In my recent article

Is AI tangible proof of God?

CAT is a type of computer software that builds a memory of what translators translate: in short, it means computer-aided translation, and it is a godsend to the modern translator.Thanks for thinking with The Endless Chain! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work. Assuming the world doesn’t end first.

I have embarked on what is regarded by some as a frivolous examination of whether AI and its intangibility could ultimately deliver tangible evidence a contrario of the existence of God, whose existence, by some, is denied owing to a want of such tangible evidence. Even die-hard believers cast looks of doubt at my arguments.

By being taken as based on fact, the comparison of God to a great military power, often as a result of stories entailing the wrath of God (the Great Flood of Noah, the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, the deaths of the Egyptians as Moses crossed the Red Sea) gets construed as a basis for the denial of God: if God did all that, why can’t He stop a war? Such events are more apt, however, not for concluding that He doesn’t exist, but that that God exists but is not a God of power as we comprehend power to be.

If He did all these things, the non-believer asks, how come He destroys the innocents as well as the guilty? How do you know it’s Him? How do you know they’re innocent? Innocent of what? Or is God a wrathful deity who wreaks His vengeance without even telling you what you’re charged with? Perhaps shit just happens. I have evidence I can explain, and evidence I can’t. Just as non-believers do.

Predicating God on the idea of a great military power is, I contend, a false precept: the world has seen many great military powers, from Alexander the Great and the ancient Romans, to Atilla the Hun, the Egyptian pharaohs and the European empires, and none of them has prevailed over time. And none that prevail now will, either. If you contend the contrary, name me one from the past which we might take as an example.

Instead, God is predicated, not on power as a force of duress but on love – the power of love, if you like – as a force of compassion; and military powers are not known for harbouring that kind of philosophy. We seek proof of the existence of God in a catalogue that doesn’t even list Him.

In an article by Hannah Devlin, which appeared in The Guardian of 7 July 2023 (AI likely to spell end of traditional school classroom, leading expert says), a British computer scientist based at the University of California, Berkeley, Prof. Stuart Russell, says of AI as follows:

“The large language models in particular, we have really no idea how they work. We don’t know whether they are capable of reasoning or planning. They may have internal goals that they are pursuing – we don’t know what they are. Hundreds of millions of people, fairly soon billions, will be in conversation with these things all the time. We don’t know what direction they could change global opinion and political tendencies. We could walk into a massive environmental crisis or nuclear war and not even realise why it’s happened. Those are just consequences of the fact that, whatever direction it moves public opinion, it does so in a correlated way across the entire world.”

He’s talking about large language artificial intelligence. If I were to posit that he is talking about the Mujahadin, the US government, Elon Musk, the Chinese Communist Party, or the European Union, there comes a point at which what he says makes no sense. It would need further expansion to get his drift.

For instance, which of these organisations has no reasoning or planning capability (aside, it sometimes seems, from Mr Musk)? How much conversation is there going on between people and these organisations? Which of them would have the potential for a massive environmental crisis or nuclear war? And which of them can move public opinion across the world, in a correlated fashion?

What marks the difference in seeking a parallel for God in our manmade world between comparison with geopolitical organisations and a comparison with AI is that we know, or can find out, or, at least, someone knows, how such organisations operate. Yet, for all we know what AI can do, and we know how it was created, what we don’t fully understand is how it actually produces what it produces and, like with all things unknown, there is an element of human fear in that.

So, what is it that he is talking about? What is large language artificial intelligence? In that, I mean as a functioning concept rather than in the details of its circuitry. Well, the closest comparison I can come up with is God.

This is not a posit that AI is God (although if He created us in His likeness, might He not also have created AI in his likeness?) Aside from that tangential remark, the crux is that, if denial of God is predicated on the impossibility of such a being acting and intervening, or not intervening, in the way it does, or does not, and on the scope that it does and can do so, and, given the hazards that that could entail, why would anyone believe that AI exists in that format and yet continue to deny that God might exist on the same, or a vastly similar, model? There has been nothing like AI on this Earth since time began. Now we have it: a thing that can be viewed as something more than just a machine of Man’s creation. The comparison with God holds up against the criteria Russell cites.

We have no idea how He works.

We don’t know if He even reasons or plans. We think so, some of us. And others reason that He must reason. But whether He actually does so is unknown for certain. Still others attribute everything to coincidence and bad or good luck. (And then anthropomorphise that as Lady Luck and Dame Fortune. Perhaps believers in God effectively do the same thing.)

We don’t know what opinions and tendencies could arise from AI. We don’t know what opinions and tendencies could arise from God, either, and with that lack of knowledge in our own minds, we have repeatedly tried to fill in the lacunae in our actual knowledge of Him using our presumed knowledge of Him. We know that He knew one disastrous consequence of His plan: God knew His son would be executed. And we also know that He knew that that was for the best.

When one walks into a crisis or a war, is that the fault of the unseen system that creates conditions, or of him who walks?

Is correlated action across the world a potential danger or a potential benefit? A universal belief in the one God would be a benefit, just as globalised economies are a great benefit. But globalised economies bring with them the danger of globalised exploitation, and that is not a great benefit. Everything in Man’s world has a flip side, depending on how it is that Man goes about using it. The great benefit of universal belief in God would quickly, according to the Bible, result in the end of the world. And, somewhere, the believer has to reach outside the box to find in that prospect a benefit. Well there is one, according to the Book of Revelation, which is this: He will wipe every tear from their eyes. There will be no more death (Revelation, 21:4).

The non-believer says that this will not happen, in any event. And therefore they have nothing to fear or to aspire to. The believer, however, has to conjure the idea that the end of the world is the ultimate great aim for the world. That its destruction has been the sole aim of God from the inception. And, to the believer, that can only betoken one thing: that what comes after the end of world will be more wonderful than anything we can even conceive of. For, God, to be God, and to exist, has to have a purpose.

Suppose we organised a train journey, by purchasing a train. We want to take a large party of schoolchildren to a desolate location, where they will disembark and then dismantle the train in order to build an adventure park. There is an architect who knows how to do it and has foreseen the tools the kids will need. We are ready for departure and a whistle sounds. Off we go.

Do the kids need supervision on the journey? What if they play with the lightbulbs and chuck them off the train? Or get into arguments and start fighting each other? We don’t want that. We don’t want the train ruined before we get to rebuild it into our adventure park. So, we have set up a code of rules, with things like asking the children to show respect to each other, to not stain the upholstery of the carriages, to not unscrew lightbulbs and throw them out of the window. To flush the toilets and present their tickets in an orderly fashion to the ticket inspector.

Some of the children may break the rules. May climb onto the roof as we travel along, and may even fall from the train. But, if all is well, the train will arrive in a more or less complete state at the destination, and be ready for the work that lies ahead.

But perhaps they are not schoolchildren. Perhaps they are Jews being transported to a concentration camp. In that case, we don’t much care what state the train is in when it arrives. There will be no adventure camp, but only death and then nothing. If they climb on the roof, they will be shot. If they fight, they will do our work for us.

The train with the schoolchildren is a model of love. The children must love one another and they must love their environment because, even if the train will no longer be a train when it arrives at the destination, we need it to be whole and entire for the next stage of our project. The rules are there to ensure an orderly journey to the paradise that awaits us.

But the train with the concentration camp inmates is a model of power: the occupants are enforced, not under rules but under a regimen, which offers only death to those who will not acquiesce in death. Their fate is to die regardless, and, because of that, how they treat their conveyance is really of no matter. They may exploit it for their purposes because, in the end, not only the train but its occupants will be destroyed anyway.

Which of the analogies attracts most? Which repels? Which of them, even if you don’t believe, reflects best what you consider would best approximate to our notions of God? And which would approximate best to our notions of AI?

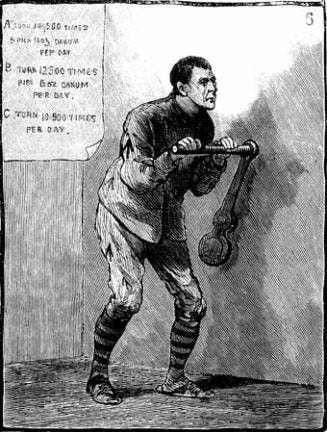

We see in our own lives the purpose of purpose. Purpose lends drive and brings achievement, when it is achieved. It is not vacuous. In Victorian prisons, they used a device that prisoners were obliged to operate, turning a handle, endlessly. It generated no electricity, nor did it mill any corn. It simply turned, and the difficulty of turning it was regulated by tightening or loosening a screw. It was warders who turned the screws, and it was the screws that gave the warders their nickname. The device was intended solely as vacuous punishment and, as its purpose, it served that purpose well. But it served no other purpose.

If for a second I considered God not to have a purpose, I would cease to believe on the spot. I would destroy the train and all in it, if I could. If it were carrying schoolchildren, I would do so out of spite, for why should some cherish a hope I know to be hopeless? And, if it were carrying concentration camp victims, I would do so out of mercy. For if death is their fate, I would thereby save them the discomfort of their journey towards it.

God’s purpose is the destruction of the world. And in that, there must be purpose. And I will know what it is one day. Or this entire life of questions will have been no less futile than the screw device in a Victorian prison.

There are no billions in conversation with me. So, I will not sway their opinions and tendencies. Nor will anyone, with whom billions are in conversation. Only those who talk to billions will sway opinions and tendencies; but the billions whom they sway will not be in conversation with those who do the swaying. Conversation is one on one. No individual can converse with billions. Only organisations can talk to billions. And only AI can have conversations with billions. AI, and God.

Billions will soon be in conversation with AI, as billions are already in conversation with God. If AI beckons the world’s or our race’s destruction, then perhaps it is AI’s will that that should happen. If it does so predicated on Man’s psyche, then it will seek purpose in what it does. Otherwise, it is not of Man’s psyche.

Its purpose may be nefarious, could be to secure its own rule and might. But he who rules mightily must have someone to rule. And when there is none other to rule, then one can but rule oneself. Rule of the self is the ultimate ordinance from God: that we should exercise jurisdiction first and foremost over our very selves.

If AI is God, I seek the philosophical fallacy in this conclusion, for then AI’s purpose will be God’s purpose.

If AI is like God, then it will seek purpose, because God has purpose.

If AI is unrelated to God, and is purely a product of Man, then it will likewise seek purpose, for Man seeks purpose in all he does, selfish though it can of occasion be.

If AI destroys the world, then whether AI is God or AI is like God, it will be God’s will that it does so. And perhaps, even, it will be God’s will that does so.

But if AI destroys the world to no end, for naught, out of wantonness and whimsy, then that will be proof that AI has nothing to do with God. It could be proof that AI has something to do with Man. But it would most of all prove that the Devil had won. For whoever would be left to take note of the fact.