This post can be listened to as a eulogy by clicking above.

When my aunt died in 2019, I felt a strong urge to be at her funeral, but funds were low and it seemed impractical. People do cross the world to attend weddings, but not many take a plane from Belgium to Toronto to be at a funeral.

I asked my brother if he’d lend me the fare, and he wisely counselled me to think again—weren’t flowers a tad more practical? But I told him a story he did not know, about how our side of the family had slighted the Canadian side of the family, and he immediately understood and said I should go, since it would repair a scission that had gone on too long, and which I felt a burning need to put right.

In the end, I stretched my credit card and didn’t need to borrow any funds from him, and off I went to Toronto, with less than a holiday feel to the trip.

Upon arrival there, the very first evening I was out at the front of the house and my cousin was chatting to neighbours. She beckoned and I sauntered over to say hello. I was immediately presented with an envelope. What could this be? I looked inside. Canadian bank notes to a value of 790 dollars. For me. To help me with the costs of coming, from the neighbours. Not asked, but a whip-round at their own initiative. I was bowled over, speechless, pinching myself. And grateful. I said, “Thank you.” It seemed nothing less than bizarre: a nephew flies to Canada for his aunt’s funeral and neighbours spontaneously present him with the cash to cover his air fare. How probable is that?

I stayed with my widowed uncle and his grandson (my cousin once removed) in the home my aunt and uncle had bought back when they were founding their family. I’d stayed in it a couple of times before, in 1985, in 2010, in 2016 and now, for the fourth time, in 2019. Before that, I had met my aunt when they visited England in 1969, and at my parents’ golden wedding dinner, in 2002. I met her six times. You might say I barely knew her.

In the few days until the actual funeral, I made myself what I thought would be useful, by tidying up the garden and such like. My uncle was a devotee of the visual arts: painting, wood-carving, photography, sculpture, but had been devastated in later life to have as good as lost his sense of vision. He wore “ashtrays” and used magnifiers to read his Toronto Sun newspaper. I saw that a garden hose had been left out and was concerned that he could easily trip over it, so I rolled it up and tidied it into a lean-to cupboard where things were somewhat safer.

Well, he gave me a right rollicking for doing that, and put my back up a bit. It had been a dirty and far from easy exercise to roll up this garden hose, and all he could say was, “Why don’t you mind you own business?” Indeed, why hadn’t I?

I laugh now as I recount this daft episode, but I barked back at him, “Bill, you have chid me for the last time.” “I’ve what?” enquired he. I realised I’d used a Scotticism: “You’ve chided me for the last time.” And, as things transpired, that was true.

But truer would have been to say he’d chided me for the only time. For he was gentle, and sensitive, and approachable, and took an interest in all, and died alone in a sterile hospital during the pandemic, despite his family being only a mile away. And there’s an odd parallel there. For my father, his brother, from whose obituary all mention of Bill had for some inexplicable reason been omitted, thus giving myself good cause to wish the Earth would open up and swallow me, likewise had died alone in a sterile hospital. In spite of his family being only a mile away.

I had been asked if I wanted to say a few words at Peggy’s funeral. I’d agreed, and prepared a short speech. They say at Toastmasters that most people at a funeral would much sooner be in the casket than giving the eulogy. But I was a Toastmaster once and funerals hold no fear for me: not even my own. Before me went grandchildren and children of the departed. Last of all was my turn, just a tail-ender. I counted the heads in the room: 55.

I approached the lectern and said (I remember it verbatim), “Nobody in this room met Peggy Vincent less often than I did. And nobody in this room, including her husband and children, knew her better than I did.” An arrogant, audacious, dismissive, awful thing to say, and, to boot, intended to heal a rift. And heal it, it did. For it was true.

My cousins and my uncle and his painting friends and their circle of neighbours all knew Peggy much better than I did in terms of her history and her occupation and her hobbies and her shopping habits, of that there was no doubt. But elderly, married women sitting on porches and verandahs with curious, younger, gay men discuss things that never come up as topics between mothers and their offspring, or wives and their spouses. That knowledge.

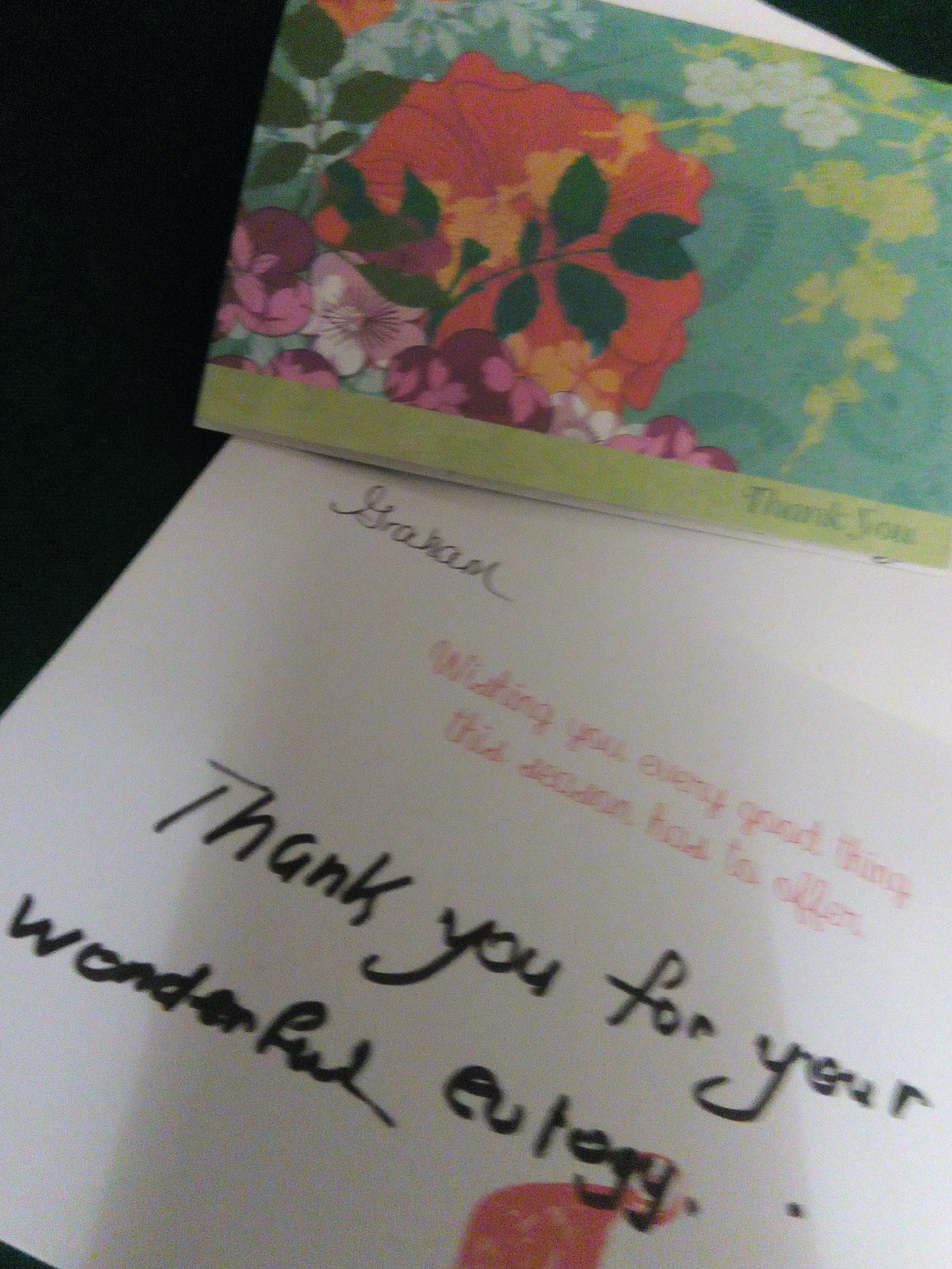

“Words cannot express our thanks for your presence at mum’s celebration of life and your eulogy. So many people enjoyed it—as did we,” wrote my cousin. The widowed uncle kept it simpler: “Thank you for your wonderful eulogy.”

I say there were 55 in the room at the funeral parlour. There were, of course, 56, besides me. Maybe even more. But I didn’t know it then. Now, I know.

The rift between the Canadian and British sides of the family had arisen during trips my parents made to North America. My mother has passed and I know she has no objection to my writing this, but she and Peggy were hewn from different stones. I cannot speak for Peggy, for it’s a matter in which I have no interest, but I can say that my own mother “infected” her sons with an aversion to Canada. She was wrong to do that, and she now knows it, and I am very pleased to now maintain close, placid relations with my folks over the Pond.

So, you may be asking, “What happened to convince me there were 56 people there?”

The evening before the funeral, I was alone in a gazebo erected by the back door of my aunt and uncle’s home, and, it being late August or early September (I cannot recall exactly which), it was still late light and pleasantly balmy in the evenings. I laid down a book I was reading and listened to the silence, which was presently broken by the rising chorus of cicade beetles, competing for the favours of females with whom to mate. The chorus rose, peaked and then ebbed again. I suppose that must mean one of them won his bride.

My thoughts drifted; I looked again at what I’d written as notes for the speech the next day and into my head popped a notion related to the cicades I’d just heard. I remembered having heard about locusts which ravage Africa in swarms of thousands, eating crops to stubble in minutes. Strange to think of that, for I don’t think I’d dwelt on the subject of locusts since I was in Geography class at school. As quickly as the notion popped into my head, it popped out again. It was time for dinner.

I’d not realised I would be giving a eulogy. I’d planned to say a few words of appreciation and ended up citing Shakespeare (the death speech of Warwick the Kingmaker in Henry VI, Part 3), the Bible (the passage I discuss in my article A Tale of Heads, which I’d also read at my own mother’s funeral—the only means I knew of to bring the two of them together in reconciliation), as well as citing myself: a Facebook post I’d put up about Jodie Foster, perhaps the most important of the three, because it came from me.

Ah, who is nigh? come to me, friend or foe,

And tell me who is victor, York or Warwick?

Why ask I that? my mangled body shows,

My blood, my want of strength, my sick heart shows,

That I must yield my body to the earth

And, by my fall, the conquest to my foe.

For who lived king, but I could dig his grave?

And who durst mine when Warwick bent his brow?

Lo, now my glory smear’d in dust and blood!

My parks, my walks, my manors that I had.

Even now forsake me, and of all my lands

Is nothing left me but my body’s length.

Why, what is pomp, rule, reign, but earth and dust?

And, live we how we can, yet die we must.

Mark 12:13

13 And they sent unto him certain of the Pharisees and of the Herodians, to catch him in his words.

14 And when they were come, they did say unto him, Master, we know that thou art true, and carest for no man: for thou regardest not the person of men, but teachest the way of God in truth: Is it lawful to give tribute to Caesar, or not?

15 Shall we give, or shall we not give? But he, knowing their hypocrisy, said unto them, Why tempt ye me? bring me a penny, that I may see it.

16 And they brought it. And he saith unto them, Whose is this image and superscription? And they said unto him, Caesar’s.

17 And Jesus answering said unto them, Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s. And they marvelled at him.

18 Then came unto him the Sadducees, which say there is no resurrection; and they asked him, saying,

19 Master, Moses wrote unto us, If a man’s brother die, and leave his wife behind him, and leave no children, that his brother should take his wife, and raise up seed unto his brother.

20 Now there were seven brethren: and the first took a wife, and dying left no seed.

21 And the second took her, and died, neither left he any seed: and the third likewise.

22 And the seven had her, and left no seed: last of all the woman died also.

23 In the resurrection therefore, when they shall rise, whose wife shall she be of them? for the seven had her to wife.

24 And Jesus answering said unto them, Do ye not therefore err, because ye know not the scriptures, neither the power of God?

25 For when they shall rise from the dead, they neither marry, nor are given in marriage; but are as the angels which are in heaven.

26 And as touching the dead, that they rise: have ye not read in the book of Moses, how in the bush God spake unto him, saying, I am the God of Abraham, and the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob?

27 He is not the God of the dead, but the God of the living: ye therefore do greatly err.

28 And one of the scribes came, and having heard them reasoning together, and perceiving that he had answered them well, asked him, Which is the first commandment of all?

29 And Jesus answered him, The first of all the commandments is, Hear, O Israel; The Lord our God is one Lord:

30 And thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind, and with all thy strength: this is the first commandment.

31 And the second is like, namely this, Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself. There is none other commandment greater than these.

32 And the scribe said unto him, Well, Master, thou hast said the truth: for there is one God; and there is none other but he:

33 And to love him with all the heart, and with all the understanding, and with all the soul, and with all the strength, and to love his neighbour as himself, is more than all whole burnt offerings and sacrifices.

34 And when Jesus saw that he answered discreetly, he said unto him, Thou art not far from the kingdom of God. And no man after that durst ask him any question.

Anyone remember the Jodie Foster film Contact? In it, Foster plays an astronomer detailed to scour the skies for signs of extraterrestrials. One day she finds them; they send her plans of a device that will allow her to travel to see them. It’s built and off she pops down a wormhole to greet ET on a beach somewhere beyond alpha centauri. She returns to Earth and makes her first mistake: she tells of her travels.

When people ask if I’m religious, I generally reply that I’m spiritual. Those who think that’s the same thing don’t know what to ask next. Those who know it’s not, know to ask no more.

Religion is a guided visit: a panoramic bus tour on which your group views a foreign place from the comfort of a padded seat, through a polished glass window.

If you buy the guidebook and ditch the guy with the umbrella, it’s possible to view that place without the polished window, but it’s less comfortable.

Spiritualists have no guidebook. They delve down alleys that can be hard to find a way out of and blunder across lines that in a museum are marked “do not touch”. And, when they return from a trip, they can tell no one of where they’ve been or what they’ve experienced. That much is learned from the movies.

Spiritualism, the partner of religion, which builds community, fellowship and togetherness, breeds isolation and, ultimately, cynicism from both spiritualist and non-spiritualist alike.

But, if not fact, it’s truth beyond what one can fathom.

After the ceremonial part, there was a light buffet and tea and coffee, and around the room were the gifted flowers and a number of large collages that had been prepared in years gone by to celebrate my aunt and uncle’s golden wedding and her whatever birthday. Many of the folk came up to me and were very kind with their thanks and appreciation and even handed over contact cards. After a while, I felt tired and asked to be excused and decided to take some minutes to wander around the hall on my own. Everyone crowded on the other side to admire the collages and flowers, but over in one corner of the room, lost somewhat, was a simple photo frame containing, not a photo but a sheet of paper with typewritten script on it. It drew me and I made my way over to read it.

I smiled. I remembered these things; I’d never had one myself, but I’d watched children’s TV programmes where they planted trees and buried one of these beneath them: a time capsule. This wasn’t a real capsule, but a record of the world when Peggy Vincent came into it. The prime minister was Richard (R. B.) Bennett (in Britain, it was Ramsay MacDonald); the king (in both countries) was George V; popular songs were Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?, How Deep Is the Ocean? and In a Shanty in Old Shanty Town, and, that day, all of those songs said something to me, having just tried to spot my bro’ for some cash to cross an ocean, from my shanty town to Canada. A miscellany of trivia of no great importance whatsoever, until my eye alighted upon the world’s news on the day that Peggy Vincent came into it: in Africa, a plague of locusts had ravaged crops from west coast to east.

Things like that just happen. I explain it this way: suppose you go to a railway station and there are telephone booths, but you have never heard of the telephone. How would a telephone company let you know what these devices are and what they are for?

By making them ring? Would you jump on a fire truck and shout, “Hello, who’s there?” There is no explanation, no manual, because there can’t be, for whatever reason. So, by what means would you discover that these are a means of communication?

Others might come up to you and say, “You can use this to speak to someone far away.” But others might come and say, “That’s nonsense, I’ve tried it, but there’s no one at the other end of the line.” And still others might come and say, “Yes, but you have to do the speaking; he can’t speak to you, but he can show that he is there in other ways.”

If you’re to communicate, you have to know that there is a means to do so and then it’s helpful if you know how to operate it. But first, you have to know it’s a means of communication—a telephone, to speak to someone far away. That way, you’ll know that burning bushes are not just bushes that are on fire.