The Brussels Congress Column and its Freedom Quarter

SOCIETY. THEOLOGY. LAW. A quarter of our God-given freedom

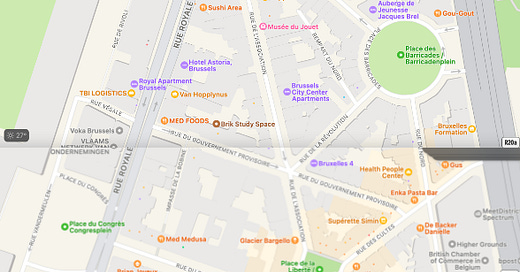

In Brussels, there stands a monument dating from 1859, called the Congress Column. It marks the centre of a part of the city now known as the Freedom Quarter. It contains streets rejoicing in names like:

Rue de la Presse (Press Street),

Rue de la Croix de Fer (Iron Cross Street — the Iron Cross being the medal that rewarded fighters in the Belgian revolution of 1830),

Rue du Parlement (Parliament Street);

Rue des Cultes (Cult Street),

Place des Barricades (Barricades Circus),

Rue de l’Association (Association Street),

Rue de la Révolution (Revolution Street),

Rue du Gouvernement provisoire (Provisional Government Street),

Rue van Orley (named for a family of Flemish painters), and, of course,

Place de la Liberté (Liberty Square).

Image from Apple “Map”.

The area is the centre of freedom in Belgium. The freedom from Dutch hegemony, wrought in 1830. Hence: barricades, the Iron Cross, associations and togetherness, the press, and religious practices (or cults). But, it has to be noted that the area is bounded by some very symbolic institutions and streets. To the south is Belgium’s federal parliament, which enacts the laws that bind these freedoms. To the west is Rue Royale (Royal Street), which celebrates the royalty that is our head of state and our dominant domain. To the north stands the Finance Tower, the headquarters of our inland revenue service; and, next to it, Boulevard Bischoffsheim, which celebrates a family of bankers that ruled many a nation’s roost during its own period of hegemony. At the south-east corner stands the monument to La Brabançonne, our national anthem, and our duty.

The freedoms encapsulated — literally — within the Freedom Quarter are bounded on all sides by rule-makers, finance authorities, banks and national duty. Freedom anywhere must know bounds, but Brussels’ Freedom Quarter really does set the bounds of freedom down in a graphic, a cartographic, manner.

The heart of the Brussels Freedom Quarter is the Congress Column. This symbol of freedom is topped off by a statue of our first king, Leopold I; all our freedom is subject to his majesty’s prerogative, so the column would appear to say.

Following the First World War, an unknown soldier was interred at the foot of the column and there burns there our eternal flame of remembrance. Passers-by, in cars, on foot or on buses and trams, are exhorted by a bold notice to remove their headgear when passing. I have done so on occasion, because I recognise my forebears’ contribution to my own freedoms today. But what, I wonder, is the purpose of the notice? For I have seen many pass the monument by, who never paid the notice the slightest heed.

Perhaps the notice was erected by order of a law, passed by a duly elected parliament. In which case, those who fail to remove their headgear are in contravention of that law. But, if it is by law that they are obliged to do so, why is nobody prosecuted for breach of it? Perhaps they are; I don’t know. But what, if there were such a law, would be the purpose of such a law, if such a law were never to be enforced?

The notion is not so very outlandish. When I first visited Paris in the 1970s, I was curious to see that subway trains reserved certain seating by priority to mutilés de guerre: the war wounded. Quite how one knew by sight that an ex-service person was a mutilé de guerre is questionable but, I’m assured, such entitled persons carried a permit by which they could prove their right to take the seat before others. French law imposed an obligation on travellers that one might consider to be a natural courtesy to be extended to any fellow traveller who has greater mobility issues than oneself.

Then, again, perhaps the notice at the Congress Column was erected by a conscientious council that wished to exhort passers-by to pay respect to our fallen in the First World War, but never intended to impose a penalty on those who failed to comply. What, then, is the purpose of that? An exhortation to pay homage to the fallen?

Surely, those who feel the urge to pay homage will do so; and those who are forced to pay homage will do so under sufferance; and those who don’t pay homage will — what? Be looked down upon by their fellow citizens for not sharing their own sentiments of homage, or for defying a custom they themselves felt obliged to comply with?

Will there one day be a camera fixed to the monument, to check which citizens comply with the exhortation, and which do not? The Paris metro rule was a provision that was enforceable at law, and yet it enforced what the Congress Column respectfully requests: respect for those who have served the nation in wartime. If you failed to show respect in a Paris train, you were theoretically liable to punishment at law; failure at the Congress Column leads only to public social censure, if that, but no penalty. In both cases, France and Belgium fought their wars for freedom. Freedom that is celebrated in the Freedom Quarter of Brussels.

In a freedom quarter, one might have thought that one freedom that should be guaranteed is the freedom to not do something that is not compelled by law; and the freedom to do something that is not prohibited by law. The exhortation at the Congress Column leaves one in doubt as to what one’s freedoms are as regards headgear removal when passing the monument. And that is something that is all too common to freedoms: in just how far are we free?

In the Bible’s Old Testament, God restricted man’s freedom in ten manners. We call them the Ten Commandments. The first four of these concern God Himself (no other God before Him, no graven image, not to take His name in vain, keep the Sabbath). The fifth is a curious one, which I shall return to anon. The sixth to tenth cover what we now know as “natural law”: the prohibitions against killing, adultery, stealing, mendacity and covetousness.

The fifth commandment is that one should honour one’s father and mother and, I believe, it is questionable why it is there at all and, if one accepts simply that it is there, whether it belongs to the set of rules that pertain to God the Father, or whether it forms part of the natural laws, as named.

What is striking about the Ten Commandments is that they make no provision for honouring anyone other than (a) God, (b) one’s father and (c) one’s mother. The other provisions all pertain to not harming one’s fellow man. The mother is a core element of the holy scripture of Muslim believers; fathers play a subsidiary role in the words of the Prophet Mohammed. The Jewish and Christian faiths place much greater emphasis on the two parents in equal measure. But nowhere is one exhorted under the Ten Commandments to honour anyone else. One is simply exhorted not to kill them, make them cuckolds, steal from them, lie about them or covet their possessions. Our God of Love only introduces that concept, and then for all, including Him, when He sends His Son to us, Jesus.

And, more to the point, honour is not love. Those who do raise their headgear when passing the Congress Column cannot truly be said to love the fallen, even if they do honour them. Love, in the romantic sense, is a visceral thing: one might be able to stymie its effects, but the pining of the heart arises despite any efforts by them who feel it to subdue it. Hatred, its contrary sentiment, is not far different.

We can pass laws to subdue the acts of those who bear hatred in their hearts but we cannot actually stop people hating each other; and, likewise, in the Ten Commandments, God stops short of obliging his folk to love one another; instead, He limits Himself to commanding us to at least not breach the five natural laws that serve to protect our fellow man, and at least to honour our parents: His equivalent of a request to raise our headgear to them.

When Jesus comes in the New Testament, even He does not command us to love everyone. God is in: Love thy God the father with all thy heart, with all thy soul, with all thy mind (Matthew 22: 37). And he goes on to command us to love our neighbour (our fellow man) as we love ourselves. So, if we despise ourselves, it is within contemplation that we despise to a like extent those who are our fellow citizens. There is a trite saying that charity begins at home. What that truly means is that love (St Paul took charity in its original sense, meaning love) begins with those who love themselves; so, to be able to love others, we must first love ourselves. And the measure of our love to others will be the measure of our love to ourselves. Hence, if a thug acts aggressively to his fellow man, that can be taken as a sign that he does not love himself (it’s often the case), for, if one’s actions towards others are a reflection of the love that resides at home, then they can be used deductively to determine in how far a thug loves himself. Or can’t they?

Jesus’s love negated all the five natural laws, and it is easy to see why: those who love themselves will love others and that entails not killing them, not stealing from them and so on. And, more to the point, love of others includes one’s parents. Here, not simply honour is exhorted, but visceral love to the extent that you love yourself.

Thugs go to heaven, I think. Because they love others as they love themselves, and thus one might almost consider Jesus’s words as meaning everyone will go to heaven (unless they’re rich, that is, and quite a few thugs aren’t).

I leave for now to one side another strange provision of the Ten Commandments: number one. You shall have no other God before me. Why before me? Does that mean one is free to have other gods, but none who are before me? As I say, left to one side, for further reflection.

We spend a goodly portion of our lives embroiled in rules, even if not embroiled in God’s rules. Some are imposed by law and some are imposed by custom or by doing the right thing. We run expensive court systems to reprimand those who breach laws, and prisons to punish them. We invent laws the whole time: articles of association of companies, staff regulations, holiday rules, contracts, service agreements, do not walk on the grass, drive on the right, remove your hat at the Congress Column. Do not trade with Russia. Report thefts to claim under your insurance. Keep your dog on a leash. Some countries execute their criminals, and some do so for crimes that are not even crimes in other countries. And yet God does not say, “Do not murder,” but rather, “Do not kill.” What we label as legitimate killing is actually killing. Or did I misunderstand what God told us?

Is that really how God wanted us to spend our three score and ten years on His Earth? Encased in our fellow man’s rules? Or, instead, free? Did he intend us to spend our lives long with controlling, supervising, regulating each other and punishing those who contravene our norms, or even His norms? Or did He prefer to have his sheep enjoy the life He had bestowed on them, with the fruits He had given them to live off and simply to forbear from killing, thieving, coveting, being promiscuous and lying?

Ten Commandments, inscribed on stones, are all that we need to understand. If understand we can, that is.