Denmark has lost ... its post office

No letter today

Last week, I was working in the shop where I work. As you do. And the buyer, who also owns the joint and is a friend of over ten years’ standing, waved and caught my eye as she was about to disappear through a door, and called out, “’Bye. I’m leaving now.”

I raised a hand of acknowledgement and called back, “Do write. Send postcards, will you?” She laughed, said, “Sure, but I’m not going that bloody far,” and disappeared through the door. Well, one thing’s for certain: she wasn’t headed for Denmark, then. For, on 30 December 2025, Denmark stopped its postal service. So, I guess there will never again be a post card from that salty old queen of the sea. By which, of course, I mean wonderful, wonderful Copenhagen.

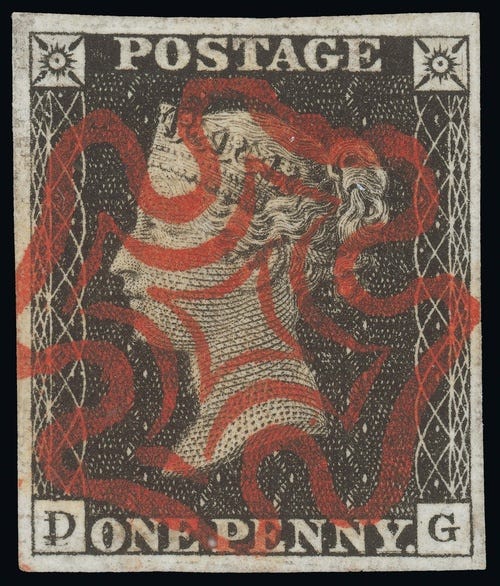

The first national postal service for any nation’s people was Britain’s. It was instituted by Sir Rowland Hill in 1840 and was known as the (uniform) penny post. For one penny, anyone could purchase a Penny Black postage stamp, stick it to a letter (the very first ones needed a pot of glue) and have it delivered to anyone, anywhere in the kingdom. That was revolutionary, because until then the conveyance of letters had depended on the number of sheets you wrote (early posted letters were often written in two directions, to save paper) and the distance you were sending them. They were paid for by the recipient, and not the sender, so that the whole operation was in vain if the addressee simply refused to accept the delivery. It was the advent of the railways (after 1830) that led Sir Rowland to his idea, since trains could distribute mail much more efficiently than mail coaches. Soon mail trains and mail packets (steam ships) were instituted to connect all parts of the kingdom and, ultimately, with the inception of the Universal Postal Union (UPU) in 1874, the British empire (and, indeed, the few bits of the world that weren’t the British empire). There is something tangibly wonderful about a postal packet that has physically crossed vast distances by seagoing vessel or aeroplane, dispatched by a real individual, to be received by a real individual.

Image: this 1840 penny black, with Maltese Cross post mark, sold at auction for £450.

The terms of the charter of the UPU provide that countries convey all mail received from other countries free of charge, on a reciprocal basis, so I assume the Danish decision now means they are no longer a member of the UPU and therefore it is no longer possible to send letters to that country, though I await clarification on that.

The railways leading to Holyhead on the island of Anglesey, and to Portpatrick on the west Scottish coast were built with the sole intention of carrying the mails across to Ireland (then an integral part of the UK). Portpatrick proved awkward, with a 1:50 descent to the harbour from Dunskey Castle atop the cliffs above the town (both of which can be seen at the tail end of the 1952 film Hunted, with Dirk Bogarde). Hence it was soon decided that Stranraer should take over from it, situated as that port is on the more sheltered shores of Loch Ryan, to serve Belfast and Larne. Holyhead served, and still serves, Dublin and Dun Laoghaire.

This past Christmas I resumed my old practice of sending out Christmas cards. I have no account with social media any more, nor do I have a mobile phone so, I reasoned, if I am to retreat into the late 20th century, then I must resort to the practices of the late 20th century. Writing the cards was time-consuming, posting them was expensive, and the whole procedure really was tremendous fun, each one of them with a small personal message written on the inside. I truly felt it was worth it in the end: the greetings I sent entailed some work, and therefore, I hoped, they’d be as valued as the greetings I also received in the post in return from family and friends. When we introduce friction back into our lives, which technology has now made so frictionless, I would hope that that reaffirms in our own minds the importance of the relationship that we are servicing, in this case by sending a card or a letter; hopefully it reaffirms its importance also to the recipient (especially as, nowadays, they don’t need to fork out for the privilege of receiving it).

My old school wrote to me recently and asked if I’d be interested in corresponding with a current member of the school’s population, in an exchange of experiences and as a sort of Dutch uncle. Of course, I readily agreed and have exchanged letters with a young chap aged 12 who has just started at the senior school. At the request of the organiser of this project, I hand-wrote the letter, then scanned it and sent it by e-mail to her for forwarding. It was the first time in yonks that I had hand-written anything more than a shopping list or a note to my house mate to put the rubbish out, please. The first major task was to find a pen that actually still wrote. Then to find suitable paper (A4 is not for personal letters). And finally, I needed to keep shaking my hand as cramps started to set in. Writing: an exercise I used to do from morning to night without problem. And now, one letter is a challenge.

A chap called Willy came over a few days ago to see me. Several weeks back, he had popped little sheets of paper with his name and phone number into the letterboxes up and down the road where I live asking if anyone had any foreign coins sitting around that they’re not doing anything with, which made me laugh, as I don’t often see a need for groschens and forints in my daily grind here. So, with an accumulation of coins from my touring travels, and a few other coins of interest (well, big size), I thought he might be interested.

“Most of this is fairly standard, Mr Vincent,” he said. “At the club, we generally exchange this sort of stuff for about four euros …” “Oh!” I interjected. He continued: “… per kilo.” “Of course,” I said. I didn’t want to appear like some novice, novice and all as I was appearing. But he identified an Isle of Man commemorative crown and a blackened one dollar coin from 1890, which had a frame around it to be worn as a medallion and which a tourist from the States had once gifted to me, and said that each of these was worth about 25 euros, so he offered me 60 euros for the job lot that was housed in my ancient cash box. I readily agreed, thinking it very fair and honest. “I would rather like to keep the cash box, however,” I said: it had belonged to my great aunt, when she ran the refectory kitchens at Nottingham University in the 1920s, so it had great sentimental value. Willy declared himself perfectly happy with a freezer bag instead.

In our conversation, I mentioned that I had previously been an avid collector of postage stamps, and we reminisced about the Rue du Midi, the street in Brussels which had as recently as the 1990s bustled with stamp dealers for practically its entire length. “Nobody collects them these days,” he said. “General collections are as good as worthless—you can’t even give them away.” I disagreed with him: a few years ago an old friend gifted me his own collection, and I love it. For Willy, each coin has a character and a history. For me, each postage stamp is a work of art, is trying to say something in the space of a few square centimetres, something cultural, something political, something celebratory, something artistic, something that tells a story. I have albums of first day covers and full sheets of stamps and some with markings almost indecipherable to the average eye, but which mean instant recognition for us philatelists. Of course, Sir Rowland Hill secured one privilege for Britain’s stamps: as long as they bear the head of the sovereign, they are the only stamps in the world that do not proclaim their country of origin in word form.

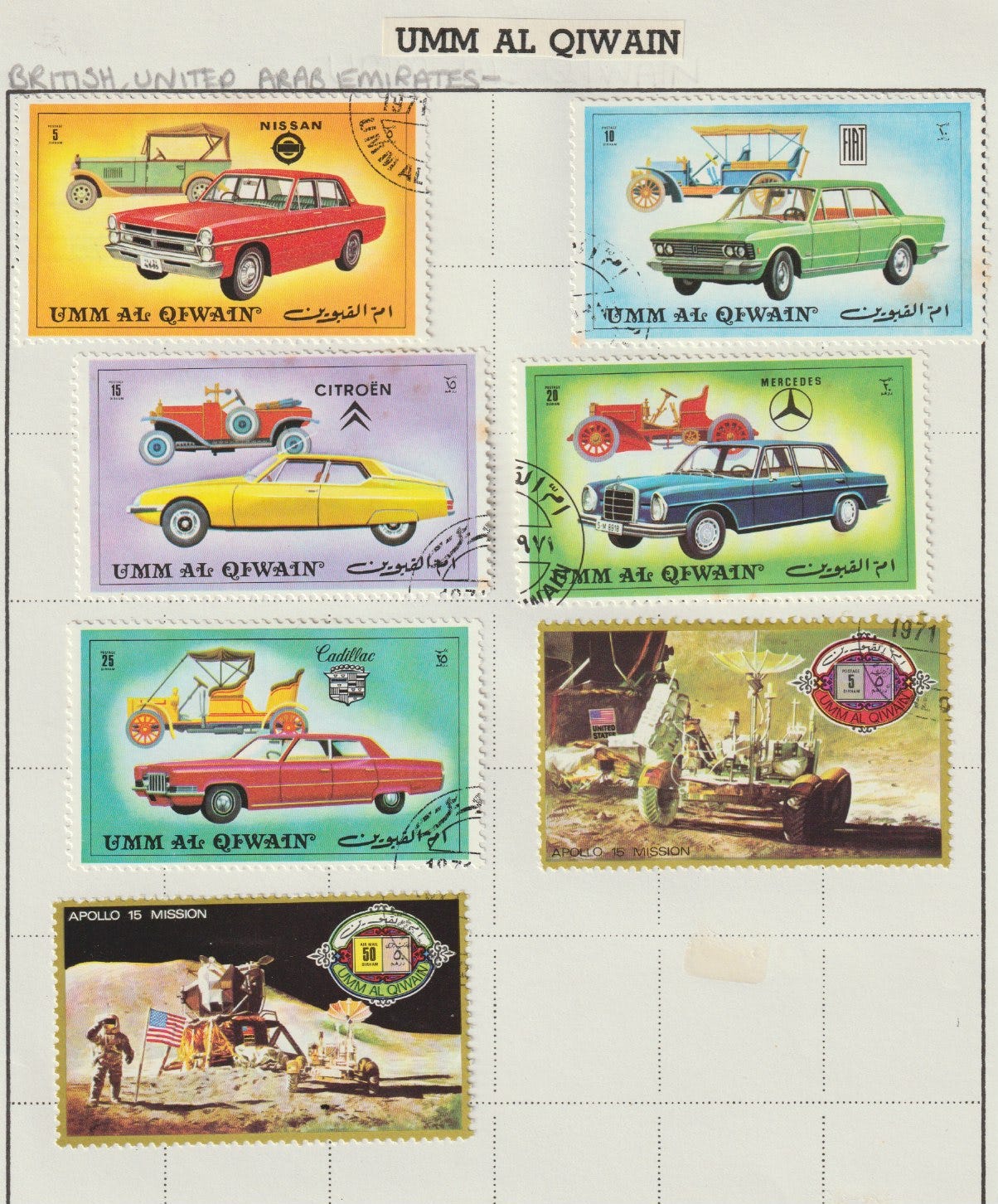

One small curiosity in my collection was always the vast quantities of gummed stamps that could be acquired from a group of countries known at the time as the Trucial States, now the United Arab Emirates. These tiny sheikdoms would issue reams of gummed stamps that postal traffic in their home market could never have justified. They would be cancelled to order (i.e. postmarked immediately after being printed) and had therefore never once seen the face of an envelope. They celebrated moon landings and birds of the world and no end of colourful subjects, and were a delight to children, whilst receiving scant respect from serious collectors. But without them, I’d never have known about Sharjah, Ajman, Umm Al Qiwain, Fujairah, Ras Al Khaimah, and Qatar (which friends and I called Quarter). For my sins, I captained the schools Stamp Club for several years, before ‘O’-levels assumed their rightful importance in my scheduling. But we loved these little works of art, exchanged them, talked about them, and collected them.

Finally, for any of you out there who ever collected Danish stamps, one benefit will come out of the demise of their post office: you can now have an absolutely full, complete set of Denmark stamps. And that is a world first.

Image: from my stamp album, the page for Umm Al Qiwain. Printed and issued simply for the collectors’ market, but a valued source of revenue for the issuing authority at the time.

I sent a Christmas postcard to Dublin last month. It cost eur 7.8 and took three weeks to arrive. I wonder if Belgium is phasing out its postal service?

What is suitable paper for personal letters?