classic image of the devil is of a red skinned demon with horns on his head and why our classic view of Jesus, of God, is this benevolent, white-haired old gentleman in flowing robes looking down on our world from a cloud on high, surrounded by glorious angels singing his praises. If the devil is as duplicitous as we take him to be, why would he not impress upon us this image of him as being the white-haired old gentleman looking down benevolently on his people? In other words, why would he not pull a PR stunt? How do we know he hasn’t?

In the world of espionage, nothing is what it seems: a perfectly ordinary businessman could in fact be a spy. And a spy could even be a double agent. But, until we know that, we don’t know it. There must be some means of discerning when someone is true, is honest, is really what they give themselves out to be. It could be an identifying mark like the thunderbolt that Harry Potter received in an early encounter with Voldemort. Or a shibboleth, a word used by speakers of Hebrew to prove one way or the other whether their interlocutor is a true Jew or not.

The old saying goes that birds of a feather stick together or to catch a thief you need a thief. Well, maybe the justice authorities know who’s a thief and who’s not; but, do you? No, nor do I; but I have a hunch.

President Donald Trump has in a way misfooted the general public with his announcement that he wishes to be brought before the court of justice that will hear the case against him for having once bribed a pornographer while manacled in handcuffs (in case you just misread that sentence, go back and re-read it, would you?). I have read at least one piece in which a journalist says that he has looked forward to the moment at which he would see Donald Trump in handcuffs for many a long year. So does Mr Trump’s wish to be seen in handcuffs inspire joy in the journalist or trepidation? I think the journalist needs to revise his aspiration and formulate it as his desire to see Mr Trump in handcuffs at the behest of law enforcement and not Mr Trump himself; since, at Mr Trump’s behest, there’s at least a suspicion that to comply with it would be to indulge him in a PR exercise. Mr Trump is not a spy: we do not have to work out whether he is working for our side or the other side; what we have to work out is what his ultimate aims are and, for all he’s been patently clear about them for a good number of years, there’s still at least a question mark over what they are in the detail. What can we believe? Can we believe what we see? Or must we believe what we hear?

In the criminal world recognition is every bit as difficult as it is in the world of politics and as it used to be in the world of advertising; but there are clues. The first: to be bestrewn with tattoos is no guarantee that the wearer of the tattoos is still criminally inclined. The second: nor is it a guarantee that the wearer of the tattoos is a safe acquaintance to make. The third: nor is it a guarantee that what he is now, he will always be in the future (except that we must reconcile that third clue with the saying that birds of a feather stick together).

Set a rapist to catch a rapist

You can’t do that, of course. But you can get inside the mind of a rapist. That is the science of criminology.

There is currently an investigation ongoing across England and Wales, in which a large team of 54 criminologists are delving into police files in order to find the very complex answer to a very simple question: why are rape convictions so low? They are low: about 1% of all reported rape cases result in a conviction; and that is a pitiful conviction rate. The criminologists have been given wide-sweeping powers and prerogatives to provide this complex answer and, even as they do so, are being parried left, right and centre by political blame-mongers, credit-claimers and a raft of misogynistic, self-protective statements and acts, which are going around the houses and did, for a while, go around Mr House, an important London policeman.

It almost beggars belief that the simple definition of rape, which is penetration without consent by a male of another male or a female, should, since it was ever incorporated into statutory criminal law, have been the subject of so much debate and contention. This investigation, it is hoped, will clarify some of what has not been understood and some things of which there has as yet been no understanding. The misunderstood and the unknown.

Wayne Couzens is the London Bobby who was convicted and sent to prison for the rest of his born days for the rape and murder of Sarah Everard. The fact of an active police officer committing such a heinous and cruel crime sent shock waves around the world. Women in England came to a stark realisation: they could place no faith in the police. Either to investigate crimes against them; or not to commit such crimes.

The then Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, Mrs Cressida Dick, advised concerned women who were under attack from wayward police officers that they could easily flag down a passing double-decker bus. The crassness of such advice would lead to Mrs Dick’s resignation.

Actually, buses don’t run over most of Clapham Common, where Ms Everard was kidnapped, or in Hoad’s Woods near Ashford, where her raped body’s remains were found, having been ignited by her murderer. So, the buses weren’t brilliant advice, anyway. And they weigh about 12 tons, though drivers are used to stopping them. Mrs Dick’s contribution was to pour oil on flaming oil.

There’s an old saying in America, I believe, that, if something looks like horse-s**t, smells like horse-s**t and, perish the thought, tastes like horse-s**t, then it usually is horse-s**t. Recent experience, however, has told me the opposite in so many ways. That a vaccine does not inoculate you against the target virus. That a war is a special military operation. That a New York congressman’s CV can be a pack of lies and the congressman can remain in office. That we don’t need to learn from history because history got it wrong. That you can leave the European Union and retain an open border with the Republic of Ireland. That princes of the realm can be honest whilst taking brown paper packages of slush money or indulging in sexual acts with those with whom such acts are forbidden by law.

Rape does not have nothing to do with sex: it is quite patently a sexual crime. Most sexual crimes entail a want of consent on the part of one or the other parties; in short, they’re acts that are proscribed out of considerations of decency, morals and perhaps even medical safety. Man may not copulate with an animal. Man may not copulate with another human being who is deemed by law incapable of giving consent. The lack of consent is presumed and, so, therefore, the act is non-consensual and, therefore, the act is illegal. We cannot be as mindless victims of our caprices, whims and feral desires. All of this is true and, yet, how many rapes are committed in which sexual gratification is the desired goal of the tortfeasor? I wonder if anyone ever asks them.

There are multitudinous ways in which to satisfy one’s sexual desires: Onan invented the first. There is dating, whether speed-dating or in trendy bars, in discotheques or online websites. For the incurably ugly, there are prostitutes. The risk associated with consummating the act with a prostitute is far less than the risk associated with consummating it with a non-consenting, random partner—or so one would have thought. But prostitutes are eschewed by rapists, at least for the act of which they’re charged, and I know why. It’s not that they baulk at paying the money. It’s because of what the money means.

Rape is not the most obvious outlet for sexual gratification. Otherwise, I presume, there would be far more instances of it. But what rape is an outlet for, for which there are few other outlets, is as an exercise in power. Sex is not the goal of a rapist; it is the exercise of power over another human being that attracts a man to the crime of rape. The sexual act itself brings with it certain bonuses: a girl or woman who appears outwardly respectable, self-confident even, may be taken to have a balanced life, a happy life, a good job. Maybe in an office as a secretary or a young professional, will wear clothing that, even if it doesn’t overtly suggest loose morals, will be smart and attractive; she will have lingerie that emphasises her curvaceous form: these are little things rapists will be attentive to (after all, you don’t want to exercise power over someone who, in political terms, is like a puny little mountainous state that means nothing and whose name the rest of the world can barely pronounce: it must be a prize).

But, more than that, this target can be conjured to have a steady boyfriend: who plays in the rugby club or is a PhD in mathematics; or a husband who, regular as clockwork, comes in the front door every evening at six o’clock and cries out, “Honey, I’m home!” For this boyfriend and for this husband, the matrimonial bed is an exclusive arena of intimacy, where the partner, and he alone, may partake of the voluptuous curves that are only suggested in this young lady’s attire. By entering this domain without consent, the rapist rapes not only the woman, but also her boyfriend, her husband, her children; and she cannot hide the fact, like she can hide a dent on the bumper of her car: it is as if they stand and watch, powerless as the rapist takes what he wants. In the Ukraine/Russia conflict, many rapes were indeed committed in front of the parents of children subjected to the outrage, with first the victim of the rape being shot dead, and only then the parents suffering the same fate—who exercises power more than a soldier on a battlefield?

The more he’s abhorred, the better the rapist enjoys it to make himself abhorred. Abhorrence is his ultimate perversion. He does not ask permission, he does not ask licence, he does not ask anything: he takes because it is his; it belongs by rights to him, and anyone who naysays that shall be eliminated. That is the rape mindset. Not one of sexual desire, but one of power and dominance, shrouded in impervious untouchability.

Ms Everard’s uncle, when asked about her disappearance by the Evening Standard newspaper, said he had previously feared she’d been abducted by bad people but was left shattered by the news that a serving police officer was arrested for her kidnap, rape and murder, with the words, “It’s difficult to get your head ’round.” I sympathise with that: how can one who is appointed to serve and protect instead be guilty of the very crimes he should be protecting us from?

Those who would perpetrate the crimes that invade most crassly into the personal sphere, be it physical, financial, or a duty of care, will always aspire to the trust, confidence and lack of suspicion that surrounds the professions by which such trust is gained, be they scout masters, sports trainers, teachers, managers of orphanages, bank clerks, even shop assistants, or police officers. That may sound disingenuous, but it’s easier to get your head ’round. The reporter Melissa Denes, who tells the story of the current investigation by criminologist Betsy Stanko, says,“Part of what shocked me about the protests that followed Sarah Everard’s murder is that so many people clearly had had faith in the police.” Perhaps it’s not before time that that faith has been shattered.

To this comes the fact that those who, under duress, deliver up to hostage-takers the secrets of bank accounts, vaults, valuables, whatever, rarely do so in order to save themselves from the hostage-takers’ wrath, for their sense of duty is often greater than that; they do so because the hostage-takers know where their family is to be found, and that will surpass the duty of most to simple money. They reveal secrets not to save themselves but to save their children and it is for that reason that rapists rape: it is not the women themselves who excite these men; it is the exercise of that power over their nearest and dearest.

It is knowing this that convinces me of why so many law enforcement agencies are so ineffectual at enforcing this law, at investigating rape—either because they do not know this—have failed to recognise it—or—hope against hope—they have, indeed, recognised it, for it does take a thief to catch a thief.

There is no body of civil society that has more potential to take the law into its own hands than the police. The fact that some appear whimsically prepared to actually do so for a capital crime, and that others in their ranks are prepared to cover up out of a distorted perception of who the heck it ultimately is that they are under any duty to protect means that Stanko’s task cannot simply be to beef up how police investigate rape, but must also encompass how to beef up the very process by which trust is invested in a police officer. This special investigation may reach a good many conclusions that are not wrong. I do hope it will not fail to hit this mark, by recognising its distinct and rotten odour.

If police cannot be trusted, then we cannot be trusted

We are not blameless in this, as I try to stress: some blame lies with me and with you, with our society and with our social mores. For, without a society that functions as a society should, its mores will never be social of stature.

If you’re a rapist, I will not eschew you. But I will not protect you. If you’re not a rapist and you seek justice for the many, many women who are victims of sexual assault or rape, you will not achieve justice as I know it by taking your own mob’s vendetta justice in half-proven and wildly imagined cases. It is a question of fact: some of us have raped. Some of us have not. So we can posit a world split between rapists and non-rapists. By law, he who rapes is liable to the punishment for his crime, and he who does not, is not liable to punishment. Because the law will judge whether or not you did the act, and not what you planned or intended or whatever, or by what self-restraint or constraint you did not procure the act.

But suppose we were instead in a world not of rapists and non-rapists but of Pickup-bar eaters and non-Pickup-bar eaters. If I miss the analogy that will entice you, use your imagination: for there are those among us who can happily walk past a 12-metre supermarket display from floor to above head height of nothing but Pickup bars and yet leave a store without making a single purchase. They possess the patience of Job, the steadfastness of Moses, the endurance of our Lord Jesus Christ. And then there are those who must observe a strict regimen that keeps them from ever approaching an unprotected Pickup bar; who, perhaps and cognisant of their weakness and will, implore their friends to physically restrain them as they perambulate past confectionery outlets.

Some abstain for want of will. And others abstain in a super-human effort to abstain. The will to control and exercise power that is unleashed by a rapist is not, I believe, whimsical in character. It is pathological. Not an uncontrollable urge, but one to which resistance is gladly dismissed.

If we can say this about rape, we can say it about many other manifestations of power in our modern world that are less easily laughed off as a chocolate confection. Where the duty is not owed to law and order or to a bank vault’s combination but to whether or not advantage should be taken to raise the price of an already overpriced commodity with the sole aim being to simply further enrich the producer’s owners and management. And the fact that that conundrum should be afforded any serious consideration in the first place suggests to me that, as a society, we still aren’t able to pass a Pickup bar by.