I reckon I am immune to advertising. I have a limited pocketbook and limited pocketbooks are a good means of being immune to advertising. The seductive ooh, that looks nice that reverberates at the back of my mind as I see something looking nice and seducing me used to be swiftly followed by a reverberated I have no money. Nowadays, it’s less that I have no money and more that the advertising is quite simply trying too hard. If buying two to get one free means the seller is still making a profit, then his profit is too large in the first place: buy two, get one free is tantamount to yelling but I stiff you the rest of the time.

They say that there have been huge shifts in advertising, which is a sector in which the mystery writer Dorothy L. Sayers was once active (she wrote a novel about it called Murder Must Advertise). Here’s what she said about advertising:

Of course, there is some truth in advertising. There’s yeast in bread, but you can’t make bread with yeast alone. Truth in advertising is like leaven,1 which a woman hid in three measures of meal. It provides a suitable quantity of gas, with which to blow out a mass of crude misrepresentation into a form that the public can swallow.

Nowadays advertising is predominantly online, and you can pay to opt out of it or block it, whereby advertising media will plague you with pleas to turn the advertising back on, even morally blackmailing you with lines like but we need you to look at the advertising in order to even exist (if you’re interested, I have an—entirely legal—means to enjoy most of YouTube ad-free without paying: just DM me).

We even have Elon Musk, the CEO of X, saying unspeakable things about advertisers threatening to withdraw their custom from his website (they want to bribe me? With money?); well, with what else, Mr Musk? Isn’t it money that’s used to bribe everyone (even with buy two, get one free), or perhaps he’d be an easier bribery target with … his sex life? criminal record? draft dodging?

Some things are good for us, and ought to be advertised. Governments call this public service information; we call it propaganda. The proportion of propaganda that is true is probably about the same as is true of advertising by the standards of Dorothy Leigh Sayers.

Here’s a clip from the Woody Allen film Sleeper. Woody went into hospital in 1973 for an ulcer operation, got deep frozen and has been woken up in the year 2173, where it is revealed to him that old conceptions of health have been overtaken by scientific discovery: wheatgerm is bad for you, and there’s nothing healthier than hot fudge and smoking.

The most we can say about what’s good for you and what’s bad for you is that there are received wisdoms about which is which, and we all decide in how far these apply (a) to us and (b) to everyone else.

For instance, smokers tolerate other people smoking. They tolerate being expelled outside in rain and freezing temperatures to indulge their habit. They tolerate paying £20 for a packet of cigarettes. They tolerate health warnings on the packets and the fact all packages are now drab green. They tolerate being fined 200 euros for dropping a tab end in the street. They tolerate the dangers of lung cancer. That level of tolerance is fairly impressive. If everyone were that tolerant, my, what a tolerant world we would live in. Smokers can leave their desks and pop outside their office for ten minutes to have a smoke, in most places. But if non-smokers got up and went with them and just stood around chatting for ten minutes, leaving the office bare of personnel, that might provoke comment. But, if smokers can abandon their posts for ten minutes, why can’t everyone?

Smoking is so reprehensible (except in the year 2173) that great amounts of legislation have been passed to restrict it, to ban it, to make it punishable, and yet people still smoke. Often, those who can least afford it and, by the same token, those who have least to lose from the negative effects of doing so.

In the US, smoking is most prevalent among

low-income

men

aged 45 to 64

non-Hispanic but not white, black or Asian

holding a general education development certificate as their highest level of education (lower than high school graduation)

divorced, separated or widowed

living in the Mid-west (especially Arkansas, Kentucky and West Virginia)

of LGB sexual proclivity

with a disability

insured by Medicaid

suffering feelings of severe psychological distress

who have ever been told by a healthcare provider that they had depression

(Data source here.)

Yes, they’re all bad for you. Even the Hobnobs. I heard a commentator who was involved in Coca-Cola’s bid to get Coke included as an eligible product for food stamps say that feeding a child sugar, processed grains and canola oil is more cruel than feeding it cocaine.

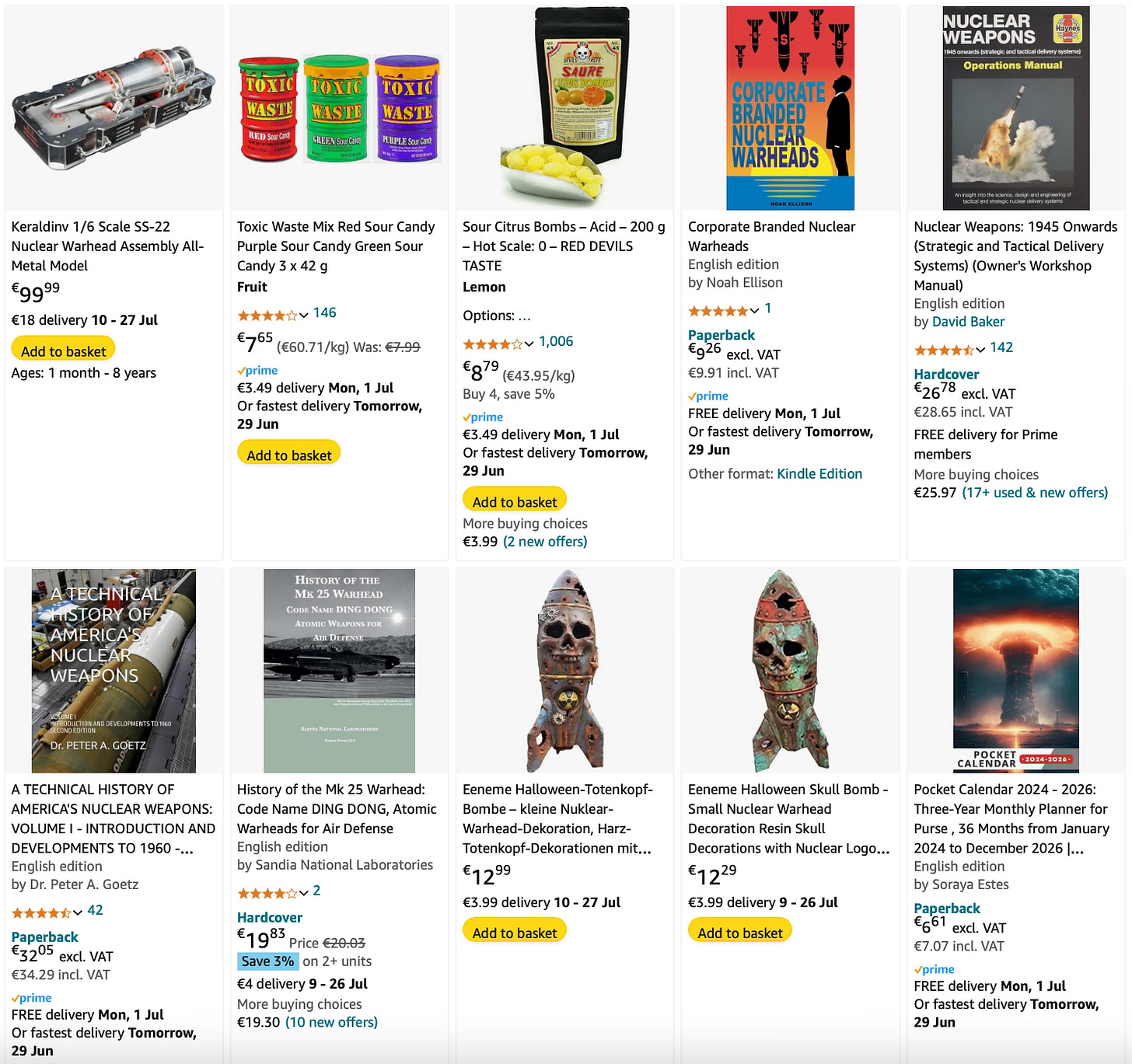

Now, a similar controversy is emerging concerning UPFs: ultra-processed foods. Take a range of products access to which is regulated (amphetamine, cigarettes, nuclear warheads, revolvers) and consider them in relation to UPFs. Access to amphetamine is restricted out of concerns, I presume, of public safety. Whether the public is safer having ruthless gangs of criminals operating worldwide to process, import, export and sell drugs that governments make illegal for considerations of public safety than if they just legalised the stuff is another controversy. You can buy cigarettes (if you’re of the minimum age) and smoke them (wherever it’s not prohibited) quite legally. Peripheral dangers, aside from those to the health of smokers and those around them, include causing house fires, wildfires (it probably caused the Mont Blanc tunnel fire in 1999), and one might also, as with amphetamine, consider the more widespread dangers that tobacco companies pose to society at large. Nuclear warheads are not generally available to members of the public, although operating manuals and nuclear-warhead-related products, like books, table lamps, candy and 1:6 models (suitable for kids aged 1 month to 8 years) did come up when I launched a product search on Amazon.

Guns don’t kill people. People kill people. And cigarettes don’t kill people, either. Not until they’re smoked. Amphetamines don’t kill people, until they’re snorted, nuclear warheads don’t kill people until they’re fired. UPFs are benign until they’re eaten.

UPFs are a different kettle of fish. Aside from the fruit and veg you buy straight off the market, everything else in a supermarket is classed as one of four types of processed food: minimally processed food, processed culinary ingredients, processed food, and ultra-processed food.

UPFs cover things like packaged baked goods and snacks, fizzy drinks, cereals, and ready-to-eat or ready meals. They go through multiple industrial processes and often contain colouring, emulsifiers, artificial flavours and other additives to aid preservation and presentation. They tend to be high in added sugar, fat and salt. They are the kinds of foods that often get disposed of at the end of their shelf life through food bank programmes designed to reduce waste and give a leg-up to the poor, like TooGoodToGo. One manufacturer of soft drinks with a high sugar content has successfully lobbied the US government to allow its products to be bought with food stamps. UPFs never look like the photo on the outer packaging: they’re very much presented on the outside different to what they in fact are on the inside. On the whole, we eat too much of them. The question is: are they so bad for us that they should be banned?

Well, UPFs are certainly not as big a problem as tobacco, and certainly not as much of a problem as purchasing a nuclear warhead could be. Concerns have been raised, with some scientists advocating the introduction of government health warnings, like on cigarette packets, and others pointing out that you cannot compare UPFs to tobacco, because tobacco is unquestionably bad for you (contrary to Woody Allen’s vision of the future), whereas UPFs contain stuff that is actually nutritional; the problem is simply that we eat too much of them.

A doctor ought to be able to say to a type I or II diabetic, or a drug addict, or a person with sclerosis of the liver, or a person with cardiac issues, or someone with high cholesterol or any number of other common ailments what that patient should or should not eat; what they ought to eat in careful measure, what they can eat to their heart’s content. Surely the diagnosis of an individual’s ailments cannot be so narrowly defined as to render any general advice inappropriate. One should be able to say that diabetics should not eat this or that, or at least diabetics should seek advice from their doctor before eating this or that. And giving that kind of information the same prominence on a UPF as is given to health warnings on cigarette packets should not then be objectionable.

I went and looked, for the very first time in my life, at a website of a gambling organisation. I don’t know who they are, but I looked on the opening web page for the warnings advising me of the danger of gambling addition. I regret to say that I found no such warnings. I was repeatedly pestered to sign up before I had even had a chance to read their terms and conditions. I took some screenshots:

It doesn’t say who the review is by, but I suspect it’s from their own pen. The opening home page borders on the predatory; it certainly issued no warning at this stage about addiction, and I suspect I would need to tell them all the contact details via which they could persuade me to enter their world of entertainment before they would so much as breathe the word. It’s not conclusive or scientific, but it leaves an impression.

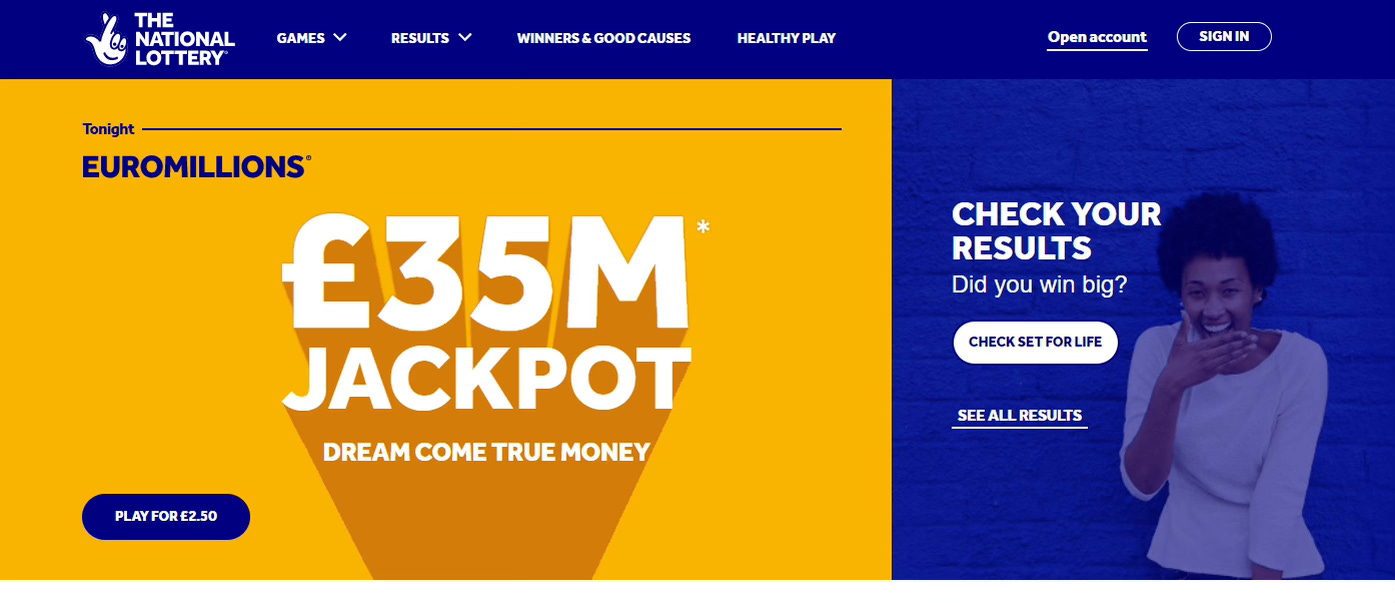

I often wonder whether there would be more, or less, gambling addiction if the warning against addiction and the prospects of winning were printed in each other’s fonts and sizes. How would it be if the words Healthy Play (see if you can find them) and £35 M* JACKPOT were to be written in exactly each other’s typefaces?

How would it be if manufacturers of UPFs were forbidden from festooning their packaging with pictures that are manipulated, colour-enhanced, food that is smothered in varnishes and chemicals to improve their photogenic allure? Serving suggestions designed to tempt the purchase? Is the product itself not temptation enough? What about one my pal and I recently had: all the ingredients you need for a chicken curry, in one simple box. Just add chicken. Just add what? How can it be a kit for chicken curry without any chicken—surely it’s just a kit for curry?

Now, the curry kit wasn’t UPF, but it’s indicative of the kinds of lengths that makers of retail produce will go to in order to edge the wool over the customer’s eyes. If UPFs bore a list of their ingredients and a list of the things in there that you need to be careful of if you’re diabetic, have a heart condition or tend to obesity, then that would flag the dangers for probably about half the people who buy those products who would be advised not to do so by their GP.

Doing so might well militate against the interests of the healthcare professions and drug companies, just as prohibiting members of the general public from acquiring nuclear warheads impinges on the profit margins of defence contractors (although there could well be an underground market in such things, as there is in AK-47s and other, equally frightening weaponry, some of it straight from the Ukrainian battlefield).

I’m not sure in how far UPFs can be compared to amphetamine; I believe the drug was invented in Japan to keep military fighter pilots awake at the controls of their aeroplanes, and anyone who’s given a Mars bar and a can of Coke to a ten-year-old kid at 11 pm will know that the effects of the two products on the two individuals is roughly the same. Armed forces have tended to be nonchalant as to the long-term effects of drugs they administer to military operatives. I think that confectionery manufacturers have probably had similar levels of concern for ten-year-olds, their blood sugar levels, their teeth, the hyperactivity and their tendency towards diabetes, overweight and the likes. Some believe the national interest outweighs the interests of fighter pilots in their personal health. And some believe that ten-year-old children don’t need to make informed dietary choices.

Perhaps the answer doesn’t lie in surgeon generals’ warnings, nutritional information or propaganda and manipulative advertising, because, with all the advertising standards that we have, nothing seems to protect the general populace from being inveigled into buying what’s bad for them, and we could save ourselves a lot of bother by just not restricting what goes into foodstuffs at all and leave it up to the individual’s judgment what they should ingest. That might inculcate a sense among people that they bear their own responsibility for what they consume, and how they behave.

In his 1970s BBC TV series Connections, James Burke takes us down on the farm. His first episode looks at the Niagara Falls relay failure that plunged New York City into darkness in 1965, and he asks how well the viewer would survive if that sort of thing were to happen on a widespread or permanent basis. Well, we’ve seen the films Independence Day and The Day After Tomorrow and The War of the Worlds, and the flight of city dwellers out into the countryside. But where are they all headed for? What happens to the rule of law when the rule of the mob and the fight for survival take over? And, even if you have no opposition, how do you battle Mother Nature?

Finally, somewhere far out in the country, you come across a place that looks right and let’s say that you’ve had the good sense and the good luck to look for a farm, because that’s where food comes from doesn’t it?

OK so it’s a farm, so you decide to stop: has anybody got there first, or are the owners still here? Because you’re going to need shelter, and people don’t give their homes away: they barricade themselves in.

So, sooner or later, exhausted and desperate, you may have to make the decision to give up and die, or to make somebody else give up and die, because they won’t accept you in their home voluntarily; and what, in your comfortable, urban life, has ever prepared you for that decision?

OK, let’s say by some miracle the place is empty and it’s all yours. Is there enough food in the house? How long will it last? How would you cook it? Are you fit enough to chop all the wood you need before winter comes? If you’re lucky you’ve got livestock on the farm: great, meat! But, can you slaughter and bleed and butcher an animal? OK, supposing you managed that, you’ve got enough meat to eat until you’ve eaten all the cows, but at least you can start running the farm.

But it’s a modern farm, remember: it’s mechanised. There’s a gasoline pump, but it’s empty, so you can’t use the tractor. What you need is a horse and cart, but when did you last see a horse and cart on a modern farm? And everything else here, the saw, the power drills, the light, the steriliser, the water supply, the sewage system, the hoist, the milking parlour, the pumps, and everything on this control panel demands the one thing you don’t have: electric power.

Everything on this farm that you found doesn’t work. The place is a trap. But there’s nowhere else to go. The only way you’re going to survive is if you find the one thing you need to keep on providing the food you gotta have, and you don’t need the mechanised version of that thing: you need the kind people haven’t used in 100 years. What you need is [shows it] that kind of plough.

You’re saved! Or are you? Because, what it comes down to at this point is this: can you use a plough? It’s taken a series of miracles just to get through this far and here you are: the biggest miracle of all, a plough, and animals to pull it. So, maybe after a few days of fumbling around with a harness and the bits and pieces, you manage to yoke up the oxen and plough the land; and then, and only then, can you say that you have successfully escaped the wreckage of technological civilisation, and lived off the land, and survived: if you know how to use the furrow you ploughed. I mean, can you tell the difference between an ear of corn and a geranium seed? Do you know when to sow whatever it is you think it is? Do you know when to harvest it, and eat the bit that you think isn’t poisonous?

I have little doubt that some of us would give up and die, because of our lack of knowledge of the things we need to survive in a world lacking electrical power. The question today is sooner, how many of us give up and die because of our lack of knowledge of things presented to us as necessities of life in a world that possesses electrical power? And, in today’s world, the rule of law is run on electrical power. Why else do you think Israel cut it off to Gaza?

What do you do if the rule of law itself, which is so dependent on technology for its functioning, is the very power source that the citizen wants to disable because it has become a source of malevolence, not benevolence? The Anonymous movement was a presence on the Internet that essentially hacked into establishment websites and caused a degree of havoc for them, using clever online technology skills. But, when the arrest warrant went out for Commander X, its putative leader, he fled to Canada from the US and ultimately decided to apply for asylum in Mexico. The problem was getting there, because the United States lies between Canada and Mexico. When you want to evade technology that you view as malevolent, you need to sneak over borders unnoticed, beneath the radar. Because you failed to take it down properly and its malevolence is now after you.

We are not simple tools to be used by manufacturers, but are masters of our own fate and must defend ourselves against those who would wittingly or unwittingly harm us. The problem with reliance on lawmakers is that we cannot place our entire reliance on them, and knowing where reliance is unwarranted, where the trusted party is duplicitous, is that bit easier if everyone is regarded as duplicitous.

In case you’re wondering, Sayers knew her Bible: the hiding of leaven is a parable cited in the Gospels of the New Testament. The Gospel writers actually compared leaven to the word of God, which is not what Sayers compares it to, even if advertisers do.