Milan Kundera: a life reconstructed contra preferentem

Eulogising on a subject yet to be learned

“The 20th century is the century in which all the small countries have disappeared.” Milan Kundera, in a Belgian TV interview given in Paris in 1980.

Kundera’s last, 2013, novel, The Festival of Insignificance, was reviewed in 2015 by The Guardian’s Alex Prešton (as he once spelled it), in these words: the reading process becomes a pitched battle between hope and boredom, with the latter crushingly victorious … a novel that promises little and delivers less … Kundera’s recent(ish) output feels like a series of retreats into mere cleverness.

Aside from The Unbearable Lightness of Being, I’d never heard of any works by Milan Kundera until he passed away a few days ago. To be quite honest, though I’d heard of that work, I couldn’t have told you it was by him; nor, had you told me his name, could I have told you he wrote that work. In that, The Unbearable Lightness of Being and Milan Kundera are in honoured company, and the only regret to be voiced, if regret there should be, is that the poor fellow should need to die before I took any note of who he was and what his life’s output was.

In 2021, actress Olympia Dukakis died, and I wrote this conversation with myself further to that:

- Olympia Dukakis died on 1st of May.

- Did it?

- She.

- Did she?

- I saw her in Steel Magnolias, thought she was great. They were all great in that film. Sally Field, especially. She was a great friend of the theatre, apparently.

- Who? Sally Field?

- No, well, yes, probably, I don’t know, I didn’t read her obituary yet.

- Who, Sally Field’s - is she dead?

- I don’t know if she’s dead, I’d need to check. No, I meant Olympia Dukakis’s.

- You knew her?

- No! I didn’t know her, never even met her! Don’t be silly.

- It’s just, you seem to know quite a bit about her.

- Yes. Well, I do now. I read the obituary. Daft, isn’t it? That we only find out how much we love and admire someone when we read their obituary.

- You mean, people’s obituaries should be published before they die?

- Well, the Duke of Wellington’s was. Or something. Yeah, maybe. Then we know who we’ve lost before we lose them.

- You’re daft.

- I like to think so.

- Sally Field’s alive and kicking, anyway. Go read up about her before her obituary’s published.

A eulogy is a speech given at a funeral to celebrate the deceased’s life. If it’s a good speech, it’ll be memorable; if the deceased was good, they’ll be memorable. But, is a good eulogy intended to tell the dearly beloved gathered at the funeral what they already know, to advise them why they’re even there, or to entertain them? All three, I suppose.

We’ve attended remembrance day ceremonies every 11 November, or thereby, since 1919; yet, every 11 November, we return to cenotaphs and war memorials to do it again. Is that because we’ve forgotten to remember in the meantime? Or because we want to remember again, one more time, with feeling? Is it to wallow in remembrance that has never quit our hearts? Or is to strengthen future resolve?

I recall the first time I visited the concentration camp memorial site at Dachau, just outside Munich. I bought and sent a postcard to my parents, on which I wrote three words: Today, visited Dachau. I didn’t know what else to write. Having a lovely time, wish you were here? The postcard depicted the simple message at the memorial’s entrance, inscribed in Hebrew, French, Russian, German and English: Never again. With wartime remembrance, I would like to feel a sentiment that the memorial itself is likewise a promise, an undertaking, a resolve to not only honour those who’ve died in conflict but to redouble every effort to prevent future deaths in conflict. I’m not sure that that is always so. I think it is less so when the monument speaks of heroes who died in glory. Even Jesus didn’t die in glory: He died nailed to a piece of wood. When soldiers die on battlefields, do they utter Jesus’ last words? Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.

Death is the part of life that pencils in the last shade of perspective. There were those who reviewed The Festival of Insignificance, Tessa Hadley, for instance, who, unlike Preston, praised it, as day-lit and funny and crisply elegant. She cites one of Kundera’s multifarious short statements about life, living and the world: “No one has the right to pretend to be reconstructing a human life that no longer exists.” With the writer’s passing, it sounds like an admonition from the grave.

It is what snippets of writing, of saying, of discourse, say to the reader or listener in the moment of reading or listening that alert one to the significance of the writer. Some books I’ve read were erudite and worthy, informing me, as if I was at their writer’s funeral; some I read because I knew the writer and wanted to know more – they were reminding me why I was even there; and some I read simply for the entertainment. But, of them all, I can quote very few passages and, were I to do so, I’d be back rooting through their pages to ensure I got the quotation quite right and rereading them to be sure I’d understood them correctly. I returned recently to Shakespeare’s Hamlet to read the speech that begins To be or not to be. I recited it to myself late one night, whilst sorting laundry. I don’t think we’ll ever hear the lines as they could be heard in the head of William Shakespeare when he wrote them in 1600. How would you say That is the question without knowing it’s the next line?

What, in these few days, has struck me about the writings and sayings of Milan Kundera is their consistent ability to halt me in my tracks. And what has stopped me more in my tracks than anything else that he said is his observation that the stupidity of people comes from having an answer to everything; the wisdom of the novel comes from having a question for everything. I believe that the first question raised by anything that anyone says, should be Is that right? Not, is it right in its absolute terms, but is it right in my absolute terms.

Ironically, objectivity is only achieved through the onlooker’s own eyes. And it is only achieved when those eyes cease to be the onlooker’s. But the onlooker cannot possibly achieve the objectivity of all, for, in endeavouring to achieve that, they will inevitably devolve into the global chaos we live day in, day out, in which no one’s subjective objectivity ever reigns supreme. Objectivity is only achievable in any given respect where the assessment is anchored in a principle that is unwavering and unshakable. It is relatively rare to encounter such principles, and those that do exist, get pitted with bitter experience; like Kundera’s aesthetic, they evolve linearly, which is, I think, an elegant and clever way to say change.

How they change is to become encumbered with qualifications, nuances and outright selfish excuses. To be a writer does not mean to preach a truth; rather, Kundera said, it means to discover one. If I read his entire oeuvre, would I discover what it is, that truth? Or would I discover another, which he inserted nonchalantly but which speaks to me in volumes? What is the truth that Milan Kundera discovered? Did he ever tell the world, as it tries to reconstruct a human life that no longer exists?

Kundera spoke of the unbearable lightness of being. And being was, for Hamlet, an existence he questioned as unbearable. If we took Kundera at his word, we’d not dwell upon what he wrote and said, we’d not try to understand him or to understand his world. We’d not even assess whether he was right to say that the 20th was the century in which the small country disappeared. It was, after all, the century in which his own small country became smaller. But we can look upon his writings as a spur, and as an inspiration, to assess, understand and, indeed, dwell upon ourselves and our own worlds.

For a writer’s message is not simply a narration, but is crystallised as relationship when those to whom it is narrated take sustenance from it. It’s when a writer’s writing speaks to the reader personally, and intimately, that the writer achieves objectivity. Whereas subjectivity is the hallmark of all interpersonal relations, hence defining them as that, that subjectivity is ruled out when what strikes the reader as right about what has issued from the author’s pen achieves its rightness through its erga omnes relevance. And it is that which endows it with objectivity: when right is rightly right irrespective of who they are, to whom it is spoken. This is a cathartic process of epiphany, which can be very profound in forging a relationship to a writer whom one has never known – in fact most writers. Ukrainian pacifist and philosopher Vlad Beliavsky describes it as his relationship to the Roman philosopher Seneca; and I, indeed, have a like relationship to Vlad Beliavsky. Frigyes Karinthy’s six degrees of separation would, if consisting of such relationships, portend a very fruitful world in which to coexist.

Returning to Alex Preston, what is mere cleverness? What, is that, Alex? Mere cleverness? Is it pedanticism? Sophistry? The argument of a tricky lawyer? The cleverness of a dismissive critic?

It’s an odd reflection in these days, with Kundera’s death still so recent, but it is fitting that Preston expressed his reservations about The Festival of Insignificance when and how he did, for his job is to criticise and it would be below him to do anything less than to honestly, and eloquently, explain why he feels about a work the way he does. This, however, I feel is a little below him, since I don’t know what he means with it – mere cleverness. There are retrospectives in many mainstream quality publications right now on the matter of Milan Kundera’s contribution, his literary legacy, and I’ve read a few of them. The themes that mark this author’s time are there in abundance: his flight from Czechoslovakia, his Frenchification, his 1984 blockbuster novel, his readmission to Czech nationality, for which he notably said, Thank you (which could be taken as Gee, thanks or even So you should, supposing he even asked for it …).

But cleverness, whilst present subliminally in all these accounts, isn’t expressly mentioned. What Milan Kundera’s cleverness does for me is to make me make that halt and do that thinking on whether that which he, not Preston, says is, after all, right. In that, Kundera was undoubtedly clever. It is not especially clever for me to halt others in their tracks and provoke them to question my rightness. But it is clever to halt them and provoke them to question their own.

However, that is not the cleverness to which Preston was alluding, if only because Preston alluded to it dismissively. If Preston was sincere in his assessment, then it flies in the face of Kundera’s own avowal not to preach a truth. One of them could be right: Preston, or Kundera. Or both of them could be wrong. Kundera could be preaching truth when he says a writer must not preach truth. And that may be cleverness for cleverness’s sake, or a truth that Preston hadn’t yet discovered. I don’t think that, if Alex Preston were writing that review today, he’d make such a statement; and it’s interesting to consider why he wouldn’t: perhaps because it’s not fitting to say such things at funerals.

There’s another strange element that crops up in descriptions of Kundera’s life: the accusation that he betrayed somebody back in communist Czechoslovakia, an accusation he later vehemently denied. The accusation itself is forceful enough to cause one to halt in their tracks. To ask can that be right? Kundera’s supporters will undoubtedly place great faith in the man’s denials; his detractors, if he had any, would place faith in the newspaper report and, despite their reputation, newspapers do occasionally report the truth.

I feel a little like an observer of the Mona Lisa who discovers a daub in an obscure corner, where Jackson Pollock has experimented with a toothbrush: I may be told the daub isn’t there and focus on the inscrutable smile instead; but once it’s drawn to my attention, I may question whether it’s there or not, but I can never erase the memory of it, even regardless of whether I’ve seen it. It’s like inadmissible evidence in a jury trial. The jury may be instructed to scrub it from their memories, but that act will only impregnate it into their memories. What happens at trial should not be dependent on whether or not the evidence was legally admissible but whether its omission was fair, its inclusion unfair, and what motivated the parties’ and the court’s stance vis-à-vis the evidence. In the case of Kundera’s alleged betrayal, if it were true, what impresses me is what some would dismiss as my gullible readiness to see good in people: the view that that could betoken a youth of confusion, in which his linear evolution had not yet taken the path it later would; it would betoken a later firmness of resolve, demonstrative of a rejection of his earlier acts; it would betoken a rejection of an aspect of his life that would, if pursued, have resulted in a different Milan Kundera to that which the world came to know. And, unfortunately, it would betoken a reconstruction of a human life that is no more.

We may conjure the following: is he a worthier man who commits a crime and subsequently abhors his own calumny, or he who commits no crime? The law would have it that the latter is the worthier; if asked, many might say the former is the worthier, albeit with due qualification: if he’s truly reformed. In the end, we can no more construct a future human life than reconstruct a human life that is no more.

In The Festival of Insignificance, the character Ramon compares ageing to joining the dismal army of the retired: his nonconformist remarks, which had used to keep him young, now … made him an uncontemporary character, a person not of our time, and thus old. I’m unsure whether ageing is viewed any better as the process of becoming uncontemporary. If a survey were done of average incomes, my income would count for what it is, as a piece of data in that calculation; my age likewise, as also the number of days holiday spent abroad in a year and the time I spend in traffic jams. All these things, for as long as I am alive, will count towards the calculation of statistics. But at what point do I, as an opinion-haver, cease to count? At what point do my remarks take on an uncontemporary character, maybe attributable to my lack of linear evolution?

A man’s uncontemporariness is not uncontemporary, for, if he lives, his remarks live with him and are, thus, contemporary. But, when he’s young, the uncontemporariness of his remarks is deduced and explained as being attributable to the young man’s age. And, later, when he ages, to such a degree as might be deemed sufficient, but for which there exists no objective, but only a subjective, standard, then his remarks once again assume the quality of being uncontemporary, and the deduction and attribution thereof are the same as when he was young.

That will be linear evolution, for what it’s worth.

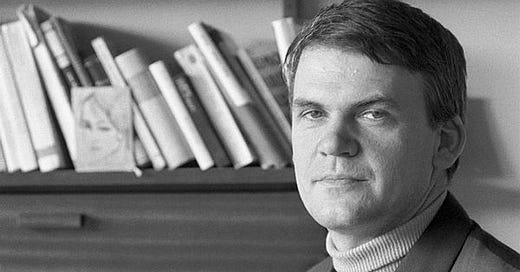

† Milan Kundera 1929-2023