I never knew what a homecoming queen was. All this time, I’d imagined it was something like Elizabeth II taking the plane home from some Pacific island. Rather, I couldn’t imagine it being anything but that, except it’s a term that trips off Davy Jones’s tongue so naturally in the song Daydream Believer.

I decided to root for an answer, and I got one. The first Homecoming occurred in 1911 in Missouri and comprised a football game (American rules) between the Missouri Tigers and the Kansas Jayhawks. These two teams had developed a rivalry that became known as the Border Wars and, to ensure the peace, had till 1911 played each other on a neutral pitch in Kansas City (in Missouri, of course).

When a new rule came in requiring college football teams to play on college premises, the peace treaty was cast to the wind, and the teams’ 1911 fixture was set for the home team’s grounds in Columbia, Missouri. In order to whip up the rivalry that had hitherto been partly laid to rest by the choice of a neutral ground, the athletics director sent out letters to former students inviting them to return home to witness this new, ebullient expression of college partisanship.

From there, homecoming expanded way beyond the rabble-rousing reunion it started as. My own school in England has what it calls an Old Grovians’ Autumn Reunion, at which there is a rugby game between the school’s First XV and an Old Grovians (or former pupils) fifteen. I suppose you could equate the two of sorts, but we never had homecoming queens (or kings, for that matter) at our school, who are not, it must be said, former pupils but are generally pupils in their final year of study, who are marked out as exemplary members of the school’s community—it says ’ere. The girl who attains this coveted accolade is therefore known as a Homecoming Queen, and she may reign over a whole court of princes, princesses and even an aristocracy of dukes and duchesses. My years of confusion stemmed from my thinking the queen is coming home; no, she is the queen of the event known as a homecoming; thus must one read the phrase.

Despite having rid themselves of royalty, the Americans never lost their fascination for it (a trait they have in common with the Germans). If Americans wonder at me for being so ignorant about homecoming, the sources I referred to note that it is widespread in the US, Canada and Liberia. Not exactly everywhere.

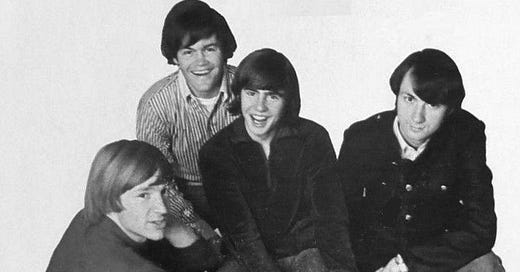

The Monkees are recognised as the first boy band (the result of being composed, rather than organically growing together), although Davy Jones, Mike Nesmith, Peter Tork and Micky Dolenz were indeed all musicians in their own right (rather than singing talent show contestants). But the production behind them was an entire industry: they had their own TV show, their own Monkee-mobile car (à la Batman), and they had good writers and managers behind them. They even had internationality—three Americans and a Mancunian. (I wonder whether they knew what homecoming queens were back in Manchester in the day. If parochialism is a lack of awareness of the customs of others, is patriotism simply a disregard for the customs of others?)

In the text that follows, Chip was the record producer, Chip Douglas. Seven-A was the take, one of many for this song, to Jones’s clear disgruntlement (odd that this aside (a) made its way onto the master cut and (b) is even cited word-for-word by lyrics websites—compare the phone ringing at the end of David Bowie’s Life on Mars). Now you know how happy I can be was inserted at the record label’s insistence: they didn’t like the word funky, because it means smelly. That’s what they said, at least. Later cover versions repeated the change to happy, even though it contributes nothing to the song—quite the contrary. Sleepy Jean is supposed to be a personification of youthful ambition, but I think that’s reading too much into it. Without dollar one sounds very odd: even if it were French, the one would come before the currency. Anyway, the message is clear: white knights on steeds need no dollars to be funky. I had always thought Jones sings that his shaving razor stinks, which I suppose would fit with him being funky. But it stings (listen carefully, however). What other kinds of razors exist that are not for shaving, I do wonder? The piano introduction was added by Peter Tork, and the seven-note lead into the chorus started life two years previously in the Beach Boys’ Help Me, Rhonda (unless some archaelogist can predate it even further; like the second part of The Killing of Georgie by Rod Stewart (Oh, Georgie, stay, don’t go away) which was, knowingly or otherwise, calqued from the Beatles’ Don’t Let Me Down—John Lennon said he thought the lawyers must’ve missed that one, and I think he was right).

The Monkees did a number of revivals in later years, and their fanbase stayed faithful, even though the group’s main success covered just four years. Three of the guys are now gone from us, and only Mickey Dolenz remains. The right-handed, left-footed drummer: a set-up dictated by a childhood disease.

It almost becomes a chant, as we sing along to those two lines: what can it mean to a daydream believer and a homecoming queen? What’s not answered is what can what mean? The link is to the single as cut, not the oft-seen tomfoolery performance. Well, you do want the intro, don’t you?

Daydream Believer

Written by John Stewart

Performed by The Monkees

From their 1968 album The Birds, The Bees & The Monkees