There is a place of which you’ll have surely heard, which is now twice the size of Great Britain and is made up quite simply of plastic. Plastic that was thrown away, whether at sea or 1,000 miles inland, whether wrapped around today’s fancy lunch or tomorrow’s fancy goods. Lunch should, after all, be packed for consumption on the go; and fancy goods ain’t so fancy when they arrive in bits. The place is, we might be relieved to know, in the Pacific Ocean, far from the view of most of us. But there are mountains of plastic much closer to home, even if home is not Polynesia.

Murano is famous for its glass-making, and it was to the isle of Murano—its furnaces kept separate from the all-too-combustible dwellings on Venice’s main islands—that traders would come to purchase its entrancing specialties. Carefully, they would pack them in sawdust and straw, into timber crates, hauled aboard ships for transport to foreign parts, where (once the rats had been dealt with) the precious goods could be unpacked, inspected and wondered at, then sold at handsome profits, such was the yen for Murano glassware

Image: A disintegrating storage box of mine, my own classic, red, Murano glassware, and the bag my breakfast cereal came in.

The same went for silks, wrapped in muslin as protection, or for spices, packed into earthenware pots and sealed with wax for the journey, to maintain their scintillatingly seductive freshness. In time, came the tin, into which all sorts of comestibles were packed, like Oxo cubes and Huntley & Palmers biscuits, before the tin itself became a sealed unit for beverages and beans. And that glass, formed as a jar or a bottle, became the receptacle for foodstuffs galore, whisky included. It was the development of the glass bottle and its flat bottom that permitted aged wines at last to be appreciated, wine till then having been stored in amphorae or bulbous-shaped, standing containers, upright, and fizzily young, before taking on the sourness that denotes France’s vin-aigre, or vinegar.

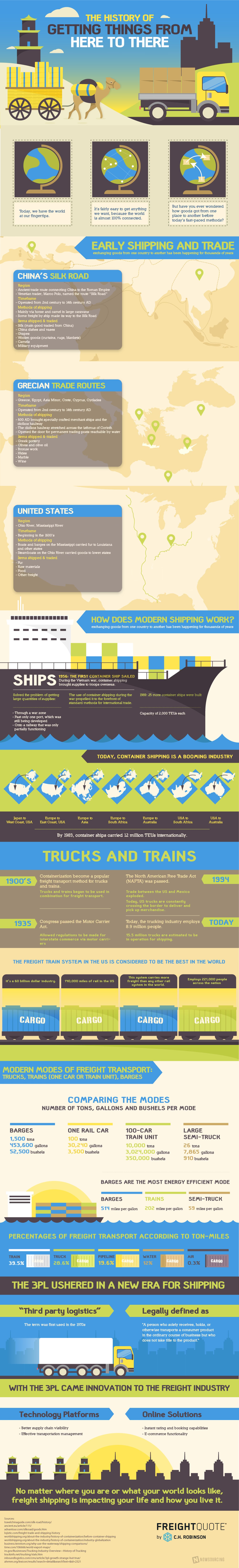

C. H. Robinson is a long-established (1905) carrier (now they’re called freight shippers or logistics firms) and their Freightquote website contains this interesting summary of freight transport across the ages, starting in 4,000 BC. I find it enlightening and not too wearying to read in its fullness. It ends with a salutary and refreshingly frank message, however: No matter where you are or what your world looks like, freight shipping is impacting your life and how you live it.

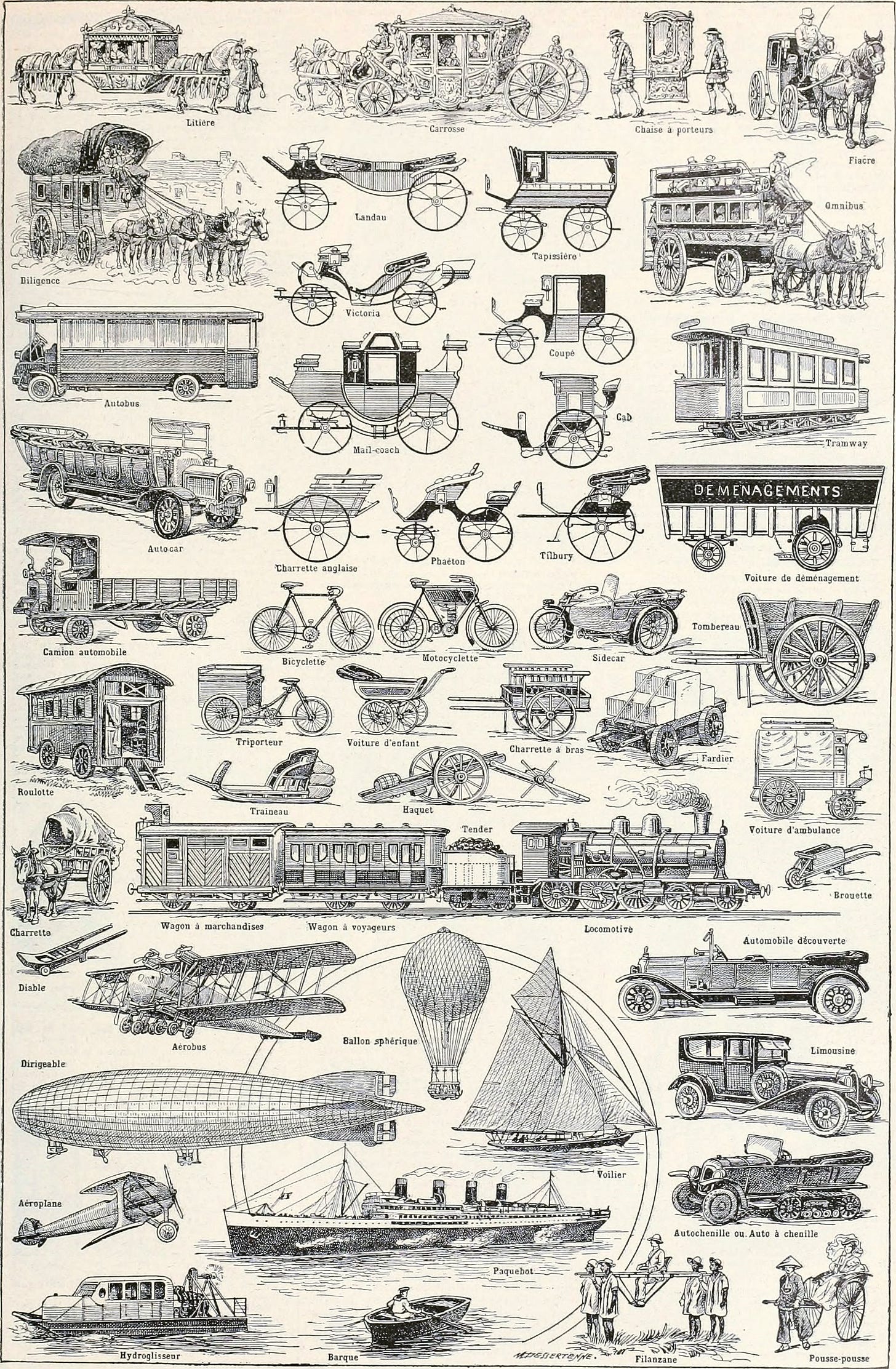

When we look at how goods used to be transported (for instance, look at the graphic from the French-language Larousse encyclopaedia of days gone by, below), you can see how mass (and individual) transport was very much a matter of single packages being loaded into wagons, trans-shipped with sack trucks, or bulk-conveyed in hoppers and tankers, such as with ore, coal, milk or oil.

None of these modes of transport will now be constructed in anything like the same proportion of wood, cloth or even, in some cases, metal. Each of these conveyances now contains a large quantity of plastic; although not all plastic is as perishable as that which you’ll find wrapped around your lunch, and whilst great advances are being made in the amount of plastic that can be recycled, whether by machines or, in some cases, by microbes, even the most optimistic recyclers concede that the mountains of plastic waste that need to be dealt with (and production seems only to be increasing) will hardly be dented by our current rate of repurposing.

I used to take solace in the fact that the plastic that was in my possession on a more or less permanent basis (as opposed to being wrapped around my foodstuffs) had a lifespan that was greater than my own. But this is now proving a fallacy: whereas I take pride in working wood with planes that belonged to my grandfather, and turning my garden with spades that were my father’s, I have storage boxes of only 20 years’ vintage that now crumble to pieces when they are knocked or lifted; kitchen utensils prove to be of very short lifespans; agèd office aids, such as folders and the like, easily tear and disintegrate when utilised, their resilience lost to time and sunshine. It pains me, within a last furlong towards retirement, to replace such items, but they were purchased in the first place in order to fulfil a need, and their disintegration has not caused the need to disintegrate with them.

It is this that is the most galling: it is quite one thing that we package goods in plastic, only to rip it off at the goods’ destination and bin it, its purpose then served; and quite another to purchase plastic items that often cannot be found in wood or in metal at a comparable price—that complaint again!—but whose ability to endure the ravages of time, once thought unsurpassable, is now found to be so lamentably lacking.

Many stevedores and wharfingers will have been given notice when the container made its appearance in 1956, as the world moved towards abolishing the common carrier status of railways and post offices. Individual shipments in barrels, crates and boxes simply cost the Earth to transport, and the container is the ultimate saver of time, effort and cost in terms of global shipment. But the plastic now resorted to as a part of the money-saving solution for the mass transport of goods, be they “fancy” or essential, is itself now to a certain degree costing the Earth, as well as many of the species that live upon it.

Plastic has two big problems: its limited lifespan; and its eternal lifespan.