The price of safety; the greed of the gatekeeper

Gays exploited in Kenya by people there to help them

Image: Kakuma Refugee Camp and Kalobeyei Integrated Settlement, from the UNHCR website.

It’s 25 years since Matthew Shephard was murdered in Wyoming, and, since then, Uganda has enacted a law, and, soon, Kenya will be enacting one, to make being homosexual a capital offence. Why is Africa so beset with anti-gay laws?

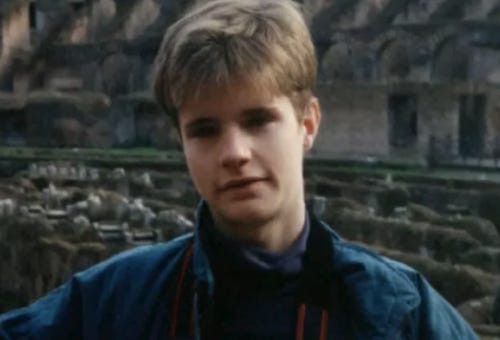

Image: Pink News. Matthew spoke Italian; here he is at the Colosseum, in Rome.

This article is dedicated to the memory of

Matthew Shephard (born 1979, murdered 1998) and of

Edwin Chiloba (born 1998, murdered 2023),

and to the future of Bartholomew, wherever he is now.

This piece is not about Matthew, simply in memoriam. Instead, it’s about Bartholomew, whose name has been altered.

Kakuma: a town in Turkana county, north-west Kenya. Population 65,000, making it the 52nd-largest town in Kenya. Kenya is in eastern Africa and, before it was known as Kenya, it was a part of the British Empire called British East Africa.

In 1963, Kenya was granted independence and it started to rule its own affairs. Laws that were in force at independence remained on the statute book until Kenya’s newly appointed parliamentarians could decide whether they needed changing, needed repeal, or were in fact just dandy.

The laws changed and repealed are not important in the present context. However, one law in particular falls into the last category: just dandy. It’s the 1897 provisions contained in the Penal Code by which acts of indecency between males are proscribed and punishable by imprisonment. Most Kenyans seem to like this prohibition, and are vociferous in maintaining it as law. It is an aspect of colonialism embraced not only in Kenya but in many other former British colonies. It is a policy that has even been adopted post-independence in former French colonies, such as Senegal (former French West Africa), which introduced anti-gay laws six years after becoming independent.

What the British exportation of its 19th century moral code brought to Kenya, as it would be, and Uganda, then a protectorate, was a law against being homosexual. But it didn’t stop there: it has in modern Kenya and Uganda been used to persecute outliers of society, to taunt them and belittle them, to beat them and even to murder them in lynch parties. For example, the fashion designer Edwin Chiloba was lynched in the Rift Valley some time between 1 and 6 January 2023.

The European Union, which channels large sums of aid money to Kenya, encourages the Kenyan government to take a more lenient stance on homosexuality, but Kenya’s politicians, courts and laws remain adamant on the whole, and large swathes of the Kenyan people engage in virulent outcries against gays; they voice opposition to being gay and proclaim “God doesn’t like it.”

God is a big presence in Kenya, as He is everywhere. But, in Kenya, His voice is given much amplification on matters that leave one feeling God approves acts of discrimination, hatred and murder; Kenyans are less publicly committal about whether they believe God dislikes those things.

Homosexuality is illegal under Kenyan law and, under Ugandan law, it is a capital offence (and may soon be that under Kenyan law). Uganda is a land-locked country, and some gay men who suffer persecution there seek refuge across the border in Kenya, where the UNHCR runs a refugee camp, at Kakuma. Some UNHCR officials at Kakuma take advantage of their position and Kenya’s laws to extort money from gay men who end up there, so I have learned from Bartholomew.

I believe that that is wrong. Instead of militating for a relaxation of Kenya’s laws, these individuals take advantage of the legal situation to feather their own nest. I also think it is possible that extortion, the reason why homosexuality was decriminalised in Britain, may be why, on the contrary, homosexuality has been criminalised in Africa. See my article:

Homosexuality and money-laundering

Actor Peter Cushing in a 1968 portrayal of the character Sherlock Holmes, eyeing the jewel known as “The Blue Carbuncle”. Thanks for reading The Endless Chain! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work. The fraudster and the conjuror both rely on one thing: deceptive sleight of hand. Whilst conjuring justly enriches its audience with i…

And I think that the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and the Kenyan government should take action to stop such practices.

The adamant upholding of the 1897 statute

The 1897 provisions in the Kenyan Penal Code that outlaw homosexuality read as follows:

Penal Code of Kenya, section 162

Unnatural offences

Any person who (a) has carnal knowledge of any person against the order of nature; or … (c) permits a male person to have carnal knowledge of him or her against the order of nature, is guilty of a felony and is liable to imprisonment for 14 years…”

Penal Code of Kenya, section 165

Indecent practices between males

Any male person who, whether in public or private, commits any act of gross indecency with another male person, or procures another male person to commit any act of gross indecency with him, or attempts to procure the commission of any such act by any male person with himself or with another male person, whether in public or private, is guilty of a felony and is liable to imprisonment for five years.

In 2019, the Kenyan High Court ruled that these two provisions are not discriminatory, and that they therefore do not fall foul of the Kenyan Constitution of 1963. I think that that is wrong. I think that, barring any additional line of argument, a court errs when it finds no discrimination in a legal provision that purports to treat men in one manner and women in another (in the case of section 165; section 162 outlaws the procuring of unnatural acts against men and women) or that prima facie runs counter to article 7 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, article 26 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the UN’s Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action.

However, I recognise that the task before the High Court in its decision was not to test the validity of sections 162 and 165 of the Penal Code against these UN instruments, to which Kenya is nevertheless a signatory, but to test them against Kenya’s own Constitution, because, sadly and patently, it is perfectly possible, if contradictory, for the constitution of a member state of the United Nations to differ greatly from that member state’s stance as voiced in relation to UN-adopted instruments.

In dismissing the petition, Kenya’s High Court found (paras 295 and 296 of the judgment):

The substance of the Petitioners’ complaint is that the impugned provisions target the LGBTIQ community only. If we understood them correctly, their contestation is that the impugned provisions do not apply against heterosexuals … [O]ur reading of the challenged provisions suggests otherwise. The language of section 162 is clear. It uses the words “Any person.” A natural and literal construction of these words leaves us with no doubt that the section does not target any particular group of persons.

This is reasoning that has been dismissed elsewhere as specious. A crass example: prohibiting any person with a limp from theatres, on the ground that a person with a limp would, in an emergency, block the path of escape for able-bodied persons. The disabled limp, so the prohibition is against the disabled. Defining a practice that itself defines a group and saying anyone could indulge in the practice is disingenuous and, elsewhere, has failed as a legal argument. But not in Kenya.

Interestingly, the High Court of Kenya dealt with a further case in relation to discrimination in 2022. In 2019, a recommendation had been made to the country’s then president, Uhuru Kenyatta, concerning the appointment of 40 judges to the nation’s judiciary. The President had approved all but six of the appointments, and the case before the High Court concerned what was described as the six’s reasonable expectation that they would be appointed and the incompatibility of the President’s refusal with the tenets contained in the country’s Constitution. It is generally held that this judgment was right in finding that the President had indeed acted unconstitutionally.

Clearly, the High Court is able to distinguish discrimination when it sees it, more especially when it sees it exercised against its judicial brethren amid collegiate intakes of outraged breath. But, when measured in the manner in which a colonial law, one which the colonial power imposing it has itself meanwhile repealed in its own jurisdictions, might constitute discrimination by reference to the same national Constitution, it raises not a murmur of demurral. The court’s inability to appreciate that sections 162 and 165 Penal Code are discriminatory has led some to conclude that Kenya’s High Court is itself discriminatory in how it perceives discrimination.

The wording of section 165 clearly treats men as the mischief in point. There exists no analogous prohibition against women. It may not exclude women expressis verbis, but it does so a contrario: women are not male persons. Sexual orientation is a factor given in article 7 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights dated 10 December 1948:

All are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimination to equal protection of the law. All are entitled to equal protection against any discrimination in violation of this Declaration and against any incitement to such discrimination.

The colonial-era provisions outlawing homosexuality deprive homosexuals in Kenya of equal protection under the law, and that certainly sounds discriminatory. As recent legislation in Uganda has shown, homosexuality is an emotive topic in eastern Africa, and the tightening there of anti-gay laws can be viewed as an unstinting effort to stonewall the statutes’ revered standing in law in order (purportedly) to repel all and any argument as to their discriminatory effects.

The de facto invidious position of gay men seeking refuge from mortal danger in surrounding countries

Kakuma Refugee Camp was set up by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in 1992, since when it has grown to a population estimated at 300,000 (which will likely grow in the light of the conflict that erupted in Sudan). These persons are offered intake, support, assistance, resettlement and protection at Kakuma. They hail from a number of directions, including countries in which, as homosexuals, they face beatings, rejection, violations of human rights, attacks, ridicule, death, rape and other ignominies.

The UNHCR extends a helping hand to refugees from sexual persecution, but it does so on the territory of a country that practises such persecution. Who, then, owes the refugees a duty of care?

The prime duty of care owed to the Kakuma refugees is owed by either the Republic of Kenya or the UNHCR. It is on Kenyan territory that Kakuma stands. However, in this duty, Kenya fails: it maintains statutory provisions that would punish the homosexuals in Kakuma. The only thing that stands between the Kakuma refugees and the Republic of Kenya’s criminal justice system is the UNHCR. It is thus a crucial role that the UNHCR plays in protecting refugees.

No refugee camp is erected in perpetuity: it seeks to succour to an immediate need and, over time, its residents should be resettled or otherwise accommodated and, once the source of the refugees’ flight is resolved, it should close. But Kakuma is not set to close: it just gets bigger. The conflicts that induce refugees to come to it are of the long term.

Resettlement is an option for refugees but it is not a right that they can command. They may apply and wait until a suitable opportunity presents itself. The UNHCR’s role is therefore not only crucial, but it is also one in which, de facto, it exercises a broad range of discretion. Simply put, if the UNHCR chooses not to resettle any particular refugee, then it can freely decline to do so.

What is more, it is conceivable that persons working within the UNHCR might recognise a profit opportunity in declining resettlement to any given refugee until such time as a facilitation payment might be remitted to him or her. Thus, they might not simply decline to resettle refugees but might engineer circumstances to procure a situation which serves their own personal best interests.

The Kakuma gay refugees complain that they are the target of abuse by certain parties, which include fellow refugees not identified as homosexual, persons who do not reside in the camp but in the town of Kakuma proper, the Kenyan National Police, who bear responsibility for law and order at the camp, and, possibly, other parties unknown (confrontations rarely lead to the culprits being identified). When abuse is complained of, the frequent response from the UNHCR is reportedly either zero or, at best, of little to no effect in preventing or stopping the abuse.

It is perhaps understandable that the UNHCR cannot oblige a resolution to reports that reach them of abuse given that power to take action against that abuse lies not with them, but with the National Police. The police’s prime function is, unlike that of the UNHCR, not to provide protection to refugees, but to ensure that people abide by the laws of Kenya, both inside and outside the camp.

Hence, there exists a conflict of interests as between the Kenyan National Police and the UNHCR. Given the camp’s institution in 1992, it might be thought that the UNHCR would have negotiated some kind of settlement procedure or enduring solution that might resolve the ostensible conflict of purviews. None has been forthcoming in all of 31 years of the camp’s history. There was no great hindrance to the camp being built when the need for it became clear; however, any solution to this dichotomy has certainly proved itself not immediate.

Why is UNHCR incapable of resolving the protection and abuse aspects of its housing gay refugees?

Why is homosexuality against the law in Kenya? There are several obvious answers: the British imposed the law, and it has never been repealed, even if the British have repealed similar laws in Britain. Kenya is in fact at liberty to keep the law.

Why did Britain repeal its laws? There are good reasons for repealing laws of this sort, not least compliance with certain UN instruments, as referred to above. They encompass liberal compassion, freedom of expression, freedom from abuse, equality and so forth. However, one major consideration prompted decriminalisation in the UK: blackmail. Homosexuals were susceptible to it because their proclivity was a criminal offence, which they sought to conceal; and so they paid the extortion demands of those who threatened to reveal it. If it was to stave off the societal threat of blackmail that homosexuality was decriminalised in the United Kingdom, could it be one reason why it hasn’t been in Kenya?

Notwithstanding the importance placed in Kenya on human rights, the right to be homosexual is not among them. Instead, in that field, Kenya maintains laws that not only put men in prison but that also send subliminal messages that are all too readily taken up and acted on by the Kenyan population; they condone abuse of part of the population by other parts of that population, and even give an implicit nod to extreme acts, such as lynch parties. The law against homosexuality is potentially a highly powerful leverage tool against gays, which could be used both to acquire power and to exercise it.

Figures in politics and religion in Kenya frequently make condemnatory public statements against homosexuals. While these don’t explicitly encourage violence, they are nonetheless far from benign, and are occasionally acted on as if they were malignant, few efforts being deployed to ensure that listeners are disabused of that interpretation.

Why, then, is UNHCR incapable of brokering a favourable settlement in gay refugees’ relations with the police? It has possibly tried and failed. It has no leverage over the police, who themselves are technically bound under their duty to the law. However, the failure of any such endeavours is also consistent with there having been none made. It is even possible that the UNHCR made a positive decision to not make them. Is that conceivable?

When a gay refugee at Kakuma is so frightened at being abused and beaten, it can be expected that they will request resettlement. Resettlement is, after all, a mandated duty of the UNHCR under its constitution; it’s what they do. But there is no means of enquiring why, in any given case, a person’s request for resettlement might be turned down.

Bartholomew was at Kakuma and offered the following anecdotal evidence of why not. Refugees eager for resettlement are desperate, perhaps even very desperate and the ease with which assailants of gay and lesbian individuals can access the camp suggests that it lies within the power of the UNHCR and/or its officers to augment or diminish refugees’ desperation to apply for resettlement: rationing of food; failure to respond to complaints of ill treatment from refugees; a blind eye being turned to police actions targeting queers; and even active encouragement of abuse, of police action, or refusal of service from traders at the camp, and other inconveniences. These could all conceivably stand to reason and crank up levels of desperation. What is there to be gained from this?

How could UNHCR administrators procure gain from refugees’ desperation?

The UNHCR’s crucial role in relations between refugees and the state of Kenya imbues it with the ability to massage the conditions in which refugees live. It has a duty of resettlement, but it is essentially unpoliced: it happens when it happens. When filling in an application for resettlement, Bartholomew was told by the UNHCR official helping them that their application could be the start of a process that sees them resettled to Ontario, Canada.

Canada has a tradition as a generous third country that offers favourable welcomes to African refugees in need. Bartholomew was furthermore told a success story to back up that claim: about a refugee from Kakuma who was then living in Canada.

Surely there must be more than one? Unless this particular administrator has seen only one? Is that odd? Maybe they’re new. This incidental information certainly had the effect of instilling in Bartholomew the viability of what was being proposed.

But he was then told it was only viable if a payment was made. A trusted contact at the European Union assures me that refugees, of all people, do not require to make any payment to be resettled: sponsor and donor countries pay to facilitate this process.

But Bartholomew was asked to stump up a sum he didn’t have, so he asked me. I asked my trusted friend, who had no response. A sum of 70,000 Kenyan shillings, payable to the administrator. That converts to around 520 euros. It is a tidy sum, but not a treasure trove. Most people could find 520 euros if they really needed to, and refugees generally really need to. However, they’re not like most people, since they live in a camp and have nothing, which most people, even in Kenya, don’t.

Moreover, 520 euros may or may not sound like much to a single refugee, but it mounts up when an official demands it from every refugee who is resettled. That’s not a tidy sum: it is an income flow, pocketed directly, untaxed, one that offers—despite being given—no guarantees, and one that—if proof were needed—proves that, if camp conditions are indeed manipulated— it’s a tactic that works.

It creates enough desperation to impel refugees to clamour for resettlement from gatekeepers who may have engineered their desperation in the first place, only to then cash in by demanding payment to do what they’re paid to do by the UN and the nations of the world.

What is more, because resettlement is thereby shown and proved to function, even if it is greased by the oil of corruption, the outside world views the UNHCR as a properly functioning body. Since the UNHCR’s reputation as an efficient resettled of refugees is thus evidenced, other refugees view the UNHCR as a valid saviour in their hour of need, and flock to it, only to be put through the same extortion scheme. It’s certainly a possibility.

Conclusion

The posit is this: those working under the aegis of an organisation that succours to the aid of the needy in Kakuma exploit the needy as a raw material to augment their own incomes. Simultaneously, their positions are salaried using funds from UN member nations, and they ensure the success of the UNHCR, whereby it attracts replenishment of its “stock” of refugees, whom they then ensure are desperate enough to clamour for resettlement. Refugees do benefit by going to Kakuma, just as refugees benefit from heading for the English Channel; but, as with the small boat traffickers, the refugees not the only ones to benefit.