Een NL-versie van deze tekst is hier verder beneden te lezen.

Readers who have been with me on this journey for some time may have seen the following sentiments before, but in a different form. The change of form is due to a change in the question that has been put to me, on this occasion from Top Shelf Theology. If a refreshed approach to God, spirituality, theology and “what’s it all about?” enthuses you, then I can recommend my fellow enquirer over at Top Shelf Theology. Even if you’re not religious, Top Shelf Theology will set your brain whirring. Like the New Yorker crossword.

When I worked in the early 2000s at PricewaterhouseCoopers, part of my work involved pre-publication proofreading and editing of some of the books the firm issued as part of its thought leadership initiatives. One of these was named Substance and the word itself may be hard to grasp if you’re from a sector outside the world of international taxation.

Substance is all about the idea that a transaction or operation that produces some kind of fiscal effect (like the ability to deduct an outlay as allowable expenditure, or routing a transaction through a certain entity or tax jurisdiction, such as to favourably alter the nature of the funds or assets in question) must be shown to also actually change something for the parties: substance is not tangibility, because intellectual property is intangible, but its transfer can have huge effects in terms of substance: imagine buying the rights to the trademark Coca-Cola®: no tangibility; plenty of substance. Substance is the argument by which a tax authority can challenge the form of a transaction that, in fact, changes nothing for the parties in substance.

For religious devotees who are members of an organised church or religion, the form in which they worship confers cultural identity on their act of worship. It gives them a sense of connection, of association, with the other worshippers, as well as with the place where they are worshipping. I once had a partner who is Roman Catholic and I accompanied him to many Catholic places of worship: in Belgium, in Germany, in France and on the island of Malta. There are certain aspects of Catholic churches in all of those places (to which I can add Ireland, Italy, Vatican, Scotland, Canada, the United States, as well as Anglican churches in England and so forth) that are recognisable to any Catholic. The monstrance, the stations of the cross, the saints—Peter with his keys, Anthony bearing the child Christ, James and his shells, Mary dressed in red, Mary dressed in blue, Andrew’s fish and saltire cross, and so on. The progression from porch, to pre-font, to font, to the body of the church, to the rood, the choir, the apse, the east window. The aspergillum, the rosary, the hosts, the creed, the communion.

I shall venture no false knowledge of all that these things betoken; nor shall I pretend any knowledge of the rites, rituals and liturgies of Islam or of Judaism or of Buddhism or of Haitian voo-doo. The meaning of Yom Kippur, Hanukkah or Passover, Ramadan and its ram, the crescent moon and Mecca, the hajj, nor of the associated meals and drink, and the absence thereof; dolls, incense, gongs, minarets and menorahs; Christmas trees and Christmas candles, Christmas presents and Christmases past; Christ the Saviour, bringing Mohammed to the mountain, and bringing home the Francis Bacon.

All that said, there is a distinct difference in look and feel between a church in Malta and one in Ireland. Between a Roman basilica and a Greek orthodox cathedral; between a Free Church of Scotland meeting and a Quaker meeting. Yet, even when Muslims gather to worship, their eyes are directed at the same substantive entity as the Christian or the Jew or any other adherent to a deific religion: the one God, however they call it.

The mystic seeks but one thing in life, and that is union with God. I have lived with a mystic and it can pose its challenges. The fixed goal of union can shatter those who enter into union with such persons, unaware of their mystic aura. But mystics are the greatest proponents of the mantra substance over form. For them, organised religion can become tedious. It’s a poor example, but it would be a little like an Oxford graduate patiently sitting through a geography class with 10-year-olds. Doable, but with forbearance.

However, for those who see religion as an encapsulation, as being part and parcel of their entire cultural persona, in terms of social, national, linguistic, political as well as ideological identity, the form of God is very important. Jesus is white-skinned to northern Europeans; when they view the dark, olive tones of the crucifix in Lucca cathedral, it doesn’t match the images in our childhood bibles. There follows either an epiphany, or a rejection.

God has no form. He has only substance. The mystery and wonder of trans-substantiation makes this clear. Catholics believe less in the molecular change of bread into flesh, of wine into blood at communion; and more in the mystical notion of a oneness with God when the host and the wine are consumed in the act. When I talked recently to a Catholic friend about this, she offered a closer understanding of what trans-substantiation is. And I realised that I believed in it as well, as a raised Protestant, and yet had never identified with the word trans-substantiation.

In point of fact, I never needed to associate with that word: the fact of associating with the sentiments expressed by this lady shows me that we shared an understanding of the substance, even if we’d attributed different forms to the experience. What neither of us ever did, for which I’m grateful, is identify the word trans-substantiation as a mark of division between us. Because it wasn’t. Substance is vastly more important to God than form.

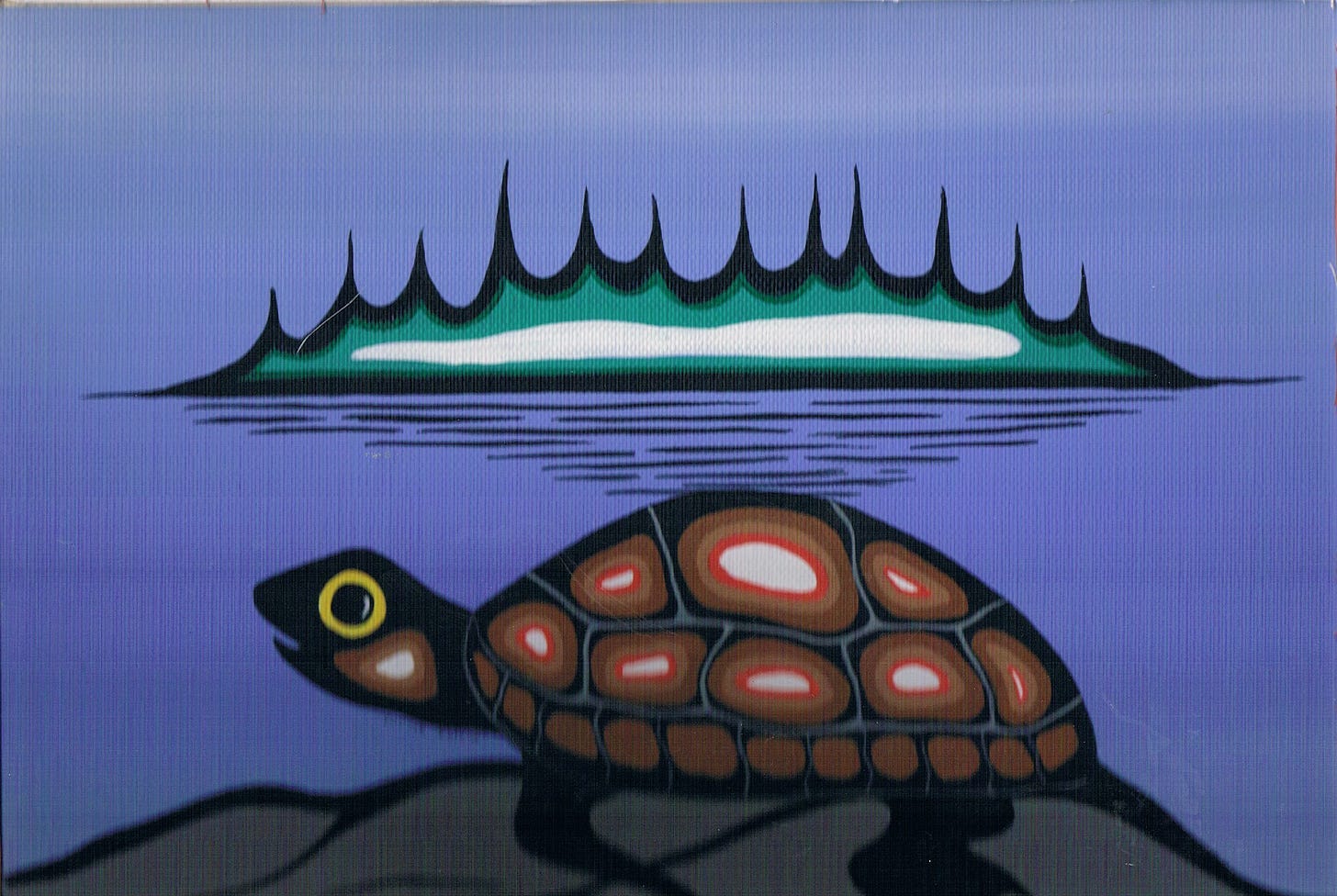

This is a painting that was done for me by a First Nation friend, Shawn Schibler, from Winnipeg in Canada.

Do you recognise the scene? If you are of the Ojibway tribes, you will, instantly. But, if you do not know First Nation traditions, you may need a hint. Here it is: Noah.

The painting depicts the Great Flood. Waynaboozhoo is a spirit of First Nation tradition, not vastly unlike the first world’s Holy Spirit. When the flood came, which we know of with Noah and his building of the Ark, Waynaboozhoo sought refuge on a log that floated in the floodwaters. Many creatures came and joined him on the log, but it was not large enough for them all. Those who could swim would swim next to the log and swap places with other creatures who had rested enough to re-enter the water. The same went for birds: some rested on the log, whilst others flew along with them high above.

One after the other, the creatures tried to reach the bottom of the water, to dredge up earth and use it to reconstruct the land above the water. Many tried, but failed. Finally, the muskrat wanted to try, and was mocked, since he was so small and weak. But he dived to the bottom and had just enough strength to gather some earth and come back to the surface. When he surfaced, he was so tired, he expired and died. The others found the earth in his paw and the turtle asked that the earth be placed on his back, so that a new earth could come from this flood:

“Use my back to bear the weight of this piece of earth. With the help of the Creator, we can make a new Earth.”

Waynaboozhoo put the piece of Earth on the turtle’s back. All of a sudden, the noo-di-noon’ (or winds) began to blow. The wind blew from each of the Four Directions. The tiny piece of Earth on the turtle’s back began to grow. Larger and larger it became, until it formed a mi-ni-si’ (or island) in the water. Still the Earth grew but still the turtle bore its weight on his back.

Waynaboozhoo began to sing a song. All the animals began to dance in a circle on the growing island. As he sang, they danced in an ever-widening circle. Finally, the winds ceased to blow and the waters became still. A huge island sat in the middle of the great water.

From The Mishomis Book (The Book of the Grandfathers) by Edward Benton-Banai

This folk tale tells of mutual aid and mutual respect; of sacrifice that others might live and the wonder of Creation. But it mentions no character called Noah, and no ark, no gopher wood, no animals going in two by two. The form is very different to the biblical flood story. But the substance is all there. It is not an adaptation of the biblical story. It is a tradition dating back over thousands of years of oral First Nation storytelling. It is paralleled with great flood traditions in other cultures as well. It is part of the proof of the veracity in the substance of the great flood story of the Bible. But its form is adapted to local conditions, local creatures and local points of contact, so that the story is redolent for the peoples who shared it.

The great conundrum of the Book of Revelation is that the world’s end will come only when all believe in Him. So, the Christians, for instance, want to make sure everyone believes in the Christian God. Maybe Muslims want us all to believe in the Muslim God. And Jews in the Jewish God, and so on, and so forth. Some of them tell each other, “There is only one God, so therefore you lot are wrong.”

But that isn’t so. Yes, there is only one God; that much is true. But that doesn’t prove others wrong. On the contrary, it proves them right. Because His substance is in each case the same, even if the form is different. His substance is love.

Recently, I spoke to someone I know who is Dutch. In an allusion to the recent general election in the Netherlands, I quipped, “Your country will soon be getting a new prime minister.” He replied, “Yes, well, we shall have to see.”

That was nonsense, for a start: Mr Rutte had retired, so whoever was elected, there would be a new prime minister. Then, the very next thing that he said shook me to the core: “Do you know, forty per cent of the people in Amsterdam are Muslim?” Before I could respond, he’d reinforced his statement: “Forty per cent!”

I bit my tongue and simply said, “My!”

In October, I was in the Netherlands and my travels took me to the home of a friend of mine and her husband, who live in a small town not far from Arnhem. The husband is of the Dutch Reformed faith. My friend is Roman Catholic. I was positively shocked when she related to me that their town is so entrenched in the Reformed bible belt, she cannot reveal to her neighbours that she is of the Roman Catholic faith. She and her husband know that she would be shunned by all.

I don’t know what percentage of her town is Roman Catholic, but she feels that, if she herself isn’t, her religious beliefs are certainly unwelcome there. And the 40 per cent of Muslims—if that figure’s correct—who live in Amsterdam are unwelcome there in the eyes of a man who lives … in Belgium. Three hours away from the Dutch capital.

Perhaps the Dutch have a different god to the rest of humanity. Perhaps they just think so. I, for one, do not think so.

God isn’t for everyone. He’s for every one. What I mean with this is that God cannot be presented in a uniform manner that will be identified with and worshipped and culturally assimilated by all the peoples of the world. His form will change according to how those in different parts of the world have envisioned Him in their thoughts and dreams, and how He has revealed Himself to them in terms that they could understand. In that sense, the form in which God makes Himself apparent will not be for everyone. But the substance in which He reveals himself to each individual will be the same. That substance is love—for every one of us. And the form it takes will be that with which we ourselves most closely associate, because God loves each one of us as His individual children, and not as a body politic, amassed under a single flag, denoted by borders drawn on maps, extolled in one particular language, by folk of one particular skin colour. All these are trappings of man, which he deploys to his own material ends in sequestering the Earth to his own selfish wants. God knows no flag, no borders, no skin colour, no race, no national anthem, no language. He knows only love. For each and every one of us; but not for everyone, because everyone is just like the smokescreens of democracy and equality: terms bastardised by man and re-forged into them and us.

The Belgian Criminal Prosecutions Code of 1808 makes repeated reference to the term: de waarheid aan de dag brengen—to bring to light the truth.

There is an incidental jurisprudential argument that the truth is not what a court seeks (and I don’t mean that in the sense of the Nicholson/Cruise confrontation in A Few Good Men). Justice is cognisant of the difficulty in establishing truth, so it satisfies itself with bringing to light enough truth. Nonetheless, the Code vaunts this aspiration: to bring the truth to light.

And, that being so, one might be tempted to inscribe the mantra “the aim of justice is to bring to light the truth” over the portals of every court of law in the land. If one did so, then one could just as easily inscribe over the portals of every place of worship in the land “the aim of worship is to bring to light the truth.”

An irony resides in the fact that the method pursued in the court of law for establishing the truth entails excluding anything for which no corroborated evidence can be adduced; the method pursued in the place of worship, on the other hand, entails pursuing paths of enquiry that entail faith, and for which no corroborated evidence can be adduced that would be acceptable to a court of law.

Take a horse race. The winner is the first mounted horse to pass the finishing post. But, if the first are to be last and the last first, who wins horse races in Heaven? Part of the secret to finding God is precisely to look for Him in those places where we would least expect to find Him, and to eschew the legal methods by which we expect that He can be proved; since, by those methods, He simply cannot be proved. In part, because no court of law will admit as evidence the evidence by which God proves Himself to me. And because justice won’t admit my faith as evidence, sceptics likewise reject God, for want of proof.

That is our mortal limitation, and we often cannot recognise it as such. We talk of scant evidence as if we were standing in a court of law. We demand evidence of the unprovable and, when a witness does eventually take the stand to provide evidence of the truth, justice seeks to ensure truth by shoving into their hand the very Holy Bible whose God their evidence is supposed to prove; upon which they are to swear before God that the evidence they will give shall be … the truth.

Further reading, if you care:

Anarchy in the UK-raine: pondering black lines

First published 27 June 2022 Thanks for reading The Endless Chain! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work. The others. That’s all of us. The Welsh. The Walloons. The Gauls. The others. Etymology is a strange area of study. It tells us where a word comes from, how it arose, how it was transformed during the history of its existence and …

[NEDERLANDSE VERSIE:]

Substance over form

Een verfriste benadering van theologie

Lezers die al enige tijd met mij op deze reis zijn, hebben misschien de volgende gevoelens eerder gezien, maar in een andere vorm. De verandering van vorm is het gevolg van een verandering in de vraag die mij is gesteld, bij deze gelegenheid vanuit Top Shelf Theology. Indien een verfriste benadering van God, spiritualiteit, theologie en “waar gaat het allemaal over?” je enthousiast maakt, dan kan ik mijn collega-onderzoeker bij Top Shelf Theology aanbevelen. Zelfs als je niet religieus bent, zal Top Shelf Theology je hersenen laten suizen. Net zoals het kruiswoordraadsel van The New Yorker.

Toen ik in het begin van de jaren 2000 bij PricewaterhouseCoopers werkte, bestond een deel van mijn werk uit het pre-publicatie proeflezen en bewerken van enkele van de boeken die het bedrijf heeft uitgegeven als onderdeel van zijn thought leadership-initiatieven. Een daarvan heette Substance en het woord zelf is misschien moeilijk te begrijpen als je uit een sector buiten de wereld van internationale belastingen komt.

Substantie gaat over het idee dat een transactie of operatie die een of ander fiscaal effect heeft (zoals de mogelijkheid om kosten af te trekken als toelaatbare uitgave, of het routeren van een transactie via een bepaalde entiteit of fiscaal rechtsgebied, met het gunstig veranderen van de aard van de gelden of activa in kwestie) moet worden aangetoond om ook daadwerkelijk iets voor de partijen te veranderen: substantie is niet tastbaarheid, omdat intellectueel eigendom immaterieel is, maar de overdracht ervan kan inhoudelijk enorme effecten hebben: stel je voor dat je de rechten op het handelsmerk Coca-Cola® koopt: geen tastbaarheid; veel substantie. Substantie is het argument waarmee een belastingdienst de vorm van een transactie kan aanvechten die voor partijen feitelijk niets inhoudelijk verandert.

Voor religieuze toegewijden die lid zijn van een georganiseerde kerk of religie, verleent de vorm waarin zij aanbidden een culturele identiteit aan hun daad van aanbidding. Het geeft hen een gevoel van verbondenheid, van associatie, met de andere aanbidders, evenals met de plaats waar ze aanbidden. Ik had ooit een partner die rooms-katholiek is en ik vergezelde hem naar vele katholieke gebedshuizen: in België, in Duitsland, in Frankrijk en op het eiland Malta. Er zijn bepaalde aspecten van katholieke kerken op al die plaatsen (waaraan ik Ierland, Italië, Vaticaanstad, Schotland, Canada, de Verenigde Staten, evenals Anglicaanse kerken in Engeland enzovoort kan toevoegen) die herkenbaar zijn voor elke katholiek. De monstrans, de staties van het kruis, de heiligen—Petrus met zijn sleutels, Antonius die het kind Christus draagt, Jakobus en zijn schelpen, Maria in het rood gekleed, Maria in het blauw gekleed, Andreas’ vis en zoutkruis, enzovoort. De progressie van portiek, naar vestibule, naar doopvont, naar het lichaam van de kerk, naar het kruisbeeld, het koor, de apsis, het oostraam. Het aspergillum, de rozenkrans, de hosties, de geloofsbelijdenis, de communie.

Ik zal me geen valse kennis van al deze dingen wagen; noch zal ik doen alsof ik enige kennis heb van de riten, rituelen en liturgieën van de islam of van het jodendom of van het boeddhisme of van de Haïtiaanse voo-doo. De betekenis van Jom Kippoer, Chanoeka of Pesach, Ramadan en zijn ram, de halve maan en Mekka, de hadj, noch van de bijbehorende maaltijden en drankjes, en de afwezigheid daarvan; poppen, wierook, gongs, minaretten en menora’s; kerstbomen en kerstkaarsen, kerstgeschenken en kerstmissen geschonken; Christus de Verlosser, het brengen van Mohammed naar de berg en het demystificeren van de fabels van Francis Bacon.

Dat gezegd hebbende, er is een duidelijk verschil in look en feel tussen een kerk in Malta en een in Ierland. Tussen een Romeinse basiliek en een Grieks-orthodoxe kathedraal; tussen een Free Church of Scotland vergadering en een Quaker bijeenkomst. Maar zelfs wanneer moslims samenkomen om te aanbidden, zijn hun ogen gericht op dezelfde inhoudelijke entiteit als de christen of de jood of een andere aanhanger van een godvruchtige religie: de ene God, hoe ze het ook noemen.

De mysticus zoekt maar één ding in het leven, en dat is vereniging met God. Ik heb met een mysticus samengewoond en er kunnen er uitdagingen van vloeien. Het vaste doel van vereniging kan degenen verbrijzelen die zich met dergelijke personen verenigen, zijnde zich niet bewust van hun mystieke aura. Maar mystici zijn de grootste voorstanders van de mantra substantie boven vorm. Voor hen kan georganiseerde religie vervelend worden. Het is een slecht voorbeeld, maar het zou een beetje lijken op een afgestudeerde uit Oxford die geduldig door een aardrijkskundeles met 10-jarigen zit. Doebaar, maar met verdraagzaamheid.

Voor degenen die religie echter zien als een inkapseling, als onderdeel van hun hele culturele persona, in termen van sociale, nationale, taalkundige, politieke en ideologische identiteit, is de vorm van God erg belangrijk. Jezus heeft een witte huid voor Noord-Europeanen; als ze de donkere, olijftinten van het kruisbeeld in de kathedraal van Lucca zien, komt het niet overeen met de afbeeldingen in onze kinderbijbels. Er volgt ofwel een openbaring, ofwel een afwijzing.

God heeft geen vorm. Hij heeft alleen inhoud. Het mysterie en wonder van transsubstantiatie maakt dit duidelijk. Katholieken geloven minder in de moleculaire verandering van brood in vlees, van wijn in bloed bij de communie; en meer in de mystieke notie van een eenheid met God wanneer de hostie en de wijn tijdens de ceremonie worden geconsumeerd. Toen ik hier onlangs met een katholieke vriendin over sprak, bood ze een beter begrip van wat transsubstantiatie is. En ik besefte dat ik er ook in geloofde, als opgevoed protestant, en me toch nooit met het woord transsubstantiatie had vereenzelvigd.

In feite hoefde ik me nooit met dat woord te associëren: het feit dat ik me met de gevoelens van deze dame associeerde, laat me zien dat we een begrip van de substantie deelden, zelfs als we verschillende vormen aan de ervaring hadden toegeschreven. Wat geen van ons ooit heeft gedaan, waarvoor ik dankbaar ben, is het woord transsubstantiatie als een teken van verdeeldheid tussen ons te identificeren. Omdat hij het niet was. Substantie is voor God veel belangrijker dan vorm.

Dit is een schilderij dat voor mij is gemaakt door een First Nation-vriend, Shawn Schibler, uit Winnipeg in Canada.

Herken je de scène? Als je tot de Ojibway-stammen behoort, doe je dat meteen. Maar als je de tradities van de First Nation niet kent, dan heb je misschien een hint nodig. Hier is het: Noach.

Het schilderij beeldt de zondvloed uit. Waynaboozhoo is een geest van de First Nation-traditie, niet veel anders dan de Heilige Geest van de eerste wereld. Toen de vloed kwam, die we kennen bij Noach en zijn bouw van de Ark, zocht Waynaboozhoo zijn toevlucht op een boomstam die in het overstromingswater dreef. Veel wezens kwamen en voegden zich bij hem op de stronk, maar het was niet groot genoeg voor hen allemaal. Degenen die konden zwemmen, zwommen naast de boomstam en wisselden van plaats met andere wezens die genoeg rust hadden gehad om opnieuw het water in te gaan. Hetzelfde gold voor vogels: sommigen rustten op de boomstam, terwijl anderen hoog boven hen meevlogen.

De een na de ander probeerden de wezens de bodem van het water te bereiken, aarde op te graven en te gebruiken om het land boven het water te reconstrueren. Velen probeerden het, maar faalden. Uiteindelijk wilde de muskusrat het proberen en werd hij bespot, omdat hij zo klein en zwak was. Maar hij dook naar de bodem en had net genoeg kracht om wat aarde te verzamelen en terug naar de oppervlakte te komen. Toen hij opdook, was hij zo moe, hij sneuvelde en stierf. De anderen vonden de aarde in zijn poot en de schildpad vroeg om de aarde op zijn rug te plaatsen, zodat er een nieuwe aarde kon komen van deze overstroming:

“Gebruik mijn rug om het gewicht van dit stuk aarde te dragen. Met behulp van de Schepper kunnen we een nieuwe aarde maken.”

Waynaboozhoo plaatste het stuk aarde op de rug van de schildpad. Plotseling begonnen de noo-di-noon’ (of winden) te waaien. De wind waaide uit elk van de Vier Richtingen. Het kleine stukje aarde op de rug van de schildpad begon te groeien. Groter en groter werd het, totdat het een mi-ni-si’ (of eiland) in het water vormde. Nog steeds groeide de aarde, maar nog steeds droeg de schildpad haar gewicht op zijn rug.

Waynaboozhoo begon een lied te zingen. Alle dieren begonnen in een cirkel te dansen op het groeiende eiland. Terwijl hij zong, dansten ze in een steeds groter wordende cirkel. Uiteindelijk hield de wind op te waaien en werd het water stil. Een enorm eiland zat midden in het grote water.

Uit The Mishomis Book (het boek van de grootvaders) door Edward Benton-Banai

Dit volksverhaal vertelt van wederzijdse hulp en wederzijds respect; van opoffering zodat anderen kunnen leven en het wonder van de Schepping. Maar het vermeldt geen personage dat Noach heet, en geen ark, geen goferhout, geen dieren die twee aan twee naar binnen gaan. De vorm is heel anders dan het Bijbelse overstromingsverhaal. Maar de substantie is er allemaal. Het is geen aanpassing van het bijbelse verhaal. Het is een traditie die teruggaat tot duizenden jaren van mondelinge First Nation-verhalen. Het loopt ook parallel met grote-overstromingstradities in andere culturen. Het maakt deel uit van het bewijs van de waarachtigheid in de inhoud van het grote-overstromingsverhaal van de Bijbel. Maar de vorm is aangepast aan de lokale omstandigheden, lokale wezens en lokale contactpunten, zodat het verhaal overduidelijk is voor de mensen die het deelden.

Het grote raadsel van het boek Openbaring is dat het einde van de wereld alleen zal komen als iedereen in Hem gelooft. Zo willen de christenen er bijvoorbeeld zeker van zijn dat iedereen in de christelijke God gelooft. Misschien willen moslims dat we allemaal in de moslimgod geloven. En Joden in de Joodse God, enzovoort, enzovoort. Sommigen van hen zeggen tegen elkaar: “Er is maar één God, dus daarom hebben jullie het mis.”

Maar dat is niet zo. Ja, er is maar één God, zoveel is waar. Maar dat bewijst niet dat anderen ongelijk hebben. Integendeel, het bewijst hun gelijk. Omdat Zijn substantie in elk geval hetzelfde is, ook al is de vorm anders. Zijn substantie is liefde.

Onlangs sprak ik met iemand die ik ken en die Nederlander is. In een toespeling op de recente algemene verkiezingen in Nederland grapte ik: “Jullie land krijgt binnenkort een nieuwe premier.” Hij antwoordde: “Ja, nou, we zullen het moeten zien.”

Dat was om te beginnen onzin: de heer Rutte was teruggetrokken, dus wie er ook verkozen werd, er zou een nieuwe premier komen. Toen, het volgende dat hij zei, schokte me tot in de kern: “Weet je dat veertig procent van de mensen in Amsterdam moslim is?” Voordat ik kon reageren, had hij zijn verklaring versterkt: “Veertig procent!”

Ik beet op mijn tong en zei gewoon, “Amai!”

In oktober was ik in Nederland en mijn reizen brachten me naar het huis van een vriendin van mij en haar man, die in een klein stadje niet ver van Arnhem wonen. De man is van het Nederlands Hervormde geloof. Mijn vriend is rooms-katholiek. Ik was volledig geschokt toen ze me vertelde dat hun stad zo diep geworteld is in de Hervormde bijbelgordel, dat ze niet aan haar buren kan onthullen dat ze van het rooms-katholieke geloof is. Zij en haar man weten dat ze door iedereen zou worden gemeden.

Ik weet niet welk percentage van haar stad rooms-katholiek is, maar ze voelt dat, als ze dat zelf niet is, haar religieuze overtuigingen daar zeker niet welkom zijn. En de 40 procent van de moslims—zo dat cijfer zou kloppen—die in Amsterdam woont, is daar niet welkom in de ogen van een man die … in België woont. Drie uur rijden van de Nederlandse hoofdstad.

Misschien hebben de Nederlanders een andere god dan de rest van de mensheid. Misschien denken ze dat gewoon. Ik vind van niet.

God is niet voor iedereen. Hij is voor iedere één. Wat ik hiermee bedoel is dat God niet kan worden gepresenteerd op een uniforme manier die zal worden geïdentificeerd met en aanbeden en cultureel geassimileerd door alle volkeren van de wereld. Zijn vorm zal veranderen in overeenstemming met hoe mensen in verschillende delen van de wereld Hem hebben voorgesteld in hun gedachten en dromen, en hoe Hij Zichzelf aan hen heeft geopenbaard in termen die zij konden begrijpen. In die zin zal de vorm waarin God Zichzelf kenbaar maakt niet voor iedereen zijn. Maar de substantie waarin Hij zich aan elk individu openbaart, zal hetzelfde zijn. Die substantie is liefde—voor ieder van ons. En de vorm die het aanneemt zal die zijn waarmee we onszelf het meest associëren, omdat God van ieder van ons houdt als Zijn individuele kinderen, en niet als een politiek lichaam, vergaard onder een enkele vlag, aangegeven door grenzen getekend op kaarten, geprezen in een bepaalde taal, door mensen van een bepaalde huidskleur. Dit zijn allemaal attributen van de mens, die hij inzet voor zijn eigen materiële doeleinden door de aarde in beslag te nemen voor zijn eigen egoïstische behoeften. God kent geen vlag, geen grenzen, geen huidskleur, geen ras, geen volkslied, geen taal. Hij kent alleen liefde. Voor ieder van ons; maar niet voor iedereen, want iedereen is net als de rookgordijnen van democratie en gelijkheid: termen die door de mens zijn verbasterd en opnieuw in hen en ons zijn gesmeed.

Het Belgische Wetboek van Strafvordering van 1808 verwijst herhaaldelijk naar de term: de waarheid aan de dag brengen.

Er is een incidenteel jurisprudentieel argument dat de waarheid niet is wat een rechtbank zoekt (en dat bedoel ik niet in de zin van de Nicholson/Cruise-confrontatie in A Few Good Men). De Justitie is zich bewust van de moeilijkheid om de waarheid vast te stellen, dus stelt zij zich tevreden met het aan het licht brengen van voldoende waarheid. Desalniettemin prijst het Wetboek deze aspiratie: de waarheid aan het licht brengen.

En, als dat zo is, zou men in de verleiding kunnen komen om de mantra “Het doel van de justitie is om de waarheid aan het licht te brengen” over de portalen van elke rechtbank in het land te schrijven. Als men dat zou doen, dan zou men net zo goed over de portalen van elke plaats van aanbidding in het land kunnen schrijven “Het doel van aanbidding is om de waarheid aan het licht te brengen.”

Een ironie schuilt in het feit dat de methode die in de rechtbank wordt gevolgd voor het vaststellen van de waarheid inhoudt dat alles wordt uitgesloten waarvoor geen bevestigd bewijs kan worden aangevoerd; de methode die in de plaats van aanbidding wordt gevolgd, daarentegen, omvat het nastreven van wegen van onderzoek die geloof met zich meebrengen, en waarvoor geen bevestigd bewijs kan worden aangevoerd dat aanvaardbaar zou zijn voor een rechtbank.

Neem bv. een paardenrace. De winnaar is het eerste bereden paard dat de finish passeert. Maar als de eersten de laatsten en de laatsten de eersten zijn, wie wint er dan paardenraces in de hemel? Een deel van het geheim om God te vinden, is juist om Hem te zoeken op die plaatsen waar we Hem het minst zouden verwachten te vinden, en om de wettelijke methoden te vermijden waarmee we verwachten dat Hij kan worden bewezen; omdat Hij met die methoden eenvoudigweg niet kan worden bewezen. Gedeeltelijk omdat geen enkele rechtbank het bewijs zal toelaten waarmee God Zichzelf aan mij bewijst. En omdat de justitie mijn geloof niet als bewijs wil accepteren, verwerpen sceptici ook God, bij gebrek aan bewijs.

Dat is onze sterfelijke beperking en die kunnen we vaak niet als zodanig herkennen. We praten over schaars bewijs alsof we in een rechtbank staan. We eisen bewijs van het onbewijsbare en wanneer een getuige uiteindelijk het gestoelte ingaat om bewijs van de waarheid te leveren, probeert de justitie de waarheid te waarborgen door de Heilige Bijbel in zijn hand te duwen wiens God zou moeten worden bewezen door zijn getuigenis; waarop ze vóór God moeten zweren dat het bewijs dat ze zullen geven ... de waarheid zal zijn.

Verder lezen, als het je kan schelen: