“You should write a blog,” someone once told me. For a long time, I ignored her, and others. I didn’t even know what a blog was. Where to get one published. I had no aspiration to be a writer, and, to be frank, still don’t. If it happens, it happens.

In the end, I asked Dee, and Dee, who hosts my website, suggested a certain portal, which, try as I could, never really worked for me and cost me 2.99 a month for a year. When I finally put this blog up on Substack, the someone who’d once told me to write it said I was doing it wrong. She told me previously I’d been doing it wrong, and now I was doing it wrong again. I replied that I wasn’t writing the blog for her; I was writing it for me. And, if she liked what she read, she could sign up and, if she didn’t, she didn’t have to.

And, just like I’d said to that someone, because I am writing the blog for me, and because I don’t charge money to me for being me, then I don’t charge money for people who want to read me. And those who don’t, don’t need to.

Anyone who asks me, I will tell them what I mean by what I write. Occasionally, I read back over stuff I wrote before and cringe. Or take a new view. When I studied Konstantin Stanislawski as part of my acting studies, what struck me as I progressed through his books An Actor Prepares, Building A Character and Building a Role, is that there were aspects on which the author contradicted what he’d said in previous passages. It’s generally accepted that, while he remained constant in his development of emotion memory and magic if as concepts, other ideas waxed and waned as he himself developed in his ideas of realistic theatre. This blog has to be viewed in a similar vein. Theatre, like life, is work in progress, until it ends.

The someone unsubscribed; I think it was because she didn’t get what I meant, and didn’t want to ask me. She knew, without knowing. Like reading someone’s diary and expecting it all to flow like a novel, to have a beginning a middle and an end. Heavens—it’s a diary, and they don’t have ends; they just end.

My purpose in recounting this to you is in order to broach the idea that one can actually be eccentric and not unusual. You can actually be unconventional simply by refusing to follow a conventional way of thinking. The fifth wheel, even. The one who always gets things wrong. A clod.

When I was 11, I had my first Latin lesson and, to be honest, was assigned the very first homework assignment of my entire life. Mr Jones was the master, and he was a fearsome hulk of a man who, even if you’d been a foot taller than his six feet plus, would have loomed over you. He’d attended Long Eaton Grammar School in the English Midlands, and would boast, with a smile, that he’d been at Eaton.

The preparation, or prep as it was called, was done, submitted and marked. I had done as I’d thought I was required to do, which was write out the present tense of the first-conjugation verb amare: amo, amas, amat, amamus, amatis, amant. I’d misunderstood. Jones was not angry with me, but he posed me a question: did I believe that I’d done the correct homework and that every other boy in the class had done the wrong one? Truth is, I can recite that verb still to this day, as well as fifth-declension nouns like spes—hope; and I did attain an A-grade in Latin at ‘O’-level. But, in that moment, I was abashed and ashamed, and Jones gently added, “If you could do the correct exercise tonight, that will be fine.”

Arthur Evan Jones was one of the most feared, the most upright, the most fair, the most honourable, the most remembered men from my school days, and we corresponded occasionally even after we’d both moved on from the school, to which his own connection was abruptly severed after a coarse remark was made at his expense at a reunion gathering. It must have been mightily coarse, for Jones was very thick skinned. But he could not bear bad manners.

However, what I more than anything remember from this Latin prep incident was how he’d phrased the question. Did I think I was right and everyone else was wrong? Yes; at the time I did the prep, while the assignment was not what I then thought it was and partly because I didn’t know what the other boys were doing for their prep, I thought I was doing the right prep. And no amount of correcting things afterwards can disabuse me of that belief in the moment itself. I was mistaken, but I wasn’t wrong.

Moreover, it is possible to be right when all around you are wrong, or even mistaken; to be a lone voice. A. E. Jones never told me I was wrong; he told me to think about whether I was wrong or not, and between the two is a world of difference. Because the exhortation to question one’s own rightness is likewise an exhortation to question whether others truly are wrong. The things that teachers teach are not always what’s on the academic syllabus, even if they’re on life’s. Prep for life.

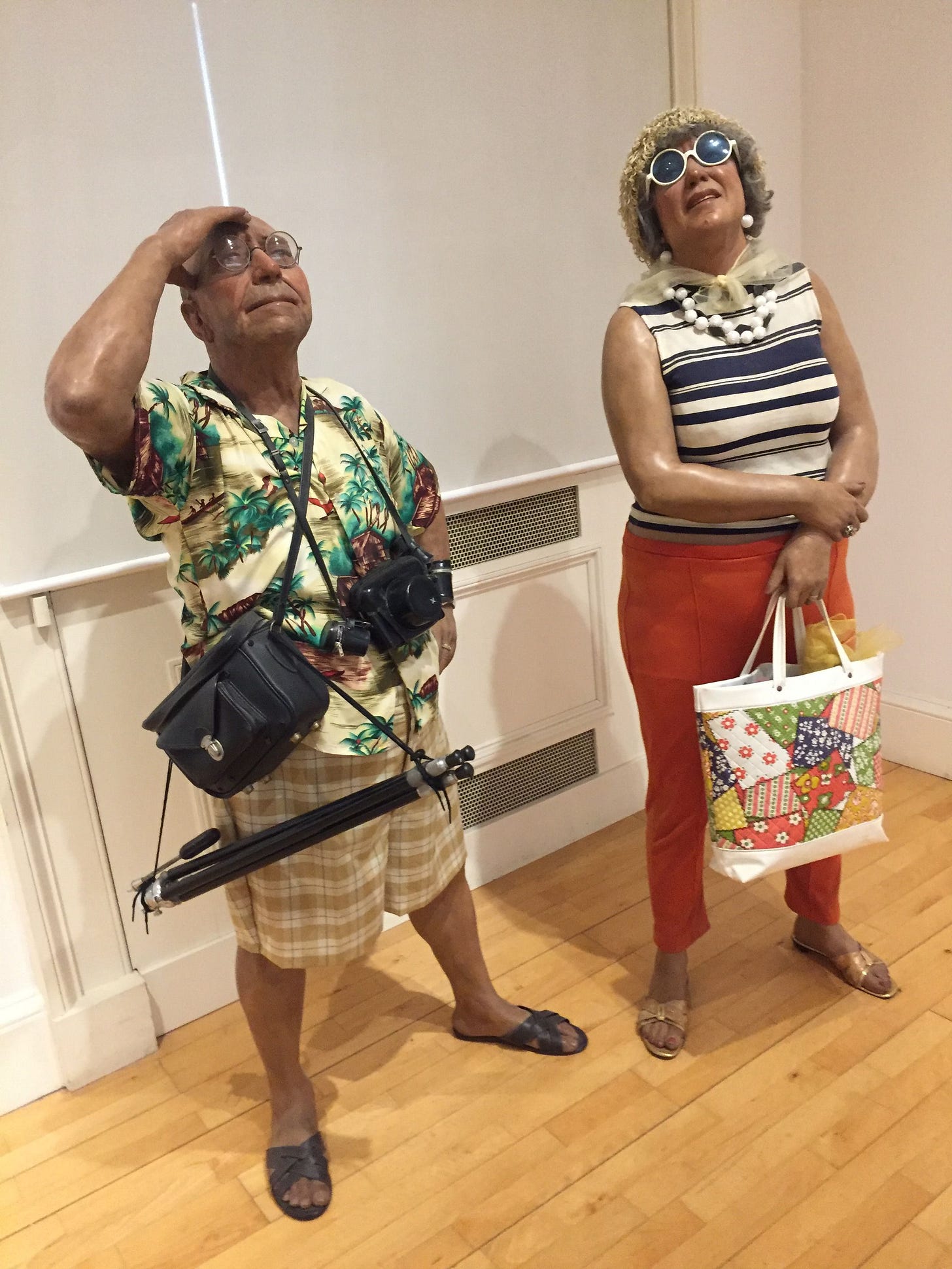

Later on, when I was at university in Edinburgh, I would occasionally pop and see my great-uncle and his boyfriend, who lived in an elegant basement flat in the district of Inverleith, a pensioner’s free bus-pass ride, as it happens, from the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art. Jim, my great-uncle’s other half (who bore a striking resemblance to the actor Terry-Thomas, and spoke in a remarkably similar manner, but with an east-windy, west-endy Edinburgh accent), recounted to me that they’d gone, the two of them, up to the art gallery to see a recent acquisition that had hit The Scotsman’s headlines in this tourist-infested town of ours: Duane Hanson’s Tourists. Here they are:

Jim was a man who’d worked at the British Linen Bank in George Street, just along from the eponymous statue of George IV and the famous wine importers Justerini & Brooks, who blended whisky and marketed it as J&B’s. He had, for the bulk of his career, worn a stiff wing collar within the hallowed halls of the bank institution and harboured little regard for the American and other tourists who clogged up his thoroughfares (note—his), but otherwise had a delectable taste in antiques, which gracefully festooned their residence. He found this plastic model of gawping Yanks hilarious, and all Edinburgh was talking about them at the time.

Hanson himself had an interesting career, in which he couldn’t really decide whether he preferred Florida or New York, and shuttled between the two a little bit. His early work was highly violent in nature and intended as a social comment, which it was (in one piece, a policeman is beating a Black man and another Black man is beating a policeman). He was a great admirer of Millet, as am I:

Millet’s Gleaners

In 1857, Jean-François Millet unveiled his work The Gleaners, depicting three women scavenging a wheat field for whatever was of use that the harvesters had left behind. It is bucolic, rustic, redolent of a bygone age, and it caused outrage when the upper echelons of society saw it.

But Tourists is in a more serene mood, and, while still social comment, it’s less embittered and more playful. I worked in tourism (hence Jim’s jibes at me) and I can assure the memory of Mr Hanson that tourists have moved on from those times: the shirt pattern here is veritably sober by today’s standards. The footwear eminently sensible (what: no sneakers???) and the camera equipment is all gone. Like mother’s cine camera before it, the single-lens reflex (or SLR) camera is a museum piece. I suspect that, if Hanson were alive today, he’d have shown them posing madly with a selfie stick and iPhone, but that would be a comment on today’s tourists and not those of 1980.

But there’s something else in this installation that does not warrant any jibes or hilarity: these tourists are not vacant and detached. They are looking. Upwards. Very few tourists raise their gaze above eye level. It’s a fact. And it’s a tour guide’s trick: to reveal to the visitor something that is right before their eyes, or would be if they raised their gaze by about six feet. And that’s about the distance that these tourists are raising their gaze. What are they looking at? An architectural detail on some ancient palace? A parachutist? An aeroplane being flown into a New York skyscraper? Whatever it is, the gentleman is not reaching for his camera to capture it. Why not? Is whatever they see stunning them into inaction? It’s interesting enough for both him and her to be enraptured by it, but not enough to photograph it? Perhaps it’s the ghost of Jim Hutchison. Perhaps I’m wrong and he and the rest of Edinburgh are right.

I hesitate to label Tourists as a lampoon, pastiche or parody. It’s in fact a representation, and a fairly accurate one at that. Jim and my great uncle holidayed in Italy and never had a camera with them, instead buying fold-out postcards as a reminder of where they’d been—a souvenir. But they could remember every aspect of where they’d been and didn’t simply look for Kodak moment photo opportunities the whole time they were away on holiday—to relax. Kodak—there’s a word you don’t hear often these days.

Someone was a kind person, who wanted to encourage me to explore writing. But, because I didn’t accept her coaching, and had my own reasons for writing, she simply severed the friendship. I never did ask her where she thought I should go with my writing; and she never did ask me where I wanted to go with my writing. Perhaps friendship is overstating it, therefore. I hope she is happier without my … whatever it was, but I don’t know if I am without hers; because she disagreed with me, and, like some, I thrive best with those who disagree. A disagreement is an attraction—don’t opposites attract? But many folk find it more agreeable to be with those who agree with them.

The problem is people who agree for a reason you’re unaware of.

If you agree with this, please like it. That way, our whatever it is will grow closer.

Good for you, Graham, to admit you write for yourself. Otherwise you are writing pablum for the masses to ingest. As you are aware I do not always agree with you, but I always enjoy your perspective,