My motor mechanic is in Charleroi, which is 1½ hours’ drive away. In its time (the time being around 25 years), trudging the car down to the location of Belgium’s worst mining disaster (at Marcinelle in 1956: 262 deaths) has proved awkward: three or four of my friends have been prevailed upon over that time to help with getting me there, or getting me home. On this occasion, I reverted to an old expedient that I’d not used for a long time: a bicycle. Strapped to the back of my utilitarian Jeep, it’s easily unhitched and within a minute you’re mobile again, with half as many wheels to worry about.

No, I didn’t cycle from Charleroi to home, but to Charleroi main railway station. I asked the way a couple of times and got the responses that—and I guarantee it with my life—you always get in Charleroi, for its folk are among the friendliest and most obliging I know, and I asked eight people all told, none of whom sold me short on my expectations. It’s a huge pleasure to be lost in Charleroi (funnily enough, as on previous occasions, some mulled over the distance I needed to go: “C’est loiiin !” to which I replied with a smile, “C’est si loin qu’il est, mais heureusement j’ai un vélo.”)

On the way home on the train, which now departs from Charleroi Central (although all the road signs still direct you to Charleroi Sud, the station’s name until six months ago (do they not realise what changing a station’s name involves for all and sundry?)), I noticed graffiti out of the window, some of it really rather good. Banksy standard. Agora standard. The standard bearers of territorial claim; and of protest. One, upon exiting Brussels North station, was painted almost too well. Not tagged, but like a newspaper headline. I saw it again, at Haren. From afar, I read it as “SEXISTE”—French for sexist. Closer up, I realised what it actually said: “J’EXISTE”—I exist. And in that moment, I realised it may have been meant to be construed as both.

The ticket collector came by and I produced the five pieces of paperwork I had received for this single journey. She smiled and noted the two larger ones as being what interested her, approved them and handed them back. I asked her if she could punch them. Nobody, it seems, asks for tickets to be punched these days and she actually had a job setting the dials of her ticket-puncher in order to fulfil my request. She didn’t ask me why I wanted the tickets punched. But she did not refuse, because I have the right to insist that my ticket is punched. I told her of the Dorothy L. Sayers novel Five Red Herrings; no spoilers, but the whole solution to the murder mystery turns on the punching of railway tickets. The tickets punched in the novel proved that the traveller had been there. For, unpunched, my journey is virtual; punched, it is real. J’existe.

If Zaventem were to have been in Switzerland instead of Belgium, perhaps the railway station at the airport would have been called Aeroportus Zaventemensis (since it was Latin the Swiss opted for when naming their country Confœderatio Helvetica). Instead, it was for many a long year called Brussel Nationaal and, with other diminutive locations proclaiming themselves as host to an international airport, onlookers might be surprised to see Brussels proclaiming itself as merely national in function. But its official name was, or is, or whatever, Luchthaven Brussel-Nationaal or Aéroport National de Bruxelles for the other half.

Schaerbeek (the French and, usually, the default English spelling—cf. Ypres, Bruges, Louvain, Courtrai versus Ieper, Brugge, Leuven, Kortrijk), which I passed through on the train, is a borough of Brussels and is spelled that way because that’s how the Dutch spelled it long before Belgium was even a pipe dream. In the early 20th century, the Dutch decided, in collaboration with the Flemish, to reform some spellings of their language and the ae diphthong was supplanted by a double-a spelling, or done away with completely where the surrounding letters logically allowed of nothing except that elongated ah sound.

So, the Dutch changed the spelling of Schaerbeek to Schaarbeek. That’s okay, the Dutch can do what they please with their language. But the French language didn’t change, so the French continued to use the former Dutch spelling as the French spelling. That’s how sensitive language issues can get in this here land. I have friends living in the West-Flemish town of Geluveld and, when World War One was raging around the town, maps show it was spelled Gheeluveldt. So, the reforms saved quite a lot of ink.

But it is not feasible to use the word aéroport for the railway station at the airport of Brussels (which, when it was in Haren, was actually in Brussels but now, at Zaventem, is in Flanders (and is still considered too close to urban development)). That’s because it’s not in French- or bilingual territory. It’s in Dutch territory. So it’s a luchthaven (lucht: air; haven: port). You could call it an aeroportus (ah-eh-ro-port-us), which is Latin for airport (yes, Latin has words that post-date the fall of the Roman Empire), but, instead, the good folk of Zaventem along with Belgian Railways have plumped for the English word airport, as being as universal now as Latin once was. So, the station at the airport is called Zaventem Airport, which the shrewd will note is both Dutch and French.

And English.

And a bit German (technically Saawentem).

And quite a lot of languages. A Dutch-speaker will undoubtedly explain to me why Schaarbeek has two a’s and Zaventem has only one, and still has the same ah-pronunciation.

In short, the station that was once known as Brussel Luchthaven is now known as Zaventem Airport and the station serving the town of Zaventem is called Zaventem. But you don’t go through one to get to the other. Zaventem Airport is on a branch line that goes off the main line before you get to Zaventem. So you need to know which train you’re on.

In a bid to avoid weary travellers alighting at Zaventem only to find there is no airport there, the train announcements are now giving the town station the curious name of Zaventem Dorp (or Zaventem Village). When they recently placed a new flyover at Zaventem over the Brussels orbital motorway, there was traffic chaos for a day, even though it was a Sunday. Zaventem used to be the home of Suchard chocolate. It’s big. It has an airport. It is not a village by any means. And, when you alight at Zaventem Dorp, even the signs don’t say Zaventem Dorp. They say what they’ve always said—Zaventem.

With so much instruction now being automated and given by machines and inanimate or virtual means, why not just tell everyone what it will say on the signs when you get there, rather than wording everything with a sort-of subliminal Well, you know what we mean? Instead, we have pre-recorded voices announcing platform changes at Brussels South station, and sending all and sundry scurrying across the concourse, to the accompaniment of “We apologise for the inconvenience”—pre-recorded and meant as sincerely as Welcome to UK Border Control. Not quite a pleasure dome.

I exist. We exist. Staring out of a train carriage window, I sighed. And my gaze returned to the headlines in The Guardian, and the photo of Peter Tatchell leading a protest in England somewhere. Those around him wear teeshirts saying We exist.

Click pic for the article.

Well, there are precedents.

Charles IX, and Louis XIV, had laws against being protestant.

The United Netherlands had laws against being Mennonite.

They had taxes on the width of your staircase and we had taxes against putting in windows so we could see what we’re doing indoors.

The pope forbade railways because he viewed tunnels down the Apennines as promoting fornication. Or was the image of a long thin train disappearing into a dark hole in a hill just too scintillating for him?

St Paul decreed that all women in churches who don’t cover their heads are prostitutes.

And then being Jewish: being Jewish was outlawed across the Third German Empire and being Jewish was the law that brought Germany into Hell, since when it has luckily extricated itself. We think.

One common element to all these outrages is their antiquity. Except the latest iteration of man’s intolerance and hatred: being Ukrainian, likewise a sin that the holier-than-thou would seek to eradicate whilst orthodoxy blesses the yet unshaven, angelic faces of Russia’s youthful soldiers.

And that’s the moral of the story.

France can now be tolerant of protestants in its midst.

Holland can now be tolerant of anabaptists in their midst.

Germany has been able to show contrition, on its knees, if kneed be, for its hatred of Jewry in its midst.

And the popes’ hegemony from sea to sea is no more (he even has his own railway station now, accessible by tunnel, of course).

So, there is hope for Uganda and those in Uganda’s midst. It may yet repeal this law and re-enter the world stage of civilisation. But its gas is on a peep for now. The UN has protested, but the UN does not expel those who kiss the fringe of its cape, whilst enacting laws that are repugnant to the very notion of what our United Nations stand for. The UN admonishes because it has to; and is ignored by those it admonishes who feel like doing so.

Let us hope, campaign, and stop all aid. Right now. For we feed the Leviathan.

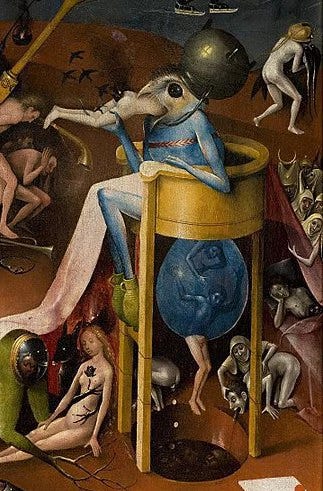

Image: The Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymus Bosch (detail). An anthropomorphic bird consumes sinners and excretes them into a cesspit, as another sinner excretes money into the same cesspit.