Striking boys

The elusive objectivity of doing what's right

This article can be heard as a podcast by clicking above.

I think I will have been in fourth, or possibly fifth, form when the boys struck.

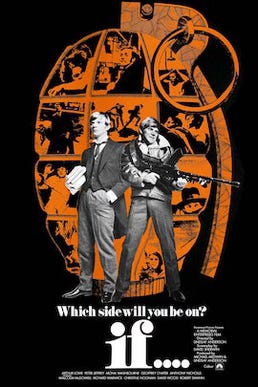

Image: the poster for the 1968 film if … (fair use). In the film, they teach schoolboys to be officers and gentlemen. And are surprised when the boys shoot back.

Mine was a boys’ school. Fee-paying (except for me, who was a clever-clogs with two scholarships; since I couldn’t have two adolescences, I needed to forgo one of the scholarships, so I forwent that one that didn’t come with a bus pass. By the time I was 14, bus conductresses were guffawing derisorily when I presented my bus pass, so advanced was my corporeal maturity. It was their denial of my state of adolescence and the denial of a second simultaneous adolescence by the schools’ governors that persuaded me ultimately to engage in at least three further adolescences, and I’m about to enter my fourth.)

Armed with my bus pass, clearly, I was a non-resident of this school. About half the pupils were resident, however, and occupied the notional houses of Finlay, Vinter and Southerns. I, for my sins, was in Towlson House, a dayboys’ house, the other two of which were Stephenson and Atkinson. All this meant was that, at 5 pm every Monday, Tuesday, Thursday and Friday, and 12 noon on a Wednesday and Saturday, 50% of the school population headed out into the conurbation of Leeds and Bradford to return to the cradle of home-cooked meals and an hour of prep before some telly and bed. For the other 50%, a strict regime of games—tea—first prep—clubs and societies—second prep—dorm, and lights out, was more the order of the evening, and, on the day in question, it was the second of these activities that had caused a storm in the dining hall.

A young gentleman in my own class, who shall go unnamed (unless he reads this and preens himself such as to want to be named) had still been feeling the pangs of pubescent hunger and had approached the head of the kitchen requesting—probably not in the most eloquent of manners—a supplement to his supply of doughy, sliced, white bread. The cook opined that the gentleman in question had had quite enough, and he thereupon replied with a plaintive and sharply barked out riposte, whose terms are embedded in my memory, but which I regret I shall have to reproduce in coded form, as follows:

“Well, that’s a bit b****y, f*****g s**t, innit?”

(He was otherwise so angelically well-spoken, it’s clear the situation had gotten the chap’s back up somewhat.)

The punctuation is my own, added according to the rules of grammar, though I confess the sentence itself was later reported to me, rather than my assessing its intonation from having heard it first hand. The cook in question did, on the other hand, hear it extremely first hand, and I suspect may well have dropped her ladle at the hearing of it.

The matter was reported to the master-in-charge and a reprimand was forthcoming, whereupon battle lines were drawn up: the boy was hungry, and wanted another slice of bread. If his argument wasn’t presented with due de rigueur politesse, was it not nonetheless a warranted request?

The defence artillery, armed with carving forks and looks that could kill more effectively even than carving forks, drew up its own lines: “No, it most certainly was not.”

And that is when the boys struck.

A food strike. The word was put out personally by visits to each form room the next morning by the head boy: all boys were required to attend at lunch, according to the rules of the school; but no boy was required to take lunch during the lunch period and those who chose to join the strike would not be punished for declining their repast. Likewise, those who wished to partake of lunch could do so without recrimination. There would be no recriminations from staff or boys alike against those who took either side of the argument. It was to be a free, democratic choice.

It was the 1970s, and we had lived through power cuts owing to strikes by miners that had seen ugly scuffles at pit heads. But this was an educational establishment, and we were boys learning leadership, obedience and, above all, responsibility. Each of us was faced with a choice that had no consequences outside the walls of our establishment and yet had the most far-reaching of consequences within the walls of our establishment, and within our souls. For the first time in my life, I had to make a decision based on a matter in which I had no direct interest but in which I had the opportunity to demonstrate solidarity with those of my fellows who had every interest in the matter.

How I decided is of no consequence. The strike continued at teatime and the boys’ resolve was clear; the strike was eventually victorious: a full capitulation. The boy who had started it all with his crass defiance had won the day: there would be no rationing of meal supplements like tea, bread and jam for any boy. Sister Maria was undoubtedly over the hills with joy.

That gentleman may well have revelled in his victory, I don’t know. My own feeling as to how I had acted was that I had acted in a manner that was right and honourable. I had not acted in a manner that was calculated to benefit me. I hold to this, even these 50 years on. I will not profess sainthood, I will not assert that I have never acted solely in my own selfish interests and my human mind is such as to banish my guilty memories of having done so, if do so I did (which only leaves me, instead, asserting my imperfection more out of caution than anything else).

In a review of a book about free speech, I read the following: “[though] ‘free speech’ [is] a meaningless catchphrase, it nonetheless remain[s] a supremely powerful rhetorical weapon. Although speech could never really be free … one should always claim to stand for it – if not, your political opponents will inevitably grab the rhetorical high ground and say ‘we’re for free speech and you are for censorship and ideological tyranny.’ At which point whatever serious, worthy argument you’re really trying to make will be almost impossible to salvage.”

It is for this reason that I gloss over where I stand in relation to the 1975 (or 1976) food strike at my school. I wouldn’t like my worthy argument to be almost impossible to salvage. It is said of the authors of the reviewed book’s 22 chapters: Almost all of them reject the classic liberal presumption that society consists of equally autonomous individuals, whose beliefs are made up of abstract notions they rationally assemble—choosing and discarding freely from a universal, neutral marketplace of ideas, in which all propositions are always given a fair and equal hearing.

And, it is upon reading this, that I realise that my non-disclosure of my stance in the 1975 (or 1976) food strike at my school is irrelevant. I can proclaim that my stance was taken on a equitable, democratic basis, that I favoured the party who, I felt, was most deserving, on the balance of all probabilities, of my sympathies, and that I acted without any question of self-interest. And even then, my worthy argument will still be almost impossible to salvage, for there is not an argument in the world that founds in freedom that will ever win the day; for my freedom stands contrary to the freedom of any other and few others’ freedoms are consistent with mine. The shock delivered upon reading the words reject the classic liberal presumption that society consists of equally autonomous individuals is so very palpable simply because the assertion is so true. For, it leads me to a simple conclusion: that any freedom will always be a freedom conferred by majority consent; and that the minority who do not consent will never be free within their own conception of the notion.

The Twitter wars all seem to focus on malicious lies. If we time-travelled back to Winston-Salem’s witch-hunting trials, we’d be able to identify in seconds which were truths and which were malicious lies. Wouldn’t we? How does anyone know what a truth or a lie is and how does anyone know that another acts in malice? “I have no window to look into the conscience of another man” (Sir Thomas More). Yet, we do, of course. We have all these windows. We all see everyone else’s consciences. If only we took care to see our own.

George Orwell said, “If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear.” I think that has be right. But if those who don’t want to hear say things the first camp don’t want to hear, where does the shouting match stop? Where does the considered debate recommence? And where does the shooting start?

I remember this food-strike…….absolutely true

Difficult to believe you may say

I also remember a vegetarian’s anguish at regularly being presented with a fried egg for lunch

He just said to me “ I just wish they could be more imaginative”

Sausage casserole is also a memory I’d like to forget…….