On 21 October 1805, Horatio, Admiral Lord Nelson, commanded his flagship and fleet in a final, decisive sea battle to put the cap on any invasion of Britain by the vastly superior joint French and Spanish navies, named for the Cape of Trafalgar, just south of Cadiz, in Spain.

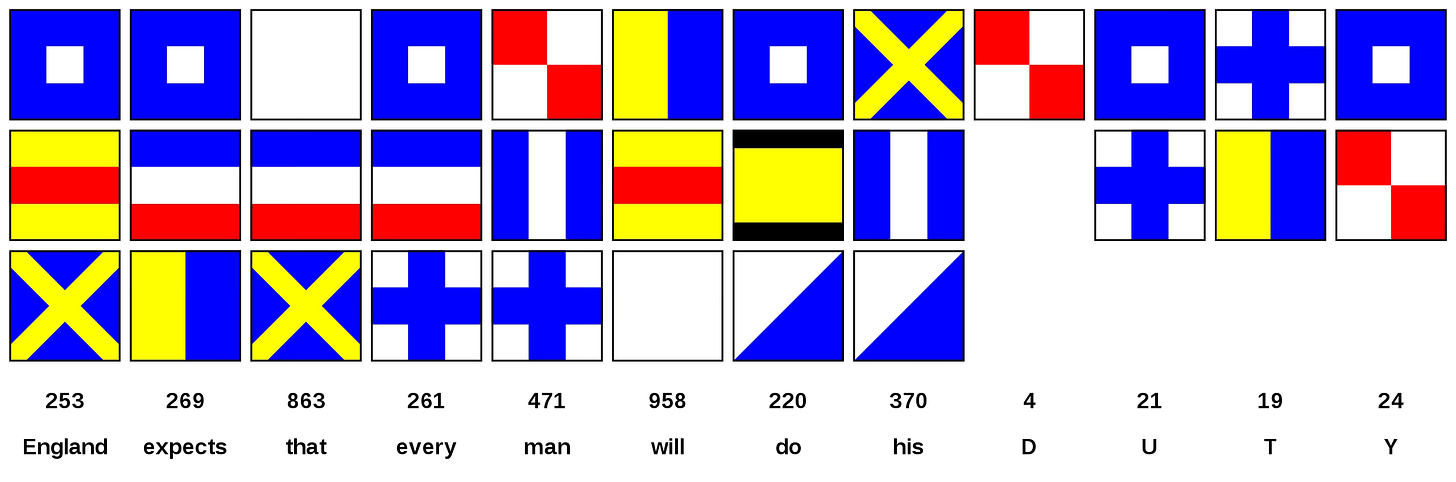

At one point, he instructed his signal officer, John Pasco, to hoist flags bearing to the fleet the message: England confides that every man will do his duty. While most of these words have standard renderings in semaphore, there was no standard flag for either of the words confides or duty. Pasco first suggested changing confides into expects, for which a flag combo was available, which Nelson agreed to; the word duty was simply spelled out using individual letter combinations. Here’s how the message eventually looked (hoisted on HMS Victory’s mizzen in 12 separate lifts):

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/

By the by, one wonders why Pasco didn’t suggest rephrasing it as England expects every man to do his D U T Y, which involves only 11 lifts, or Do your D U T Y for England (eight lifts), or even Just do it (three; maybe adding ye lubbers!), which would’ve allowed him to get on with Engage the enemy at closer range more quickly, in this slow-motion sea battle.

To confide means to place trust in another. Nowadays, it’s rarely used in the way Nelson wanted to. Instead it’s used to indicate a person whom one regards as a confidant: to confide in somebody. In the subclause construction here, we’d more likely say to trust, and, whereas trust is a unilateral declaration that can be well-founded or mistaken, it’s clear that any act disappointing the trust placed in someone else dashes the expectation of them who place the trust. Thus do confide, trust and expect all come to mean the same thing whilst not actually, in and of themselves, imposing any obligation on those at whom the message is directed. The message was not England orders …, or commands, or You must.

How do you reckon the message was received? Was it inspirational? “Couldn’t have put it better myself!”? Or was it closer to flogging a dead horse? “Bleedin’ ’ell, leave it out, mate!”?

Nelson would be killed in the heat of the struggle, and his body was returned for interment in London’s St Paul’s Cathedral in a barrel of brandy. The first of the many memorials to be erected in honour of the victory at Trafalgar and of the lamented commander was put up in 1805 itself in no lesser a locality than Taynuilt, as much a place in the middle of nowhere as any Highland Scottish town could lay claim to being. This is less surprising if one knows that, in fact, whatever England confided or expected, as the case may be, nearly a third of the British crews at Trafalgar and five of the fleet’s captains didn’t come from England at all. They hailed from Scotland.

A goodly portion came from Ireland, as well, which is why Dublin, too, had its very own Nelson Pillar, at least until it was removed in 1966, ’tis thought, by the IRA.

As they came to the crossroads, she turned to look down the length of O’Connell Street and saw the tall Doric column that stood halfway along with the statue standing proudly on the plinth, its nose in the air so it didn’t have to inhale the stink of the people it lorded over.

“Is that Nelson’s Pillar?” she asked, pointing towards it, and both Smoot and Sean looked around.

“It is,” said Smoot.

“It’s a fine thing, isn’t it?”

“It’s a load of old stones thrown up to celebrate the Brits winning another battle,” said Smoot, ignoring her sarcasm. “They should send the bastard back to where he came from, if you ask me. It’s been more than twenty years since we achieved independence and still we have a dead man from Norfolk looking down over us, watching our every move.”

“I think he adds a certain splendour to the place,” she said, more to annoy him than anything else.

“Do you now?”

“I do.”

“Good luck to you so.”

From The Heart’s Invisible Furies, by John Boyne

Semaphore is a type of code. If you cannot decipher what Nelson’s flags mean, you won’t understand the message. The message was intended to encourage the sailors to fight valiantly. It was an attempt to influence their conduct. To that extent, the “England expects” message is a code of conduct. It issues no commands, and yet it does. A code of conduct sets down what is expected. And the implication is that, if what is expected is not delivered, disciplinary proceedings will ensue. But not always.

The senator for Rhode Island, Sheldon Whitehouse, has welcomed the adoption by the bench of the Supreme Court of the United States of a code of conduct. It’s never had one. Now it does, although it’s not as though it was adopted in some orgy of avid enthusiasm for the principle of accountability. More or less, it comes as the result of assiduous reporting and revelations by ProPublica concerning alleged abuses of privilege and position and of influence-peddling concerning Clarence Thomas, Sam Alito and possibly others (see my articles here and here and here).

So, that’s that. There’s a code of conduct and ProPublica won. Whoopee. Of course, Mr Whitehouse does go on to point out that there is no enforcement mechanism to this code of conduct. Which means, what, exactly? Well, if the justices flout their code, no doubt voices will be raised, assuming they’re caught doing so. But they’ll not be disciplined, because they can’t be. There is no legal means to remove a Supreme Court justice. As John Grisham’s novel The Pelican Brief amply illustrated, such means exist—even outside the confines of a novel—only in the de facto world, but not the de iure one.

The power and compulsion of Nelson’s message to his sailors on the day of the Battle of Trafalgar held greater sway and were more exacting in terms of compliance than the code of conduct introduced for the Supreme Court of the United States.

I just thought I’d flag that.