Seeing is believing, they say. So, what is “not seeing”? Must we see in order to believe? What if I can’t see but someone phones me to tell me what they see? If I can’t see the caller, surely I can’t believe the caller? And what is belief anyway?

This is a woman on the phone. People on the phone smile a lot. But, just who is she talking to?

Belief is something the truth of which comes to you despite your having no hard evidence. It is visceral. It’s instinct, sixth sense, intuition. Although it may stand to reason, you know it but cannot reason it. A hunch. A gut feeling – that’s where it comes from (hence “visceral”) – and it means that the heart is ruling the head. Such as the classic 11:1 vote at the start of the film “12 Angry Men”, which changes to 0:12, without a penalty shoot-out, as Henry Fonda challenges the hardness of the hard evidence they need to consider. How “hard” hard evidence needs to be depends on who needs to hold something to be true. Judges have clear rules on what they are allowed to hold to be true; the rest of us tend to make it up as we go along.

Eleven of the 12 Angry Men (the sleeve of the 12th’s shirt is just visible, bottom right). This must be the point when the bailiff walks in brandishing a knife.

Some people believe the world is round because that’s how it looks in photos Meteosat says it took from space; some believe things along the lines of “if it looks like whatever, smells like whatever and tastes like whatever, it is whatever”, though disappointment awaits him who reads the ingredients of much of what we eat; and do odourless toxins smell like toxins, therefore? I, for one, happen to quite like almonds.

Earth, which, Meteosat says, is round. But what does it taste like?

We create around us, therefore, a repository of trust. Callers who say they’re someone you know, with the voice you know, from the number you know are probably someone you know. Dave from Microsoft probably isn’t. Unless you work for Microsoft and know someone there called Dave.

Things we believe are things we believe because something other than reasoning supplements or replaces our reasoning. What we reason is not therefore what we believe. It’s what we are persuaded to hold as true. Seeing is holding to be true; believing needs no seeing.

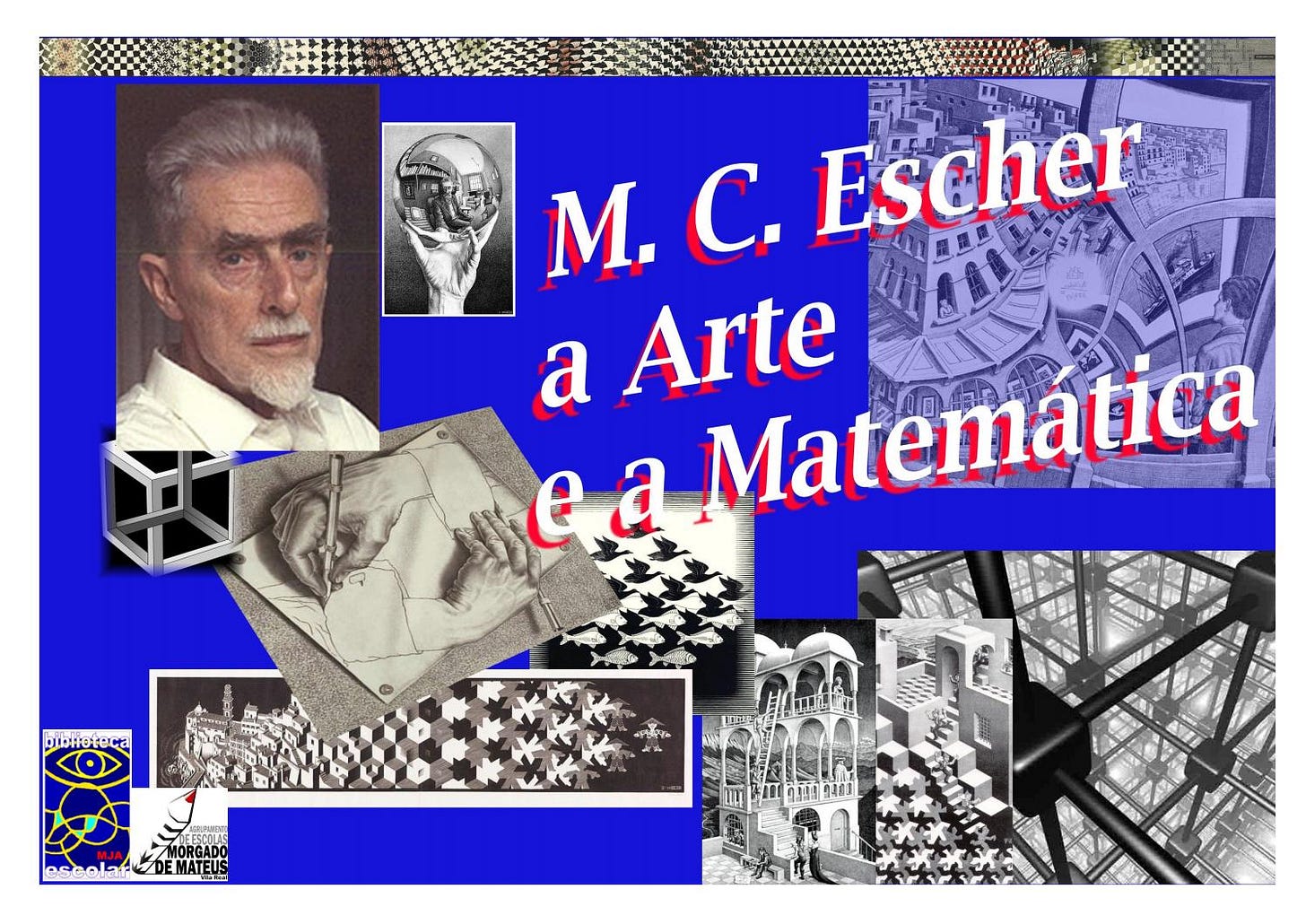

Hearts ruling heads is what we learned not to do in the Enlightenment: out went tittle-tattle and suspicion, in came hard evidence. Actual physical objects. Actual observation of apples falling from trees, pendulums swinging in cathedrals and kettles boiling on stoves. “Watt?” I hear you ask. Yes, him. Here’s some hard evidence: Dutch artist M. C. Escher and some of his artworks. In the second one on the left at the top, Escher is holding one of his balls.

Was M. C. Escher’s world real? What if that which resided inside of him was actually outside of him? What if his top was in his bottom; what, then, if he blew it?

Would it be better if Mr Escher had held an item of somewhat less distorting characteristics? In a way, it depends on what you want to see. And on what Mr Escher wanted the observer to see. And what those are, I cannot know; after all, I don’t have a crystal ball. And if I did say what they were, you might agree or disagree, but you’d never know if I was right; and I would never know if I was right. Instead, we would convene on what is right. That might settle any argument between us, or establish disagreement between us. But it would be a convention only between you and me. Not absolute, and not of application to the world generally. Pinning down what is right (over and above what we believe and what we hold to be true) has been the bane of the legal system since Cato walked this Earth. It has given birth to institutions such as the notarial instrument, witness testimony, the very notion of justice, the mis-trial ruling and, occasionally, the odd accidental execution.

Cato the Elder. The world’s first lawyer. Even then, he was old. When he was younger than this, he wrote the oldest extant bit of Latin. So, third-formers, it’s Cato you have to thank for your travails in life.

The trouble is, we can’t ever know whether what we believe – in the sense of feeling what is true – is true, or in fact false. If what we believe is based on what we’ve been told (e.g. “I love you”), we will hold it to be true until such time as hard evidence persuades us otherwise (like the call record from their mobile phone). At least things on which we have hard evidence can be held to be true, well, for ever, no? Yes. And no. A woman who administers herbal remedies to cure ills is known today as a natural healer. She probably will have encyclopaedias attesting to the power of her herbs. In the Middle Ages, she would have been burned at the stake. Not because people believed innately that she was a witch. But because in the Middle Ages the power of her herbs to cure ills would be taken as hard evidence of the fact she was a witch (and there simply were no encyclopaedias to cite as evidence at trial). The man who fell off a ship in the Americas last week and was located and rescued from the sea 18 hours later may, possibly, ascribe his survival to divine intervention and now hold his survival as hard evidence of the existence of God.

Man overboard. He was rescued 15 hours later, or 18 hours later or 21 hours later, depending on who you read.

But the many people who were not with him bobbing around in the Gulf of Mexico that night may yet be sceptical. About the existence of God. About the existence of the man. About the existence of the ship. For none of those people will have ever seen any one of the three: ship, man, God. What’s more, they may deny the existence of other things that they have not seen; even of things they have seen. The Holocaust. Man walking on the moon. An aircraft nearly landing on the Pentagon. We are as judges in our own cause; but we are free, unlike judges in someone else’s cause, to indeed make it up as we go along. And, into the bargain, we argue with others that our making it up as we go along is superior in worth to their making it up as they go along. It is at this point that living as a hermit starts to assume a certain allure.

The attack on the WTC, New York in 2001, the same day as the Pentagon was, or was not, or might have been, or nearly missed being or wasn’t anywhere near being, hit by an aircraft. Some say it wasn’t terrorist-inspired. I suspect aliens myself.

Seeing is believing all depends on knowing what it is one is seeing. If the default position is that we cannot believe anything unless we have seen it first, we must at least be clear on what we in fact see. We know what we don’t see: things beyond the light spectrum to which our eyes are sensitive. Things behind brick walls. Things in the past and in the future. Things from which we accept that we are separated by the physicality of our world. And that physicality of separation differs for each of us.

Anyone can see anything if they know where to look. It's just, they're not prepared to alter their focal length. A photo is a two-dimensional representation of an object that often has three dimensions. While the first two dimensions, height and breadth, are easier to estimate, the third, depth, is more challenging. Baroque artists played with this by creating the style we call trompe l'oeil – here’s a cute example, from Miami, where it’s not just the cityscapes that can turn out to be fake.

Miami’s Fountainebleau Hotel as it may or may not have looked before it didn’t look like this any more. 1985-2002. You can tell it’s not real. The sea would’ve flooded the town, obviously. And the two flanking key stones are upside down. Amateurs.

In film and on the stage, actors also represent characters, sometimes with two dimensions, sometimes with three.

(Above) Monty Python’s John Cleese and Graham Chapman prepare to execute the fish-slapping dance, whose humour resided in remaining two-dimensional as characters: they portrayed, not acting. Note: Chapman plays the ubiquitous ‘dubious woman’; Cleese plays a woman on the phone (smiling, of course). (Below) Laurence Olivier as Henry V. His character here is three-dimensional, which one can see from the sword with which he is attempting to peremptorily execute one of his own men (the Duke of Cambridge, I reckon). Funny thing is, it looks almost like a painting - now that’s clever. It’s the image of Henry V that schoolboys grew up with when I was a schoolboy. But, made in 1944, the character Olivier played was in fact not Henry V but Winston Churchill.

The jump from playing two dimensions – portrayal – to portraying the third in addition – acting – is the difference between kicking a football down the street and winning the World Cup. Football is a game played by two teams of 11 angry men, who often start life as 11 angry young men. Many of the world’s greatest footballers started their careers by kicking a ball along a street. With time, these players learned about the third dimension, depth. They learned that it was there, what it was and, most importantly, how to play to it and even control it. It’s a skill that seems so self-evident, and yet that is frequently lacking. In footballers. In actors. In architects. In many, who don't know that it is there, what it is and, most importantly, how to play to it or even control it.

Let me leave you with this thought. There are two ways to keep a secret. The first is to lock it up and place an armed guard on it. This has the irksome disadvantage that all the world will know you have a secret and where it is. But the armed guard will prevent anyone from getting in and finding out what it is. Or, you can tell everyone in the world your secret. Everyone. But you encode it so that, to know what the secret is, they first have to have the key. They must insert the key into the lock. That’s the depth. And that’s what unlocks the secret. Omitting the depth leaves us laughing at Monty Python, and dismissing Henry V as “too complicated”. One without any depth; the other with a fathom or two too much.

Because depth is something that we first need to believe in. You do see, don’t you?

Cristian Alvarez, who plays football somewhere in South America, presenting the hard body of evidence.