“The opening theme is intended to be simple and, in intention, noble and elevating ... the sort of ideal call – in the sense of persuasion, not coercion or command – and something above everyday and sordid things.”

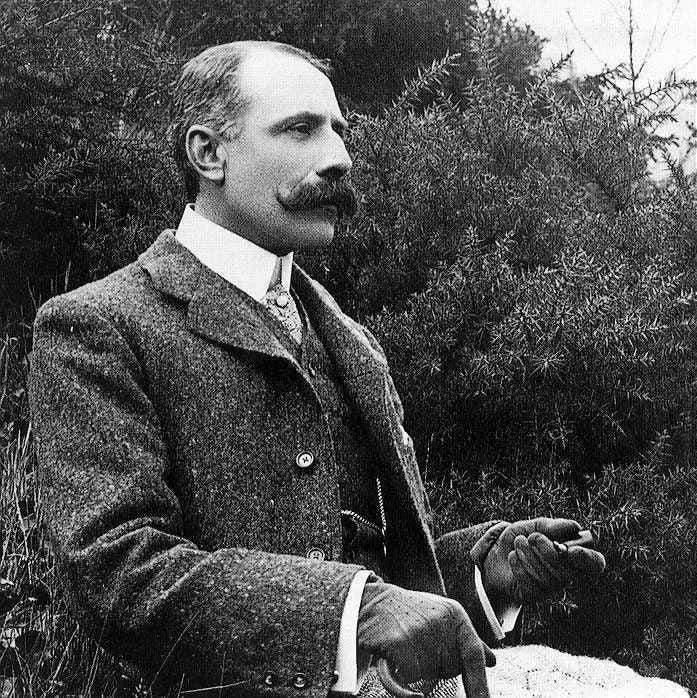

Image: Sir Edward Elgar, 123 years ago (By Unknown author - http://www.geocities.com/hansenk69/elgar3.jpg (broken link), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=126126)

After toying for ten years with writing a musical piece that honoured General Charles Gordon and his last stand at Khartoum, Edward Elgar — of Malvern (no, not the bottler of spring water, the composer) — ultimately cast off the idea of imperial glory — despite the four of his, ultimately, five bombastic “Pomp and Circumstance Marches” of 1901-07 — and devoted his energies to reworking the preparations of his youth for what would be his first symphony: as a non-programmatic work.

Elgar’s first was published by him when he was 61; odd to think that Tchaikovsky wrote his last symphony when he was 53; Elgar has since embedded himself in the British psyche as archetypically English (stiff upper lip and jolly old banter to boot), much aided by the wags of lampoon at Monty Python’s Flying Circus, whose rendering of Philip Sousa’s Liberty Bell march — together with the final raspberry — had already been subjected to their irreverent playfulness.

A symphony declared by its composer to be non-programmatic shouldn’t be scoured for programmatic emblems. They’re easy enough to detect in Richard Strauss’s Alpine Symphony, and in The Hall of the Mountain King from another Edward, Grieg. Even Handel’s Water Music is resplendent in its imagery, even without the water or the fireworks.

With every due respect, I see much imagery in the first symphony from Elgar, one of only two he wrote in their entirety (his third was completed posthumously). And no movement has more imagery than the fourth, and last, of the first. The imagery I conjure in my mind is not of This England, however. It’s far more of Yonder Ukraine. Ukraine is a country that most Britons could not have pointed to on a map a year and a half ago. Now, Britons, all Europeans, and people across the globe pore over maps of Ukraine, although fewer and fewer as each day goes by; as The Guardian’s counter edges upwards from What we know on day 1 to What we know on day 441 of the invasion. Who’d have thought, on day 1, that we’d ever see day 442?

Some might dismiss the story as no longer newsworthy. They win a bit. The other side win a bit. They kill a few. The other side kill a few. Attrition. Advance without advancement. Ukraine has expressed its thanks to Britain for its support. I won’t say it’s never wavered, but it hasn’t yet failed. I say that not because I’m British. But because Edward Elgar was.

Listen, if you care (but only if you care), to that final movement of Elgar’s First. In the link, you can join the last movement at 41.00 minutes, but listen to it all, if you can. It’s in A flat major, a rare symphonic key, and one that evokes deep emotion.

You’ll hear the dark, lugubrious start; the staccato bassoons and trombones tip-toeing across the scene; then, flurries of mystifying activity; and then, and then: the noise, the cacophony, building, retreating, building and sliding; sour notes, bursts; a second assault; the second violins seemingly out of step with the rest of the band — “Keep up, girls!” The sections of the orchestra seem to fight each other; brass heralds new inroads into the score, with colleagues failing to keep up on the assault. “Keep up, man!” The overpowering sense is one of inner, if unified struggle. Elgar’s internal one; Ukraine’s external one.

Then, in the repose that follows, there soars a lilting melody of harmony and oneness. The harp draws the heart to heaven. It’s a love song, dedicated to whatever it is that you love. It swells, as tears well, and yearns, for a height, never quite attained: abruptly cut off, before its apogee; with renewed resilience, it struggles, back, shadowed, in doubt, in despondency; but it’s nevertheless a struggle that persists, before finally, at 47’15”, the band prepares, quietly, for the last. Assault. A march and a wandering brass section announce the final, full-blown offensive; and it comes, in the final theme, at 50 minutes, cyclically retrieved, from the opening portion of the closing movement.

In it, one feels the orchestra almost stumble forward as it achieves cadence yet collects itself for the next advance, not seemingly all together; alternating rallentandos abound. At last, finally, all unite. Before the final allegro section: an alarum is sounded! The wails of the violins are heard, pleading for the triumph; the pace, picks up, and the piece, at last, penetrates, to victory. Victory, so valued, at such a price. It is no glorious wall of sound that greets these victors: resolution is proclaimed, valiantly, if lonesomely, by a single instrument — the trumpets. The end, which sounds after the brass exultation, is ominous: the single note of a tympanum, lifted from its drum-skin like the muffled reverberation of a missile, as it strikes, its last target.

In this symphony, I hear those stiff upper lips, whether they cry “Keep up, man!” or “Наздоганяй, чоловіче!”; I hear the banter of Noël Coward and of Vasyl Baidak. I don’t hear here Russian banter or comedy, no, no. (I cannot honestly name a single Russian banterist or comedian, not without heaping on the irony.) Ukrainians paid Britain a great compliment by calling it their friend. They’d be paying me an even greater one, if they called Elgar their friend, too. As an ideal call — in the sense of persuasion, not coercion or command — and something above everyday and sordid things.

It’s a description I’ve not heard as yet of the Russian incursion into Ukraine. I’ve heard outrage, horror, despondency, anger, revenge, hatred, I’ve heard them all. But there’s something uniquely British, and uniquely Ukrainian, too, in the phrase Elgar chooses. On whatever day of the invasion that final tympanum-missile strikes in reality, it will not be a day too soon. Then, only then, will Ukraine be done with those sordid things.