Click above to hear what’s below.

Translation in transition

In translation, there’s a tsunami of change underway. I’ve been talking to some colleagues and it’s a grim picture. Meanwhile, the Justice Minister resigned because his department of Justice is broken. Like my statuette of her.

A few years ago, in 2021, I phoned an old contact to ask if he’d work with me on revising a translation of the annual report of a bank. He’s a banking specialist. He as good as laughed at me: as if he would work for me!

I pressed him. I asked what he’d charge, because it’s ultimately about money. Minimum 20 to 25 cents a word. I work for nine and less and count myself lucky. Clearly, he’s a far better translator than I’ll ever be. But I wonder if now, in 2023, he’s still got a ream of clients paying 25 cents a word. He posted recently on LinkedIn: We all need to specialise. I recounted a bitter experience, from long ago: I laughed at him, but this time in bitter irony. And one of his contacts commented: You’ve obviously got the wrong clients. It was a lady, but I think, if she’d been within arm’s-length distance, I’d have slapped her smug face.

The Italian Job

A big translation firm in Italy contacted me out of the blue and presented me ultimately with the final irony. They had a very large document that had been translated by a machine (DeepL, it’s called). Could I ‘post-edit’ it? I could have started with their e-mail, but I don’t like to be rude:

Recently many clients apply this type of service as post-editing of AT texts in order maintain the budget and reduce the costs and delivery dates.

Please see here attached a sample of pretranslated text.

The rate for post editing of pretranslated text is Euro 0,0350 (note: taking into consideration new texts to arrive. The client has concluded a new contact so we expect many new texts to translate. That’s why we are looking for the translators to dedicate for this on going and future projects). [sic]

I was mildly amused that the price extends into the 10,000ths of a euro. Still, it looked good. A promise of a whole heap of future work. However, a caveat: if I had actually been given the whole heaps of future work that were ever promised to me, I’d be buried under Mount Everest by now. That said, hope springs eternal in the human breast.

You must understand that AI is how we now translate. We translate using what other people have already translated (because it’s so good) or what a machine thinks would be a good translation (so, we now have Europeanisms and Americanisms everywhere, because we are an ecumenical church). It can be quite a good method, but it holds dangers. A local food store here has to label British produce in Dutch. Their programming translated “still water” (no bubbles) as “nog steeds water”, or “hasn’t changed from being water” … it’s still water … (and mislabelling can result in an administrative fine for them).

And some people go bananas—En sommige mensen gaan voor bananen—Et certaines personnes deviennent bananes

and they split—en ze smeren ’em—et ils sont séparés

text into bits—tekst in bits—texte en morceaux

(these are actual results from Google Translate). Put them all together:

And some people go bananas and they split text into bits—En sommige mensen worden gek en splitsen tekst in stukjes—Et certaines personnes deviennent folles et divisent le texte en morceaux

However, what you get to edit is:

En sommige mensen gaan voor bananen en ze smeren ’em tekst in bits, which roughly reverse-translates as “And some people go for bananas and clear off out of there text in units of an eighth of a byte.”

Et certaines personnes deviennent bananes et ils sont séparés texte en morceaux, which is nonsense, because, as everyone knows, personne is feminine, so it should be ELLES sont séparéEs en moreaux, once they’ve become bananas, that is.

The text is in such disarray owing to poor segmentation (a segment should ordinarily be a complete sentence, or at least a complete clause up to a colon or semi-colon, but that is rare), and this split segmentation comes from poor preparation of the text by the agency or poor formatting by the writer. There are still people who use the spacebar instead of tabs and who fail to use full stops. They don’t read their own text before putting it into a machine to translate, and they then leave the translator to sort out, not only the translation but also the source text. All for three-and-a-half cents a word. Translation usually sells at around ten to 15 cents per word. (More for a bank, obviously.)

Poor segmentation was a feature of this job, so I asked if it could be sorted out. They didn’t do it. Remember: my job was post-editing. Their job was the machine translation part. But they machine-translated a text split into morceaux.

Where the text was actually coherently in full sentences, the AI translation was commendably acceptable. It wasn’t Shakespeare, but in any case the text was a telegraphic list of features of a cannon to be fitted on deck of a naval ship.

There was a price list for various aspects of this war material at the end, and the figures were mind-boggling. There was a time line for all aspects, including translation. Three months for a translation. I was given three days, with the great help of the machine, of course. I checked everything over. Vast swathes of it passed muster, even if the original text wasn’t in full sentences. I tidied a few bits of word order and made the terminology consistent where I understood it. I think I know a muzzle from a recoil.

The agency was indignant. I had changed 100% NOTHING, they said. No, I replied, I changed something, but it was on the whole a remarkably good AI production. Bravo AI, we are right to fear you and to look to our laurels, which will soon be yours! Summarily, the agency cancelled the job on the ground of quality deficiency and refused to pay for the three days I had devoted to the task. Not one cent.

I haven’t the energy to contest it. I will write and ask if they could send me the final version (as well as sending them this text), so that I can see what essential changes I missed. They will not refuse, I know. They will simply not answer. They’re in Italy and Italian law applies. Like I say, I haven’t the energy.

In short, I’m reduced to checking what a machine does, which is so good that it is taking my job from me, but if I don’t find enough fault with its perfection, I lose my job completely. Well, that’s what it seems like.

Reality check: what is checking?

Yes, what is “checking”? MTPE is the newish (since 2018) phrase meaning machine translation post-editing; it comes hot on the heels of revision and proofreading and checking, and all of these are different tasks, and they all depend on who gives you the task to do.

With proofreading, you read something just before it goes to press, or publication. Your job is to check spelling, grammar, context, flow, perhaps even style and the like. You read one document, and correct it.

Checking is whatever you want it to be. There is fact-checking, which carries great responsibility, and there is layout checking and there is “dirty checking”. When I worked at PricewaterhouseCoopers, they would come and ask for a dirty check. Not the full Monty, but just to take out the worst of the worst. That’s when the fun starts: Why did you change Member States to member states? I’d say, states are states, not States. States is not a proper noun, and only has a capital at the start of a sentence. The EU writes Member States, they’d say. The EU can do as it pleases. I proofread according to the rules of grammar, not the rules of the EU. You want me to learn the EU’s rules for my language? And who else’s rules? The Chicago Style Book? The Economist Style Book? The Washington Post? The Times? Encyclopaedia Britannica? Don’t tell me—DeepL? Do they even have a style book? You can probably ask DeepL to translate something in the style of DeepL and have it turn in eternity copying its own style into its own style.

Revision is checking what another translator did, and it is a useful exercise. The closer you are to a text, the less you see the wood for the trees. But, it involves a lot of work: effectively you mentally retranslate the text, with the help of the previous translator, but you’re constantly watching out for errors—theirs and yours: did they know something I don’t or is that just wrong?

What’s wrong with many revisers is they see it as their raison d’être to always cast everything into question, when they perhaps have less understanding of the subject than the translator does. Same with obstreperous clients trying to squeeze a discount.

The agency then returns the text to you to comment on the revisions. They pay a translator and a reviser, but the translator is then expected to revise what the reviser has revised. You may well ask, When does the agency do anything? I now say Do what your precious reviser says, and don’t bother me with their ignorance, but, otherwise, you spend an enormous time explaining why you’re right and the reviser is wrong. It took me nine hours to do that one day, and the reply was, Maybe the client was a bit hasty. Then there are those Member States, of course. Another time, a furniture maker didn’t know what casters are. Why don’t you say wheels? Because they’re called casters in the furniture trade. You are in the furniture trade, aren’t you?

Bottom line is that it doesn’t matter what you’re doing, because all translation agencies fly high with the goddess Nike. Checking, revision, proofreading, MTPE, they’re all the same: produce perfection; we don’t care how you do it; we don’t give a monkey’s what state the source text was in. Just do it.

No, I, for one, don’t do it, not no more. Because of arms contractors who resort to DeepL to cut time and expense and don’t even use full stops. And want me to sweep up their mess, and if I say, “Oh, what a good idea it was to use machine translation, because it’s perfect,” I don’t get paid.

Just the bits that have changed.

- Which bits are those?

A client wrote today, could I translate some revised statutes, which, thanks to AI, is what we now call articles of association. Could I base them on a previous translation I did for that? What previous translation? Our order no. XYZ whatever. I put my assignments in date order, I don’t use the many clients’ own systems of numbering. Mainly, actually, because some clients like to start a new thread for every last e-mail they send to me, so the date is useful to locate the first e-mail concerning the job on the grand time line of life. (Probably these are the guys who use the spacebar a lot.)

Sorry, but it’s a PDF, said I. You can OCR (optical character recognition) a PDF but you get line breaks at the end of every line, not every sentence. So it needs piecing back together (segmentation—remember?) So there’s no existing translation, other than what I sent them yon time. Do they want me to check the new version against my old translation and then not charge for the bits that are the same? Effectively, yes.

I wrote back: tell the ultimate client to identify which bits are different and put them (using complete sentences please, no word list) into a new document, and I’ll translate that and they can slot the new bits back into where they got them from. (I.e. cheap is okay as long as they realise cheap gets them half the work, the other half being for them.) I’ve known the client for 30 years and I still don’t understand these contretemps. Last year he told me to translate sehr gut (very good in German) as especially outstanding at his client’s behest (and swear to it on my soul, to boot) and I had to ask Wie bitte???

How much of what I do has to be for nothing? Can I only charge for the words that are new, but nothing for anything I translated before? Do I have to put the text into a format that’s even translatable? Do I have to wipe— … never mind.

What’s clear is that this professional I have known and honoured for many decades no longer feels able to assert his professionalism vis-à-vis his clients. He now feels bound to cow to their whim. The question of what liability is owed by a sworn translator to his client, vis-à-vis the state that appoints the translator, vis-à-vis God before whom the oath is sworn, is simply ridden roughshod over. Just do it. Primarily, I suspect, because that’s what machines do. They just do it. Without thinking.

Sworn translators

I’ve worked as a sworn translator for nearly 30 years. A new system came in whereby sworn translators are no longer registered with courts but with the central Ministry of Justice. We had to swear a new oath. To do exactly that for which we’d sworn the old oath. The Justice department, of all people, doesn’t know what an oath is, because it’s not sworn to them; it’s sworn to God. But try telling them that.

I swore my second oath in Dutch, before a judge of the Court of Appeal in Brussels, because my residence is in the Flemish Region. For all they knew, I could have been registered as a French-German translator with no knowledge at all of Dutch, married perhaps to a Portuguese-speaker who speaks it passably. Technically, you don’t need to speak any Belgian language to be a Belgian sworn translator. There were 200 translators in court that day, all swearing their oaths. None of them asked for a sworn interpreter for the purpose thereof. But the oath itself was contracted to I swear it. I kept expecting to hear the booming voice of God: Just exactly what dost thou swear?

However, there’s a problem. All that was to get onto the provisional register (after being on the register register for 25 years). Now, to get back onto the register register, I need a legal qualification that was introduced a few years ago to ensure that legal translators know something about the law. And to get that I must take time off work to go to college to get the diploma, which costs a couple of thousand euros. Or, I can get a bye on the diploma if I show my own legal knowledge and 15 years’ experience.

I have four diplomas, two Scots and two German. But, not Belgian. I have a testimonial from a Belgian lawyer for whom I worked in house for seven years. It’s glowing. But it’s not enough. I need to prove I worked for the state before the state took my second oath. They can’t themselves see the papers held by their own courts.

The maximum cut-off period for a tax audit is seven years. A while back, I threw out everything that was over ten years old, just to be sure to keep seven years’ worth in my possession. Now I have to find proof from 15 years ago. That’s iniquitous (and, with a ker-lunk, I say so here): having to prove I know something about law, when I hold an honours degree in law from Scotland, a combination civil/common law jurisdiction.

A colleague in Leuven is a Canadian barrister with degrees in the common law and from McGill, in Quebec. She has been a sworn translator for 13 years but she advises me she is not planning to requalify with the legal knowledge diploma. She will stop being a translator altogether and is planning to square her own circle by training, not as a barrister, but as a barista, maybe open a café. There is no future for her, she says, in translation, and I’m hanging on for dear life. She’s a good worker, and can’t get work. I’m a not an asshole and still can’t get work. The machines have taken over and the state is edging us out of the only domain where we can contribute and a machine can’t.

I could draw a parallel with notaries public, who are also a semi-self-employed arm of government, just like sworn translators. I take a swipe at notaries public here:

Just a few weeks ago, I engaged the services of a local notary pubic. He is very personable, chatty, no GPT, had free parking out front, a beautiful, spotless office and amenable, polite staff. But none of that is why I went to that notary public. I went to him because I had to go to a notary public to knock two letters off the name of my company: from BVBA to BV. The change is imposed by the Companies and Associations Code of 2019, and the deadline was the end of 2023.

My articles of association were slightly recast, his assistant misspelled my company’s address, but that was soon corrected (there’s always an error in a notarial document; there can never be an error in a translation). The charge was 1,580 euros, including VAT.

My first dilemma was: is it worth it? Five years before retiring, updating my articles? When the fees involved would take me six months to recoup and more? Would it not be better just to liquidate? Well, I went ahead.

The notary is the only guy I can go to for this service. No attorney-at-law can do it. I cannot bargain on the price. It’d have cost me the same 1,580 euros from the most affluent notary public in the country. Notaries public enjoy a certain monopoly position, being, as they are, a part of government. They register wills, house sales, corporate capital increases, and many other formal deeds, and collect the taxes on such transactions, and keep the records for future reference.

Their position is in large part an anomaly of history, but, for now, their function is protected by the government whose taxes they collect.

Sworn translators do not collect any taxes. And cost-free translations could maybe garner support for the central administration, making people believe my government works for its citizens (while casting its translators into penury). You don’t see that many street sweepers around these days. But there may soon even be more of them than there are translators for the state.

I wonder when the government will make all postal services free of charge, so people are reminded how respected and valued they are by their leaders (whose Justice department—them again—were overcharged rent to the tune of 400 million euros by the post office, which was more worried about concealing the excess charge than paying it back ...). Just to remind you: every last free translation is paid for by someone.

Electronic signatures

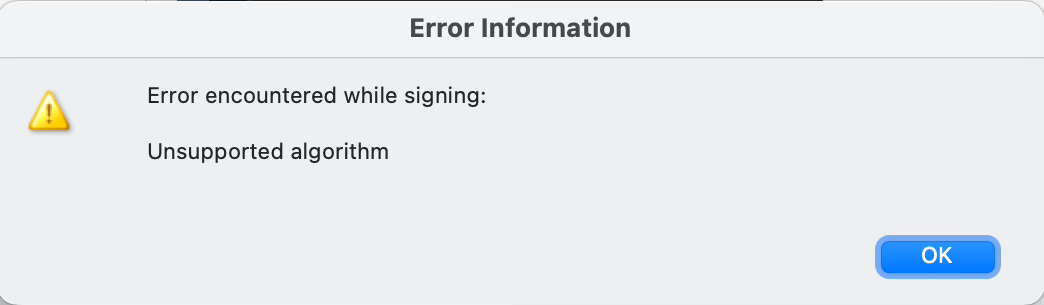

It was decided that, from December 2022, sworn translators would use electronic signatures based on Adobe Acrobat DC. I got the program, albeit under protest: it phones home and they conspicuously carried on trading in Russia when everyone else cleared off. I created the signature, went to put it on documents and got an error message:

It turns out that the Adobe solution—the one selected by the Belgian administration—has a conflict with new-style ID cards when used on a Mac. And that’s me. They admit to the problem, which is a serious impediment to my business, and have ignored two reminders sent to them recently after they’d announced the problem would be solved after the summer. Just how long after the summer they didn’t say. Longer than now, clearly. Eleven months after the system was introduced.

Vlaamse taalhulp

Recently a new client wrote that she was moving to Denmark and could I translate some official documents for her? Certainly, I said, and I quoted rock-bottom prices. She wrote back to say Thanks, but no thanks. The Flemish Region will translate them for her for nothing.

It’s called Vlaamse Taalhulp (Flemish Language Assistance). On the one hand, you can get access to translation services provided by an agency that the Flemish Region has entered into an exclusive contract with. (It’s not me, I can assure you.) And there is a scheme set up by the EU to make it easy for certain documents to be produced with translations already supplied from one EU language to another, like Dutch to English (Denmark understands the difficulty posed by its own language and accepts English for these purposes).

Meanwhile, under article 8 of the Irish constitution:

The Irish language, as the national language, is the first official language [of Ireland].

The English language is recognised as a second official language.

Under Maltese law, both Maltese and English have equal status on the islands. That actually makes Ireland and Malta the only territories in the European Union where English ranks as official. Make no mistake, what official means is not what you’re allowed to speak or what you must speak, it’s what the government speaks in its dealings with its citizens, and what its citizens must speak to it in return. That’s an official language.

Nowadays, around half of Belgium is Dutch-speaking, but, until 1969, the Dutch-speakers’ official language was not their own, Dutch, but French. The Belgian East Cantons are German-speaking, but they are in the Province of Liège, which is officially French-speaking, though they enjoy autonomous German-language rights. La police is die Polizei around those parts. However, the Belgian Court of Cassation has no criminal division that speaks German, and that is a contravention of the European Convention on Human Rights, to which Belgium is a signatory.

However, it is not for the purposes of the Irish or the Maltese that Denmark accepts English documentation, but because English, under the influence of the British and the Americans, has become a world language. It is by the merest of coincidences, since Britain’s withdrawal from the EU, that English is still an official EU language. But the Belgian government, under pressure from Brussels (pardon the oxymoron) offers services to its citizens that cut its own official translators out of the picture, from a sector that is already suffering badly as a result of digitisation, and in particular for a language that isn’t that official anyway.

The government asks me to pay 2,000 euros for a course to remain a sworn translator

five years before I’m due to retire, or

to produce evidence from 15 years ago,

which is more than twice the period for which records need to be kept for tax purposes. If I obtain the qualification, I can remain a sworn translator, but

the Flemish Region is undercutting me on the very services I will have qualified to do. And,

at the same time, there is no guarantee of any work at all from the state.

There’s hardly an analogy for this but it would be like selling a franchise to a train operator to run official rail services for the government, and then telling it that the government, and only the government, decides when any official train is needed, and then it simply doesn’t ever ask for one. Meanwhile, some private individuals who would need a train are transported up and down a road parallel to the railway line in buses provided by the government: free of charge.

It’s interesting that the Minister of Justice has just resigned for incompetence in his ministry. That, I believe.

The Golden Shot

A blue-chip law firm wrote to me. They were in litigation on behalf of a client and wanted some documents translated. Thirty-five of them. Not all of all of them, however. In some of them, they merely wanted a few articles translated and not even all the definitions, just two or three. Could I quote please for free and sworn translations?

They all were in PDF format, so they needed to be opened, OCR-converted, copied and pasted into Word, and then the relevant bits needed sorting out. Thirty-five times.

I have in the past written to ask, “Why not just send me what you want translated so that I can give you an estimate?” But this has failed to impress and I got a sense that it would fail to impress in the current case, so I took an entire day and did this laborious task, because I had noted that a lot of the documents were signed by somebody with whom I used to share an office, who was then a trainee and is now a powerful partner of this kick-butt law firm.

Two full working days after the more than reasonable estimates had been submitted, I was informed that my offers were rejected—free and sworn.

One thing that rejections all have in common is: they never tell you why. So, in this case, I asked. “Can you tell me why I have been rejected?”

“The client found a better offer from a translation office.” Now, it would not be the first time if this translation office were now to call and ask me to do some of the translation, but they haven’t thus far. It has happened in the past. My quote is rejected, but the firm that wins the contract at basement prices then offers me a few crumbs from their table, as they get machines and lackeys to do the work I would have done as an expert. But, alas, not here.

Nothing to lose. Really, nothing to lose. I let them have it, in a forceful but controlled manner. Not a cluster bomb. A keyhole strike.

You could have negotiated with me freely, openly and honestly. Don’t you do that? Negotiate for the benefit of your clients?

I don’t want to be childish, but what translation agencies do is not translation: they have translations done by translators, like me.

They run the text through machine programs and then translators are paid three to three-and-a-half cents per word to make up for the sometimes unintelligible results. The agencies squeeze clients and translators in both directions. Like lemons.

The real experts cannot survive in this. We’re going to hang up our hats and leave everything to the translation agencies and the machines.

My earnings have fallen below 500 euros per month. Some months I have no income. Usually July and August, while everyone is on holiday and I pay my rates. I pay my accountant more than I pay myself. I don’t expect any special treatment from you. [A partner of yours] and I shared an office some time ago, and she herself can attest to my professionalism. By the tone of this you can manifestly gauge how bad the situation has become. Nothing to lose.

Myself and a Canadian barrister, who also provides quality work [nearby to here] will probably leave the market. Two fully qualified lawyers are leaving the translation market here, because we can no longer survive with the knock-down prices charged by the discounters. We just can’t survive. And then … you will have to rely on the translation agencies and the machines, because there will be no more experts.

However, I look forward to spending a day making a quote for you on another occasion. Well, I do have the time.

The agencies bid low, knowing they have the networks to be able to farm out just about anything. They undercut any price that a self-employed person can quote, way below, to be able to secure the job. Once they have the job, they farm it out at pitiful rates of three cents a word, after churning it through a machine, without so much as a second glance at the result. So, instead of the client paying 14 cents a word from a self-employed sole trader, they get the work for 12 cents a word after it’s been perfected by the sole trader, who’s now getting three cents a word, leaving a fat nine cents a word for the agency, for doing a bit of admin. Discussions about quality? No problem, we will cut the translator’s fee for being so sloppy with our precious client work. In fact, we’ll just pay them nothing. Oh, the client? Nonsense, there’s nothing wrong with the translation: pay up or we’ll sue.

Use us or lose us. Meanwhile, we think of a number, halve it and cross our fingers.

The Golden Shot of the title to this section was a live quiz show that was broadcast by Britain’s ATV on Sunday afternoons back in the 1960s and 70s.

It was hosted by comic actor Bob Monkhouse and its format was that an operator called Bernie directed the aim of a crossbow bolt (on a suitably secure rig) towards a target, the bullseye of which was an apple (à la William Tell). The trick was that he was blindfolded.

Contestants gave instructions to Bernie the Bolt to direct his aim left, right, up a bit, down a bit, whatever. They had 30 seconds. They had one shot, and if they hit the apple, they won the prize. If not, too bad.

They had one bolt, one shot, 30 seconds. No negotiation.

Sale of the Century

or “Please take one”?

You may be interested to know—the Canadian barrister I mentioned and I aren’t, so the field is clear as far as we’re concerned—that a Brussels translation firm of my acquaintance is selling up. Odile and Ahmed are moving on to pastures new. My Canadian friend put it less rosily and more rattily, but there you are. It’s not that unusual for any firm in any sector to be up for sale. But this is no take-over; it is an “all offers considered.”

With prams and children’s toys, they get put at the end of the driveway for anyone to take who wants them. I don’t think this firm is quite there yet, but, I do wonder.

Sale of the Century was an Anglia TV quiz show hosted by Nicholas Parsons.

Who Wants To Be A Translator?

Who Wants to Be A Millionaire? is a quiz show franchise owned by Sony.

In 1992, I chose for a career in legal translation because I believed I had something to contribute and I wanted to be able to work at my own pace and be my own boss—independent; because I’d seen enough of law-firm politics to not want to have anything to do with them, not on the inside. One cross-border firm I worked for as a translator for seven years imploded like the Titan a few years after I quit.

My principles have cost me dearly and I have made enemies by being stubborn about what is and is not right and proper. I staunchly refused to be corrupted by one Coudert Brothers associate, who offered diplomatic discount cards nicked from the Italian embassy. I refused to comment when one partner said he looked down on accountants because comptable in French includes the word con. I made enemies: some rightly, some foolishly. But, so dearly have I paid for my principles, I will not buck to any trend now. If all that lay ahead for me were paralegal work, then paralegal work I would do. To return to the law, five years before retiring, I’d need to requalify as a solicitor. Another diploma.

Translation has no future for humans. It’s great the way people can communicate these days using online resources; which scrape everything they say to each other, with no privacy, with no discretion. Go on, I challenge you: do it—send a WhatsApp message about double glazing tomorrow, and see what happens. All fed into the big AI monoliths; and there’s nothing learned by the humans who do the feeding: no conjugations or declensions; conversation skills; prepositions with dative; comma rules; no thinking; no nothing.

Two weeks ago, I translated a birth and a marriage certificate from Ukrainian into French. I don’t speak Ukrainian that well. It took three days to transcribe the photographs of these beautiful, exquisitely engraved certificates into Word documents, and then to laboriously translate them. I’m a linguist: I loved it, I absolutely relished it.

Like the Italian Job referred to at the beginning, it took three days. But it brought great satisfaction and some lovely exchanges with the client. And, unlike the Italian Job, it actually paid. Less than 100 euros, but it was worth it. Because the Ukrainian client was human. And the Italian agency wasn’t.

A monumental translator

Translation will not die. It will continue, but not as it was before, and not as it used to be.

My grandmother hailed from Galloway, the lost, southwestern corner of Scotland, where moorland and farmland are about all that offer themselves as an economic basis. To the east of Newton Stewart, a principal market town of the area, out along the Old Edinburgh Road, you can find, high on a hill, an obelisk-styled monument to one Alexander Murray.

I have visited it and I have paid homage to it, and to the shepherd’s croft, which lies in ruins opposite the monument. I can do no better than to quote from H. V. Morton’s sequel to his travelogue In Search of Scotland, his 1933 work In Scotland Again (pages 110 et seq.):

There was no one on the road that runs from New Galloway to Newton Stewart, so that I had to climb the hill to find out why men had placed an obelisk on the top of it. The climb was easy, a bit wet and peaty in parts, but it was worth it, because Murray’s Monument commemorates one of the greatest stories not only of Galloway but of Scotland...

Less than a century and a half ago, a man climbing these hills might have heard a young shepherd boy talking to himself, and the God-fearing climber might well have fled the hill in the belief that the boy was bewitched, for he spoke neither in Scots nor English. With a book on his knee, he would recite the Lord’s prayer in Hebrew. If the eavesdropper remained long enough, he might have heard Greek, Latin, Arabic or Anglo-Saxon. This lad was Alexander Murray, a shepherd and son of a shepherd, who with no encouragement and the most meagre aids to knowledge but urged onward by the genius within him, became one of the greatest masters of oriental language and dialect.

Genius has no rules. If it is great enough, it will fight its way out of a man as it fought its way out of young Alexander Murray while he watched his sheep on the hill.

He was born in an old ‘biggin’ at Dunkitterick in the parish of Minnigaff in the autumn of 1775. He was a delicate child and precocious from the beginning. At the age of six, he begged to be taught to read. In the winter evenings his father would painfully trace out the letters of the alphabet on a wool card, a charred heather stem serving as his pen. Young Alexander sucked up knowledge as the parched earth absorbs rain. His eager mind, it would seem, knew from the start exactly what it wanted; but how to find it in a clay ‘biggin’ or on a wild hillside in Galloway? If the will is strong enough there is always the way.

There is something almost terrifying in Murray’s determination to learn, something akin to the processes of nature where events move instinctively towards their fulfilment. And his first triumph was a chance copy of Salmon’s System of Geography. In this book was printed the Lord’s Prayer in the various languages of the world. So the seed was set.

When Murray was ten years of age he could read Caesar, Ovid, and Homer. He had taught himself the Hebrew alphabet from the headings prefaced in the 119th Psalm! The pride of his life was a Greek Testament. When the lad was about twelve, his father moved nearer to Minnigaff and Alexander was sent to school there. The parish schoolmaster was astonished by the boy. In a few weeks a good working knowledge of French and German was added to his accomplishments. Then came a copy of the Psalms in Hebrew. In a few months Alexander Murray could read Hebrew, although he had never heard one word of this language pronounced! A copy of the Arabic alphabet came his way. He began to learn Abyssinian from a few stray passages in the Ancient Universal History! Before he was sixteen he was studying Anglo-Saxon and Welsh.

Then he encountered one of those characters whose function in life is to help on genius and receive no laurels. This was a smuggler named M’Harg, a good-natured, generous fellow who was tremendously impressed by the learning of young Murray. He went to Edinburgh with a sack of smuggled tea and so enthusiastically did he sing the praises of the young Galloway prodigy that curiosity was roused and, at length, young Murray was asked to visit the capital.

One morning in November 1793, the genius and the smuggler set off together. M’Harg carried on his shoulders a sack whose contents one can only imagine and young Murray bore—beloved burden of the ambitious Scot—a sack of oatmeal. Murray was a capable-looking youth with black hair, deep-set hazel eyes, a determined jaw and, that pointer to fame, a large, straight nose. So they passed along the road together, and those who saw them would have seen, not one of the greatest sons of Galloway and his strange friend but a middle-aged pedlar and a country lad in a coat of hodden grey.

Murray was examined by three professors of Edinburgh University. Whatever he lacked in finesse he made up in the scope of his studies. The professors were astonished by him. Murray found himself the holder of a town council bursary.

In the short life that remained to him the shepherd boy from Galloway won a European reputation. He became one of the greatest linguists of his time. He mastered Chinese, Sanskrit, Hindustani, Persian and Icelandic. He specialised in the Abyssinian dialects. When the governor of Tygri in Abyssinia wrote a letter to George III, the only man in Britain who could read it was Alexander Murray.

At this time Murray, who, like many a humble Scottish lad, had heard the call of the ministry, was in charge of the parish of Urr in Galloway. There he found a wife. There he studied. There he preached dreary and long-winded sermons. Then Dr. Moodie, Professor of Oriental Languages in Edinburgh University, died. This was the professor who had examined Murray when he tramped from Galloway to Edinburgh with his sack of meal. The young scholar was elected in his place. One wonders what Murray might have done had he been blessed with health and spared to enjoy the old age in which so many university professors seem so happily embedded, but, alas, he broke down in health and died of tuberculosis in his thirty-seventh year. He left behind him more than knowledge. He takes his place high up in Scotland’s splendid roll of fame, an example to all those who, with nothing to help them but their own courage and determination, find their footsteps faltering on the road to achievement.

I climbed down from the Murray Monument to the road that goes to Newton Stewart, thinking that a father with a lazy and indolent son might do a lot worse than climb this hill with his boy and tell the story of the young shepherd. I suppose, however, that a modern boy would shatter the sententiousness of his parent with:

“Very interesting, dad, but, of course, the fellow was a genius.”

I am afraid there is no retort to this.

Alexander Murray of Minnigaff, esteemed son of Bonnie Gallowa’, is why I became a translator.

Across the world, with all these communication possibilities, we see naught but human antagonism. To what purpose do we put all these means of communication in other people’s languages? To shoot them dead?

.

A "like" for yet another wonderful piece of writing, but not liking your trials and tribulations. I'm not a translator, though I've done my share of translation, so I am able to empathize with much of what you've written. In my line of work, I need to use several languages for daily tasks, and I do indeed use machine translation. It saves me time in that it produces a product that I'm then able to edit and plug in my experience and knowledge to make it right. But, no machine translation is go to go. It always needs work, and that work must be done with someone with actual knowledge, experience, and I dare say, talent to make it right. It's not easy work, nor is it quick, if you want the end product to be of the highest quality. I feel for you.

Tangent: I recently ran into an interpreter working freelance. Not entirely sure about who she works for and what the conditions are, but she also works as an interpreter for the Brussels police. I.e. when a foreigner speaks to the police, but either speaks no French/Flemish (or simply wants to be sure that he/she doesn't make potentially disastrous mistakes in responding), they are afforded the services of an interpreter certified (licensed?) by the Brussels govt. The Brussels govt. pays for the service. She said it's a good side-gig, and pays many of her bills. I'm sure that, in the future, this might also be taken over by Google translate in conversation mode (I've used that recently to good effect in Turkey), but for the next five years, it could serve as a stop-gap?