In Owen McCafferty’s play Quietly, two men have arranged to meet in a Belfast bar. Jimmy and Ian are 52 years of age. Ian wants to say, “Sorry.” He killed Jimmy’s father in that bar, with a bomb, when he was 16.

I’m trying to imagine a meeting between a Ukrainian and a Russian, 36 years from now. How easily two men could meet in a Bucha bar — the bar where relatives of the one had stood as the other manned the tank that destroyed the building they were in and all those who were in it.

I am trying to imagine a tank rolling into Lancaster county in Pennsylvania, where the Mennonites and the Amish live by a doctrine of non-retaliation and of non-defence, stopping and rotating its turret before taking aim at the simple wooden houses of the people who live there and whose families have lived there for over 400 years. And I am trying to imagine their acquiescence in the horror inflicted upon them and their brethren folk.

And I can’t.

It’s not that I don’t believe in the ability of Mennonites to forgive those who wreak destruction upon them; I do. I do believe in that. Like I believe in God. But I cannot imagine God; and I cannot imagine their ability to forgive, even if I believe in its potential to exist. For, both God and the forgiveness of horror are ineffable.

Ian and Jimmy meet in an effort of reconciliation, between the republican who lost his father in a bomb attack in which the loyalist threw the bomb. And they succeed; and they fail.

Because what Jimmy lost was not his father. It was his mother. Who lived through the pain and the illnesses and the cancer without her man beside her; and that was the burden that Ian imposed on Jimmy.

What Jimmy and Ian wanted to try to reconcile themselves to wasn’t even what they ultimately realised they needed to reconcile themselves to.

“After all this time, I can’t hear my father’s voice any more – it’s gone from my head; that time has passed. I can still hear my mother’s, though. There’s nothing you can do about that, nothing you can say, nothing you can do,” says Jimmy.

“I was sixteen years of age, I’m trying to do the right thing.”

“I know,” replies Jimmy. “When the twenty thousand of you marched by the top of our street, I screamed at the top of my voice: ‘F***ing Orange b*****s - f***ing Orange b*****s. I was sixteen as well – I know what world you lived in.”

Ian stands up and offers Jimmy his hand. Jimmy stands. They shake hands.

“Don’t ever come back here.”

Ian exits.

I’m trying to imagine a bar in Bucha. Thirty-six years from now. Two men, one a Russian come to apologise; one a Ukrainian who lost his family in an attack of which the Russian was the author.

And I can’t.

It’s not that I don’t believe in the abilities of Ukrainians to forgive those who wreak destruction upon them; I do. I do believe in that. Like I believe in God. But I cannot imagine God; and I cannot imagine the Russians’ contrition at what they have wrought in Ukraine, even if I believe in its potential to exist. For the destruction, the ability to forgive it, the potential for contrition: all three are ineffable.

Reconciliation is fruitless, unless the parties who want to reconcile know what it is they need to reconcile.

I’m trying to imagine a bar in Bucha. Three hundred and sixty years from now…

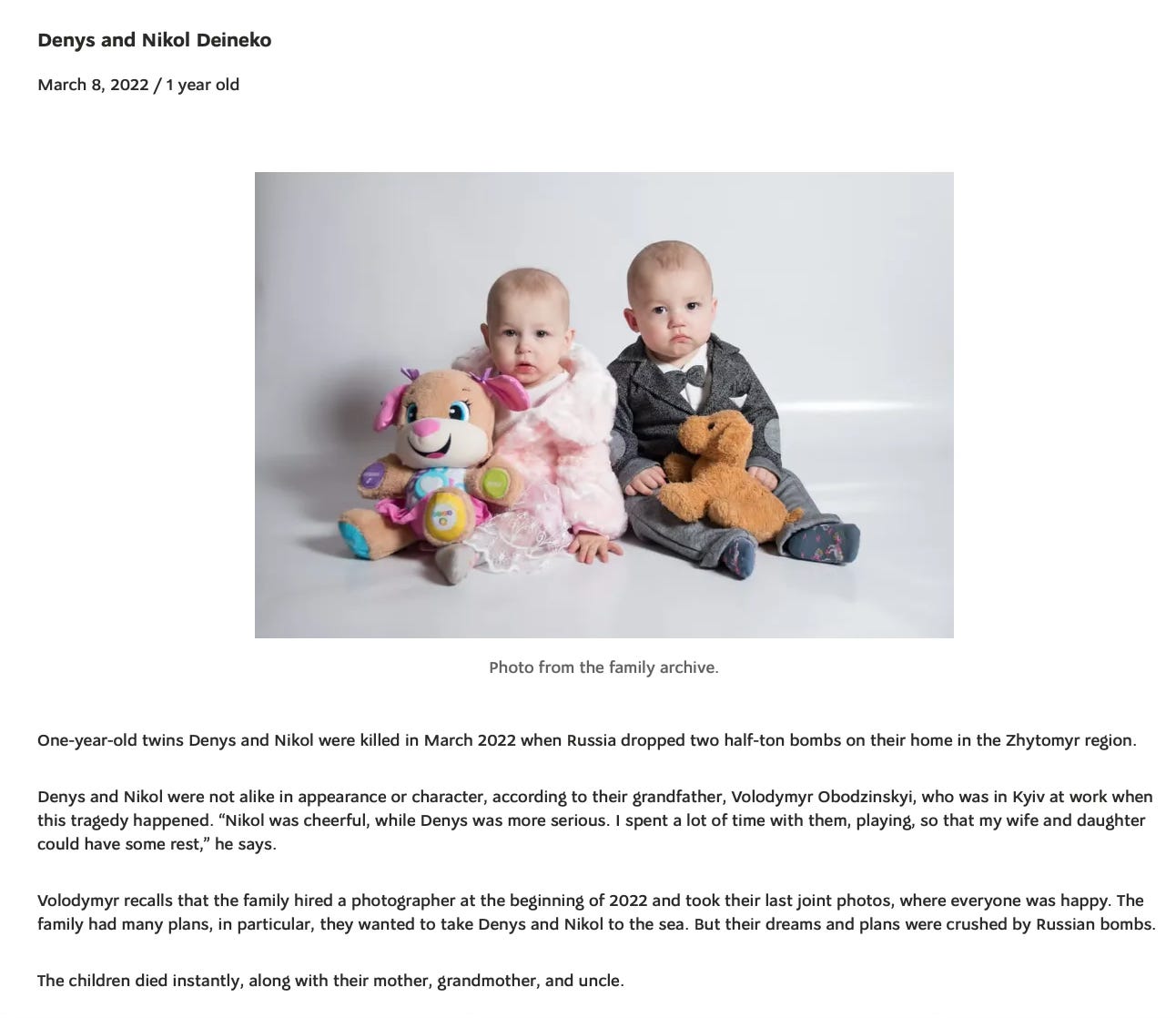

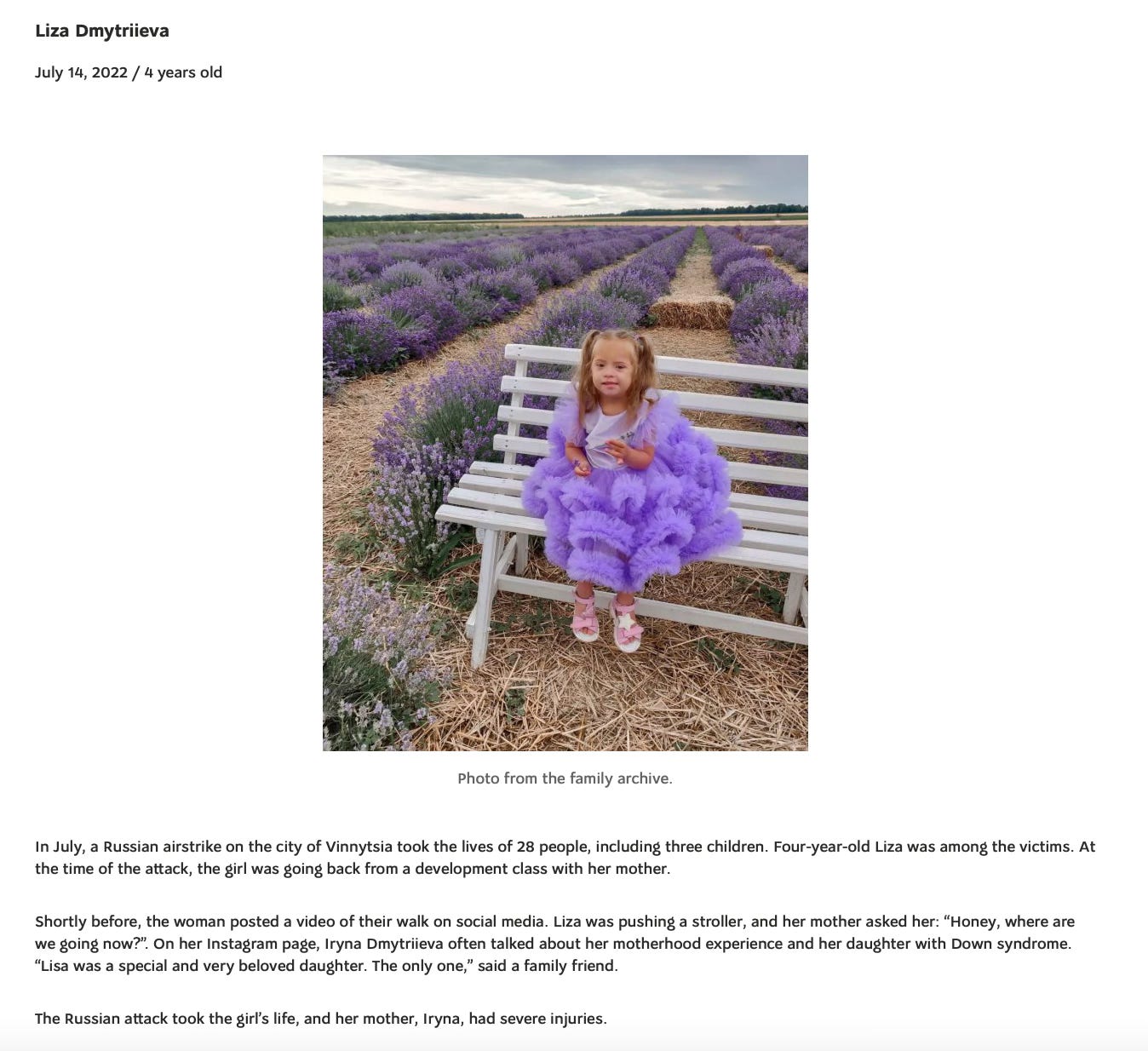

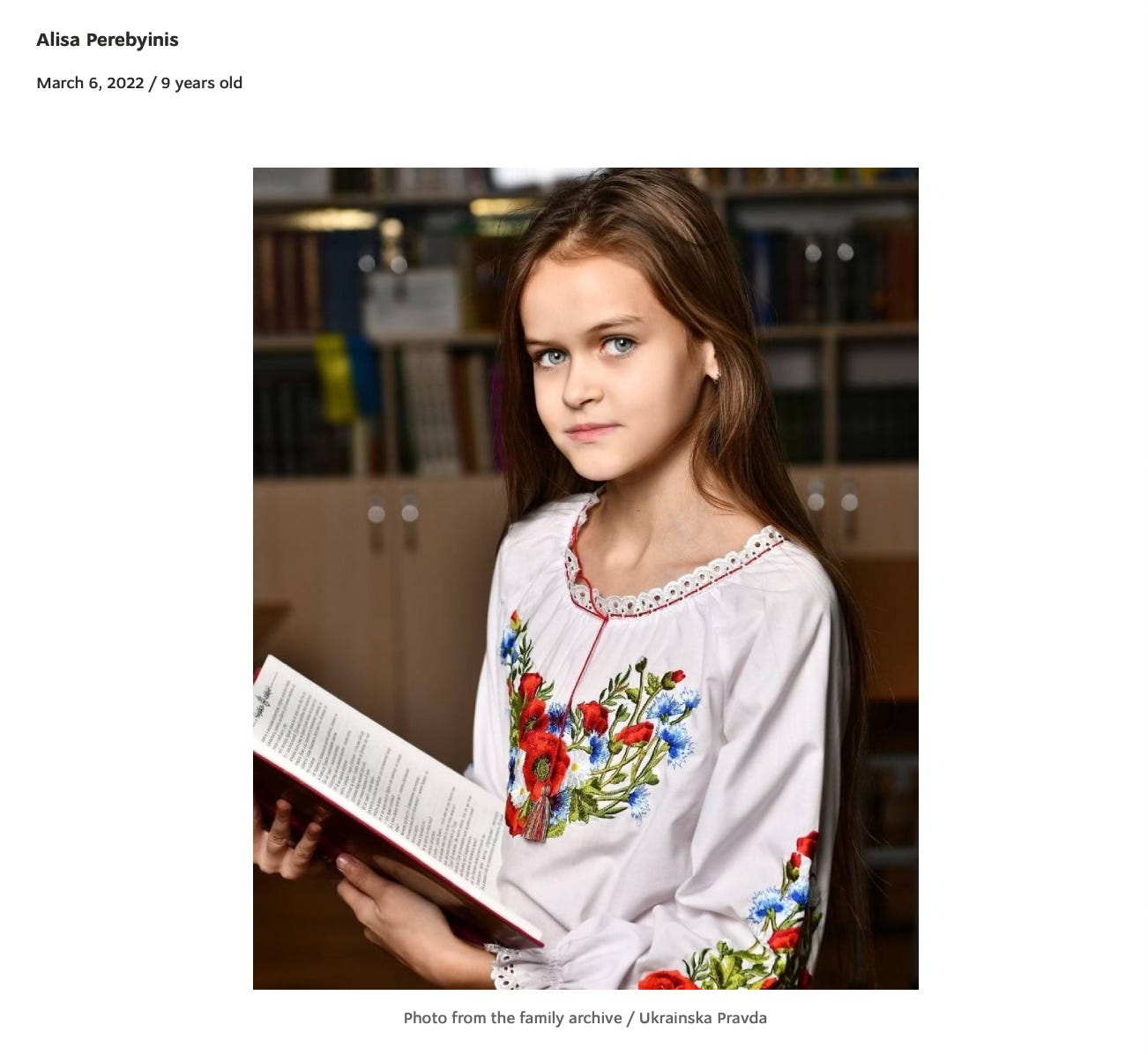

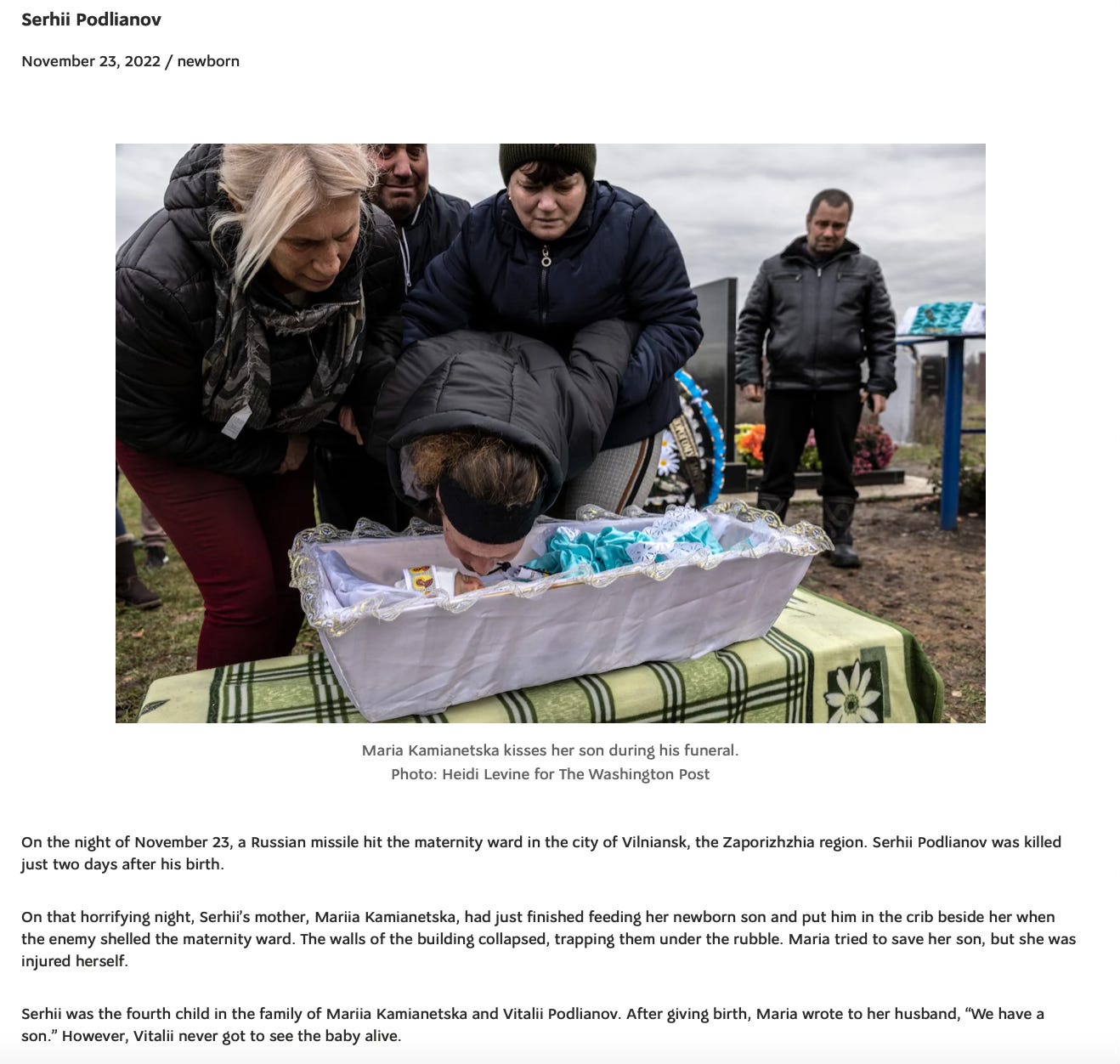

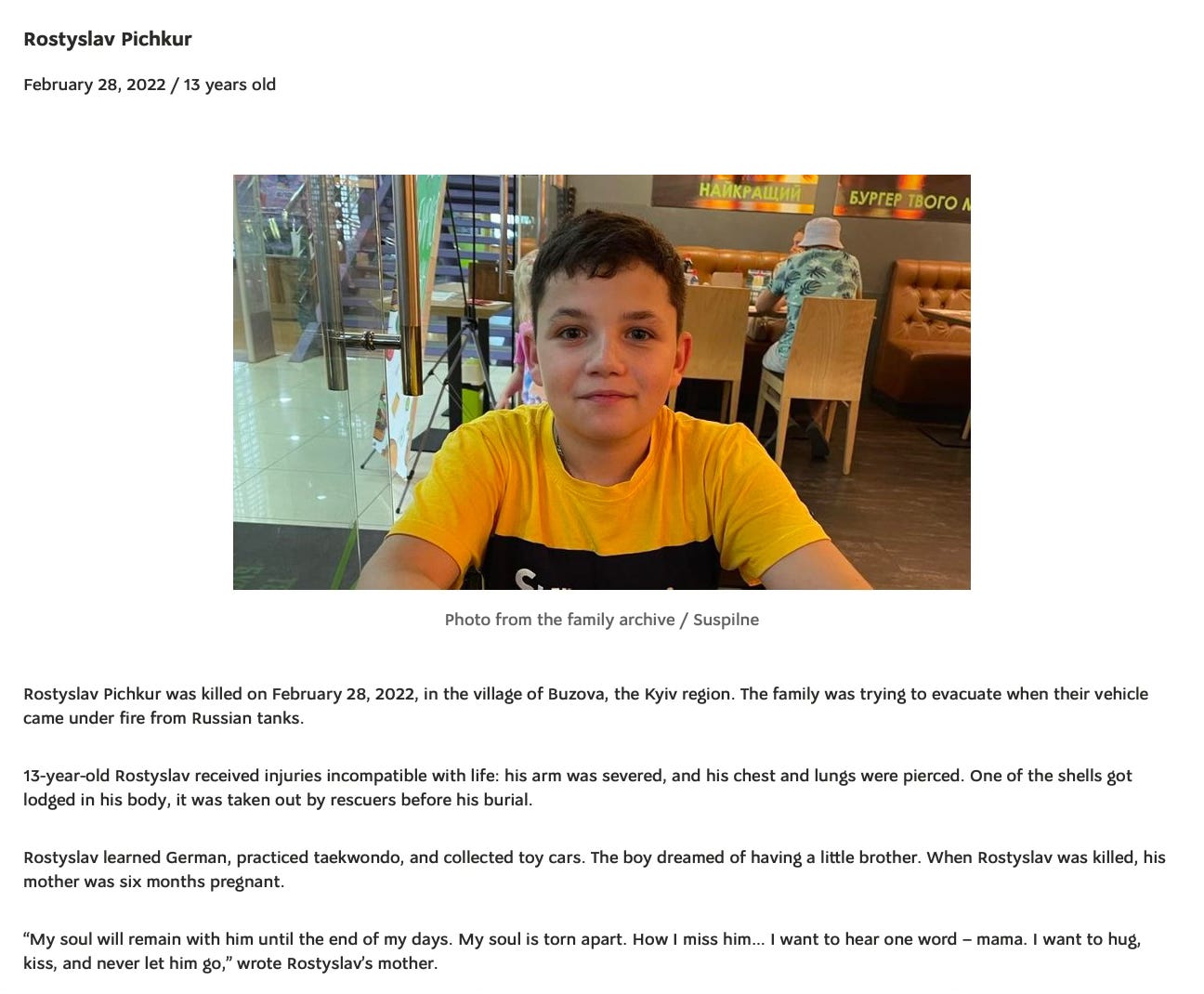

Acknowledgements to the website https://war.ukraine.ua/articles/ukrainian-children-killed-by-russia/. In respectful memory.

Compelling questions of forgiveness. I keep thinking of Tutu and Mandela's Truth and Reconciliation Commission in post-apartheid South Africa. Tutu says that forgiveness isn't even really altruistic: "If you can find it in yourself to forgive, then you are no longer chained to the perpetrator." I'm not coming down on one side of Ukrainians forgiving Russia or not; but one of my favorite glimmers of protest against Putin is the hair color of one of the Atlanta Symphony's violinists: blue on one side and her natural blonde on the other, the flag of her native Ukraine, a visual reminder that this war is still going on while Nero fiddles.