A gander is a male goose, and the saying implies that how you dress a goose for the dinner table is pretty much how you would dress a gander for the dinner table. Prandial sex equality, if you like.

So, why do we so regularly serve up different sauces?

Image: Liberty Bell, Philadelphia, USA. Public domain.

If I said that Chechnya passed me by without much notice, would that shock you? The Maidan Revolution—barely remarked upon it. The Russian occupation of Crimea—wasn’t there once a war there? I’m sure there will be a conflict somewhere of which I know or understand little (I’m learning all the time: the mafia’s hold over the Italian food industry; drug running and dead actors in South Korea; local atrocities across the United States, from its streets to its courtrooms). How much do I need to know in order to praise or condemn? How much to say nothing? How many other opinions do I need to know to formulate my own? And does the goose always get the same sauce as the gander?

When Russia invaded Ukraine, some said Ukraine deserved it. Some said NATO deserved it, and I needed to think about that. China didn’t say that much; Britain said a great deal. The US said one thing and then has started to say different things, because the piecemeal method they chose to feed Ukraine the means to win hasn’t resulted in a blitzkrieg-style outright victory. Question is whether it was ever intended to.

If I were a betting man, I would always, of course, try to back the winning horse, and the great thing with wars, unlike horse races, is that you can change sides halfway through, just like Italy did. You can even back the losing side and still come out a winner, or try to, like collaborators do. But, if you’re not a betting man or woman, you have the luxury of observing from afar the pros and the cons of a conflict’s belligerents: deciding with equanimity which you feel is the worthier cause. You make your own sauce, and you apply it to goose and gander alike; isn’t that so?

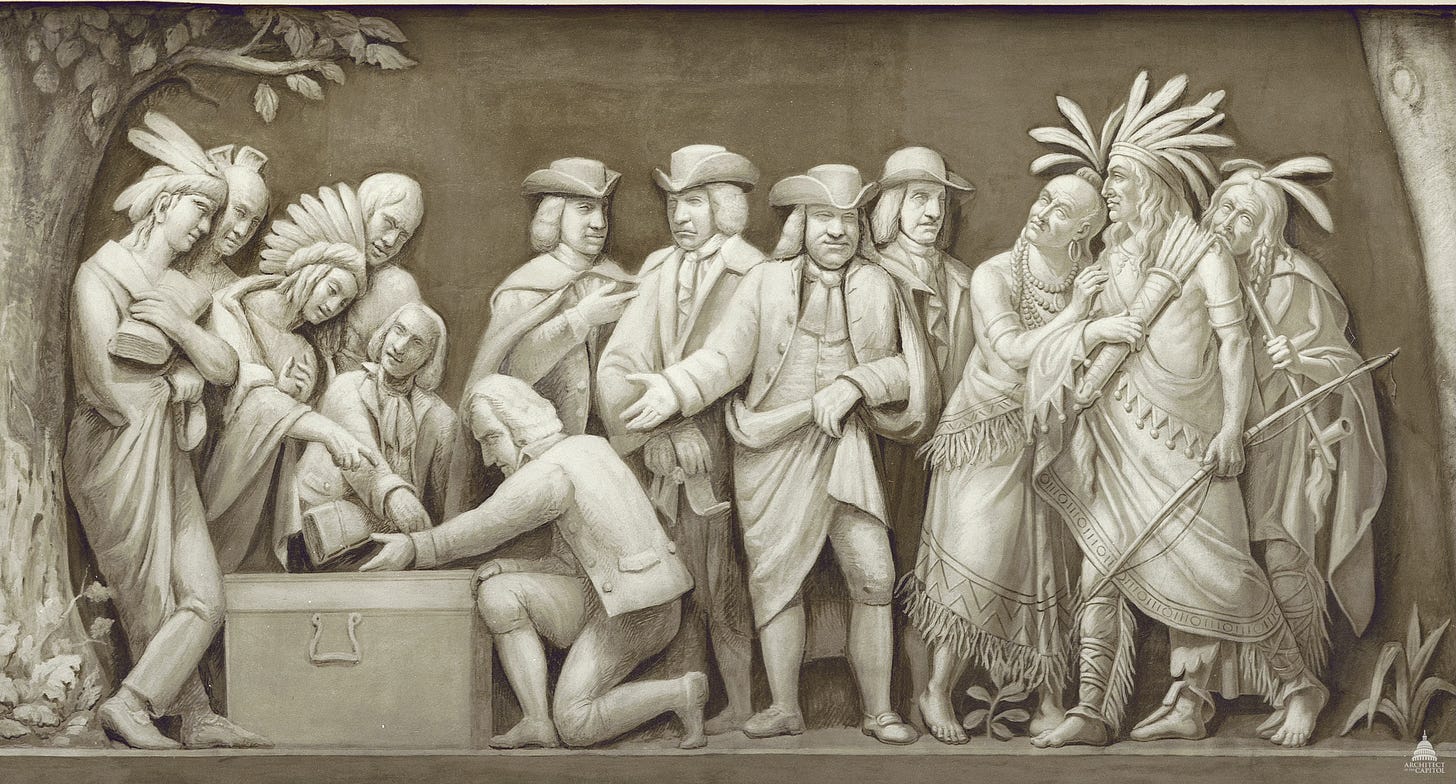

I have visited Philadelphia in its sticky, sweltering, summer heat and viewed the cracked Liberty Bell, beloved of Sousa and Python. I have viewed the State House where the Declaration of Independence was signed, and read of the “founding fathers”, the men whose audacity, bravery, backbone and brilliance resulted in the establishment of the most powerful nation on Earth. At the Capitol in Washington, D.C., is a bas-relief of William Penn sealing a pact with First-Nation tribesmen in Pennsylvania—the wooded idyll of Penn—though, whatever idyll was thereby established to the contentment of coloniser and indigenous inhabitant in the moment thus depicted, that contentment would not be felt in uniform manner across the breadth of what would become the United States.

I so often hear those words “We, the people” and the phrase “the founding fathers”, and I find it hard to appreciate how today’s Americans relate to these terms. They are cited by both sides of the political divide as a clarion call for unity and pride. And yet the founding of America is seen very much in the mould of a people rebuffing the ignominy inflicted upon it by an extraneous, foreign power, and subsequently opening its doors to welcome the downtrodden and destitute of Europe with graciously extended hospitality. It’s a view. It’s a view I have seen at the State House, at Ellis Island and Washington, D.C.,’s National Archives.

Elsewhere in the world, imperial powers are also resisted. The imperialism of Russia is braved in Ukraine, feared in the Caucasian republics and, increasingly, snubbed in Finland and other parts Scandinavian. The Taiwanese are ill at ease with China’s rattling of sabres, and even little Guyana needs more than indignation if it’s to repel dictatorial Venezuela. In all of these conflict zones and more, what is the principle that forms the principal ingredient in the sauce that flavours the meat of the matter?

Do you look to the irredentist claim and assess its historical virtue? Do you then arrive at different conclusions for different situations, allotting them something like atomic weights, which ensure they always float into their appropriate sector on your periodic table of elementary logic—hydrogen safely top left, helium ever top right? Or do you invent isotopes, which sneak in among your noble gases, even if they’re just hot air? Dependent on past acquiescences, past treaties, past victories, skin colours and languages, personal interests, national biases? What is, then, permanence?

Workers who are granted an annual outing to the seaside may look forward with relish to a day at Bangor, Bognor or Blackpool; but their employer will remind them sternly that this year’s outing is only grace and favour, and that it establishes no rights for the future. How, then, does management prevent a feeling of entitlement arising among the workforce? In short, it doesn’t: it simply disappoints when it next year says, “We changed our minds.”

When I look at the USA, at how its colonists repulsed the imperial power of Great Britain and declared that all men are free, thereupon founding, as fathers, the great United States, and I then see how, within a hundred years, they had split on a matter of principle and gone to war over that principle and resolved their differences in principle but failed in the ensuing hundred years to apply wholesale the very principle on which they’d fought and on which their nation was founded by their fathers, it is disdain I risk incurring at the Americans’ address, and it is praise I similarly risk incurring at the address of Zimbabweans, South Africans and Ukrainians.

Upon the retaliatory incursion against Hamas into the Gaza Strip, I was in my naivety taken aback by the sudden wave of support expressed for the Israeli state by those who had pinned their pro-Ukrainian colours to their masts. Prior to Russia’s invasion, the kind of terrorist organisation that precipitated Israel’s actions was absent in Ukraine. Or was it? The Russians would have it that the Azov Battalion was nothing more than a right-wing organisation of Nazi hoodlums, which was threatening and attacking its Russian-speaking compatriots in the people’s republics of Donetsk and Luhansk. And that the resistance, however weak-willed, put up by the Ukrainian army in the years between 2014 and 2022 was likewise a blight on peaceable life in the Donbas. Nonetheless, a wave of support arose for Ukraine and its defence of its borders, against the invader from the east.

In the Gaza Strip, the invader from the east has been hailed as righteous by the self-same body of opinion that denounced Russia against Ukraine. And, whatever the criterion is for marrying the support of Ukraine with support for Israel in some sort of fusion cuisine, it is not an ingredient in my own sauce for this goose and this gander, which tends to leave out any element akin to bloodshed. Goose is not black pudding.

If a powerful nation is plainly wrong to attack a weaker people, wantonly and without consideration of its ability to defend itself (I repeat, if), then the Israeli army is as culpable in its dealing with the ordinary population of the Gaza Strip as Hamas was in its dealing with the ordinary folk of Israel; there can be no question about Ukraine’s right to raise a defence against the attacks from Russia, unless, that is, like Russia, you tend to the view that Ukraine has no legitimacy as a nation state. Does the Gaza Strip?

And the founding fathers can only be looked to as the cornerstone of the United States provided one holds the swath of North America that is today that nation (with Canada, those nations; I shall gird my loins for Central and South America another day) to squarely fall under the terra nullius principle of non-occupancy ante bellum. It is a stance that must then stretch to belief in the honour in which the United States has held the treaties it forged with the indigenous owner-occupiers of its territory, as also in the fairness and equanimity with which it has dealt with its liberated slave workers in the years since its Civil War. I am incredulous that founding fathers can incorporate into America’s founding documents such words as they did and still, from 1776 to 1863, so much as contemplate the slavery system as an economic basis for generating their wealth, rather than treat men on the equal basis vaunted so proudly in said documents. But then, a tobacco plantation is as good a place as anywhere for a smokescreen.

The revolutionary year 1776 is looked to as the foundation of the US. Today, that country wallows in a mire of political mudslinging that threatens to erupt into discord, yea, even into revolution once again (they talk incessantly of dictatorship and insurrection), a mire in which one half of the nation launches brickbats at the other. The minority, whose land it was for thousands of years prior to the coming of European and African alike, do not rule in the US, nor do they even get to engage in its political debate, certainly not with any voice that commands widespread audiences.

But, point me to a senator or congressperson of indigenous race, tell me then that the fighting we see between Democrat and Republican is not simply tantamount to that pre-foundation warfare between France and Britain, Holland and Sweden, imperial power against imperial power, squabbling over another man’s land, and I will point you, Gandhi-like, to masters who lay claim to, and profess hegemony over, a land that is theirs by military conquest alone, governed with little heed to the duty owed by dint of, and in humble gratitude for, the colonisers’ mastery—to all the peoples, whoever they be, across the length and breadth of their putative own nation, and, for that matter, our own world.

If pride comes before the fall, the fall will not always be that of a great empire. The empire itself may even prevail; yet the fall that ensues from the pride can just as easily be one from grace and favour.