On the common law and its relationship to morality

Courts must not become a device of the wealthy

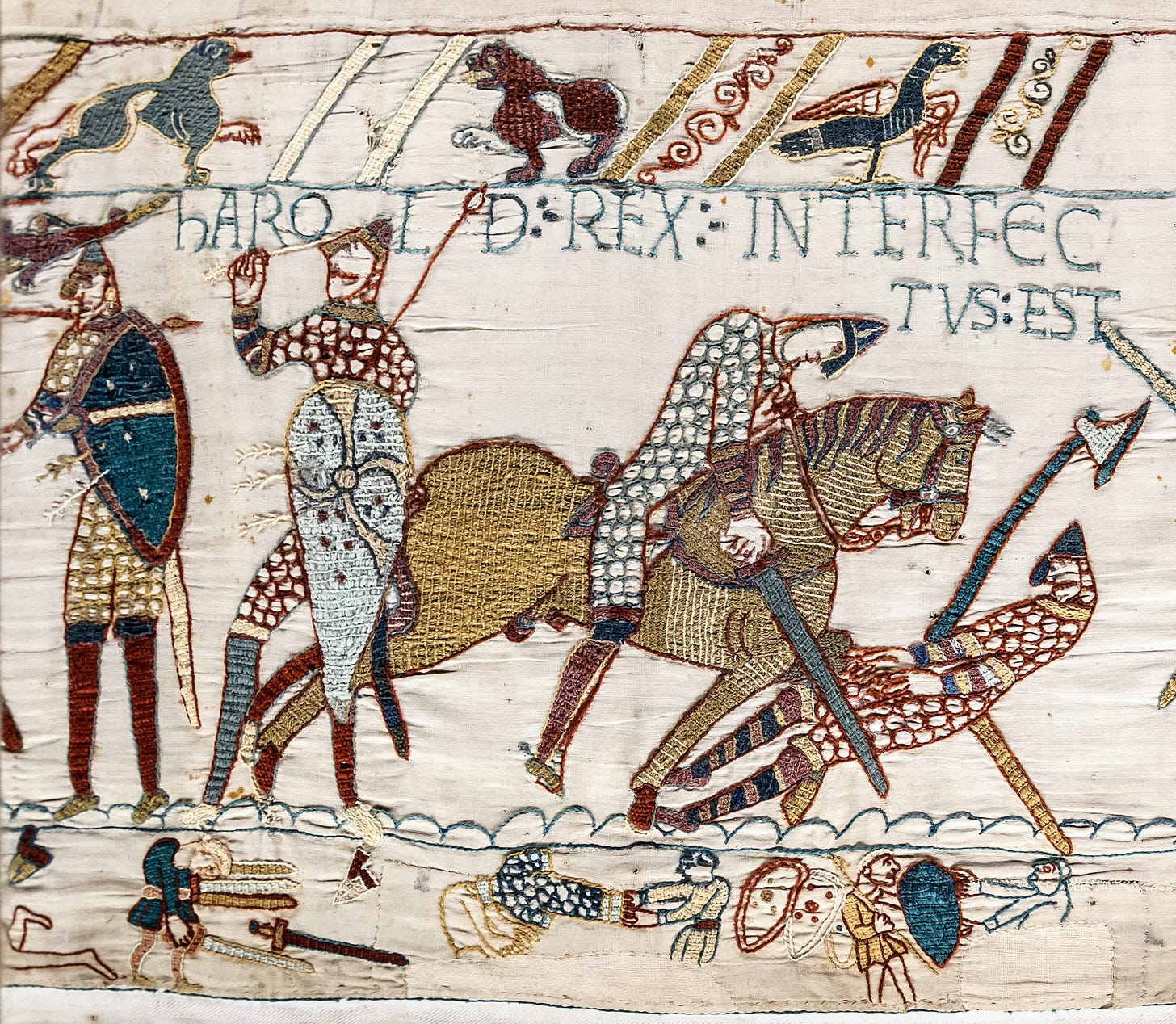

The Battle of Hastings was one in the eye for King Harold.

A verdict has been rendered in the court case against Donald Trump in New York. A verdict; not a final verdict. Out of a long-standing consideration of the notion that courts can get things wrong, the State of New York has, among its many legal traditions, some worthy of criticism (such as the Court of Surrogates) and some worthy of esteem (such as its separation of ecclesiastical and ordinary jurisdictions), one tradition of note, in form (if not in substance), in any jurisdiction that can rightly be defined as founded in what we call the rule of law: a system of appeals.

The rule of law is the principle that law can be relied upon. To do what is not always entirely clear, but the expression rule of law means nothing more and nothing less than that the law will operate in a manner that is lawful.

Some might argue that it means something more than that: it means that the law will operate in a manner in which it is expected to operate, and almost immediately, one arrives at a conundrum: the function of the law is to apportion rights and duties. Every right portends an equal and opposite obligation, if only an obligation of obeisance to the right. The rule of law therefore means that, provided our expectations are within the letter of the law, we should all have the same expectations, shouldn’t we? If that’s so, why do we need courts?

The State of New York is a jurisdiction of what we refer to as common law. Often inaccurately described as judge-made law, common law is not some legislative prerogative conferred upon the judiciary. It certainly involves the judiciary, on occasion at least, whose responsibility is not to make the common law but to find it.

In common law jurisdictions, such as the State of New York (and assuming the assimilation of law and equity in our 21st century, such as it was finalised in England in the 19th), the law stems from one of two places: there is the common law itself (and having just expounded on what it is not, I shall come back to explain what it actually is below); and there is legislation. Without too much controversy, what we can say is that legislation is legislature-made law. Made by parliament—in New York, the parliament, or congress, of the State of New York. In our modern theory, the legislature is separate from the judiciary (and, the third arm, the executive), the fundamental difference in roles being that the one makes laws, and the other applies them (with the executive administering the systems that the law institutes).

So, who makes the common law, and, if we know it’s not judge-made law, what exactly is it? The common law earned its name back in the years following the Norman Conquest of England. Pre-Conquest, the law in England had been a very different creature to what we now know as law: for a start, there was no true kingdom of England, it being still divided among various realms, like Northumberland, Wessex, Mercia and so on. Each small part had its own laws, which were created, applied and administered in a manner much more akin to governance as a whole, with the separate earldoms not yet operating on a strict separation-of-powers basis. After the Normans arrived, they were no longer administered by earls, but by counts, hence becoming counties, and no longer shires (although that word did get retained in the names of some of them, like Yorkshire, or Huntingdonshire). The shires were previously administered by reeves of the shires, shire reeves, or sheriffs as they came to be known. Once all England was ruled by a single monarch, these separate bodies of law around the country became unified in a system of law that was common to the whole country: the common law.

The reason why judges don’t make common law, but rather find it, is that common law and legislation are fundamentally opposite in how they operate: with legislation, parliament identifies a mischief, something that it wants to have regulated, usually by a government minister. The minister will craft a bill to be presented to the members of parliament in accordance with his administration’s policy. At this point, the executive and the legislature are closer than legal theorists might find comfortable, but legislation needs to come from somewhere. It can also come from other members of parliament, but politics has a large part to play in the statutes that make their way onto statute books, so it’s helpful to have a ruling majority, which means most of them are initiated by the executive.

However, even if it’s of interest and helpful, the court should not necessarily need to identify the mischief that impelled the legislation in the first place. Its task is to apply the law’s provisions as parliament promulgated them. All it need do is read the statute. With the common law, one is dealing with principles handed down (tradition) over centuries, which have been honed and shaped in relation to specific (and, by their very nature, unforeseeable) cases to which they have been applied.

What legislation does, therefore is set down in writing the rights and concomitant obligations that it wishes to regulate. I say wishes because that is all that legislation does: it wishes. And what it wishes is something that the courts must discern when a case founding on the legislation comes under their purview. The judge has to work out what it is that the legislation wants.

The common law, like legislation, is a pre-existing thing. There have been cases in which the common law was virtually summoned into being, but this rank disregard for tradition was always done in the highest of traditions, so the courts said, at least. Thus it is that baseball came to not constitute inter-State commerce in the US (whereas vaudeville did), and indeed that the law of contract came to hold such a prominent place in the law, pretty much at the invention of Lord Justice Coke (his ability to whip up eternal, immutable principles has been likened to that of a short-order chef to whip up a fried egg). While the process of divining the meaning of the common law and legislation seems retrospective in both cases, the judges need to determine the common law not on a retrospective, but on a prospective basis: they shape what the law means now and will mean henceforth and lay it down in precedent. Insofar, they must determine what the law has always been, and find that meaning, then apply it to the case before them. Legislation is interpreted according to what parliament meant (or cannot but have meant, if truth be told).

The reason why the common law and legislation are so fundamentally different is because the one encapsulates and guarantees rights and obligations that have existed for all time (hence Coke’s use of words such as eternal and immutable). The rights stand fast as fact: what the court must do is determine in how far the party’s right helps them in the case they have raised before it. In the case of legislation, the right they invoke is set forth in a statute and the court’s job this time is not to apply their case to the right, but to determine what right they even have, for that is ensconced in the language of the legislation.

The law is more or less divided down the middle into substance and procedure: substance tells you what your rights and obligations are; procedure tells you how you enforce them, and it is that second aspect that harkens back to the fact that all law does is to wish. For law is immobile and inanimate. Law will do nothing until someone does something with it. Above all, law will not enforce itself. Well, not entirely, anyway.

Let’s say you have a gripe against someone and you want to enforce your right and the other party says no. What do you do, aside from writing threatening letters? Well, ultimately, your rights are of no value to you until you raise a lawsuit, obtain satisfaction (don’t forget, you’re enforcing your rights—you will win, won’t you?), get final judgment, assuming the judgment at first instance is appealed, and then instruct enforcement, to force your opponent to do whatever he was refusing to do or pay compensation or whatever.

All of that court action rigmarole to actually utilise the right that you maintained all along was yours is called procedure. The charge for lodging the lawsuit, the time for written submissions, what motions can be made, the timetable for the case, and so on. It’s all procedure. In fact it’s only once you emerge from all that procedure that your substantive right has any value to you at all. As a legal right, that is.

Now, this may all sound fairly obvious, but I can assure you that, even in a litigious society like the United States, there are vastly more infringements of rights and obligations as between potential litigants in court cases across that nation than there are court cases with a view to crystallising those rights and obligations, giving them substance. The disputes that go to court are but a minute fraction of the disputes that could go to court. So why don’t arguments get litigated?

One reason why people don’t litigate is because they don’t need to. The mere existence of the body of law and the mere prospect of litigation is, in the vast majority of cases, enough to persuade those who have transgressed the rights of another (be it a civil party or, in a criminal context, the State) to admit to their fault. While the precise effect that the law’s mere existence has on a given individual may vary (from recognition of their civic duty, to fear of the consequences of transgression, whether through monetary penalty, physical punishment, or social sanctions), the reason why so many disputes get settled before going to court is because of the moral imperatives that prevail upon members of society. In other words, many disputes are settled satisfactorily not on legal considerations but on moral considerations.

We learn in the realm of jurisprudence that morality and law are opposites; not so—in fact, in practice, the one is a major part of how the other works. By the same token, a legal system that operates in a manner generally viewed as unconscionable may well be successfully applied in terms of the rule of law, but will lack in moral endorsement from those who are subject to its strictures. The reason so many disagreements in a country like the US get settled with the other party making extrajudicial amends is because his conscience tells him to.

This moral restraint is especially present for offences against the common law: failure to honour one’s contract, for instance; causing harm to another, and making good the loss (unless an insurance company’s involved, that is). The principles alluded to by Coke are precisely so eternal and immutable because they have governed how men and women interact since the dawn of time (or, as Coke would have it, how men and women should interact). That’s why the common law isn’t judge-made, but judge-stated. That’s if they state it; because, whether of the common law or of legislation, no judge will pronounce a right or obligation as existing and applying to a given case unless he or she is asked to.

As we have seen, the result of this is that, for the most part, relations to our fellow citizens are governed not by law, as such, but by our moral rectitude. If there were to be less moral rectitude, there might be more law, but law isn’t simply an option to rectitude, because rectitude costs nothing, whereas law, and its procedures, are very expensive. So expensive, in fact, that the cost of attaining recognition of the right that is legally decreed to belong to you, right here, in this instant, can be so steep as to dissuade you from even seeking its substantive confirmation. You may as well renounce it.

Mr Trump’s New York case is viewed by some as him placing himself above the law, saying that he can do as he wishes and no one can touch him. And the current verdict is seen as vindicating the notion that no one is above the law. I don’t think that that analysis is quite correct, however. The rule of law, and the US Constitution’s principle of due process (which is part of its law), already establish the principle that nobody is above the law. Nobody has contested that proposition, not even Mr Trump’s counsel.

However, in his financial dealing, Mr Trump has displayed conduct that paid scant heed to the moral imperatives that maintain in check the actions of most of America’s citizens. Most people in the US (this is no blind assertion, simply an extrapolation of the huge imbalance alluded to above between total disagreements and total lawsuits) feel themselves bound by their consciences to their fellow citizens and, in a free and open society such as America’s is, and which it sorely wishes to remain, the underlying moral obligation to the letter of the law, especially the common law, is the prime factor that even allows that sort of society to function, without it becoming an oligarchy or police state. It rests upon reliance: reliance in the rule of law as being the law as promulgated; reliance in the fair and just application of that law by the institutions to whom it falls to apply it, whether on a petition by the State or a civil party; and, lastly and by far most importantly, reliance on the moral imperatives to respect that law notwithstanding the absence of procedures seeking to enforce it.

Where the moral imperative wanes to a level that manifests itself in egregious disregard for the law, and the law’s enforcement is seen to be lacking in its vigour, then one or more of a variety of conclusions can be drawn:

That parties (including the State) are indolent in enforcing rights. This may never be the case. The State’s prime duty is to establish rightful reliance by the people on the law. That is the fundament of the rule of law. A state that fails in that regard may vaunt a rule of law, but that is a worthless assertion if its law fails to meet commonly held standards of justice.

That parties cannot afford to enforce rights and exact obligations. Whilst justice cannot operate as a free service (although, one might ask: why not? The fee for lodging an action doesn’t even look at the procedural expense of operating the court system on behalf of litigants, anyway), it must be the State’s duty to ensure that access to justice is, insofar as is humanly feasible, guaranteed to all those on whom rights and obligations are bestowed under the State’s law. Otherwise, courts become a tool only at the disposal of a select few.

That the law begins to be seen not as a structure overarching society generally but as a game. Of course, the practice of law is festooned with tactics and strategies. That’s because the eternal, immutable rights that people enjoy need to be enforced via made-up, essentially arbitrary rules and regulations intended to secure, not the rights and obligations in question, but rather the smooth running of the courts administration. It is perfectly possible for a society to be entirely law-abiding and for its courts to be rendered redundant. This utopia is still far off; yet, to view the law as a game is to view it as a set of soulless rules that are there to be circumvented by loopholes. The players constantly evoke its legality as a due and proper standard for their actions; transgression and criminality get reduced to the crossing of arbitrary lines; in and of itself, this has the effect of rendering the society governed by such game rules more litigious in nature (a coach driver once told me that in Germany they drive according to the rules, in Italy they drive according to the traffic, and have about the same numbers of accidents). Ultimately, this has the effect that rights and obligations previously vested in all and sundry by common tradition, evidence of whose substantive existence rarely called for any enforcement at law, are increasingly only able to be relied upon by those who are in fact prepared, and have the wherewithal, to file a court action, not to find a right and not even to establish a right, but, far more, to stake a claim to a right, as if it were some flag on a farmstead in 19th century Oklahoma.

It is a widely held truth that the candidate in an election who can raise the most money to support their campaign will always win. The danger is that justice devolves to a point where the litigant who can raise the most money to back their litigation will also always win. In many places, and not just the US, insofar as any law can favour or disfavour any particular group of persons, they can be sure of having a rule of law that can be relied upon—again, to do what is not always entirely clear. But, if the ability to lay claim to the rights conferred under that rule of law is to depend on something as crass as money—the greatest social differentiator ever conceived of by man—what cannot be relied on is the law’s ability to act as a cohesive cupola in which the citizenry can be assured of their rights under the law, even absent its enforcement, or, perchance, under the menace of precisely that.

First, Graham, thank you for correctly spelling prerogative. This is anther word that can get my hackles up, too many Americans both pronounce and spell it as peroagative. I like your examples of Common Law. The one error I detected is in stating trump and his lawyers have not disputed that he is not above the law. In fact from an American perspective that is the most important point in all thee legal cases. Trump has demanded absolute immunity for every crime he has committed since he declared his candidacy. And his lawyers have backed him up, stating before the Supreme Court that Trump could legally order our military to assassinate his political opponent with absolute impunity. He considers himself equivalent to his hero Vladimir Putin.

The recent trial in New York was another example in most democracies (and yes I know that is he wrong term) cooking the books is illegal for any reason. New York law has codified this.