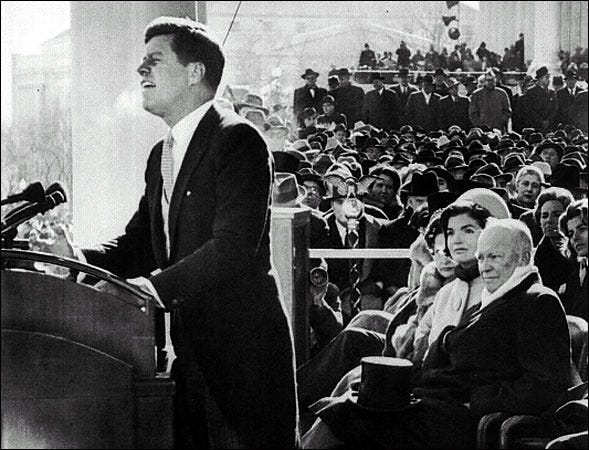

Image: the inauguration of John F. Kennedy.

The primacy of politics supposes that, in a democratic election, the electorate confers a mandate on the winner to implement their manifesto. The manifesto that is thereby implemented prevails above and beyond all considerations of whether it is lawful, moral, in accordance with accepted wisdom, convention or human rights. What counts is the mandate that the people have conferred, nothing else. That is the primacy of politics, and it is attractive. Even if it is flawed.

It is a reality of politics that the winner should get to implement their policies. That has been a constant of politics since democracy ever saw the light of day. But it is also a constant that the prerogatives of the enfranchised to elect a ruler who may legislate without regard to the disenfranchised have to be limited by a framework set down in law. The law, which is there for the protection of all including the disenfranchised, cannot be set aside in order to enact the will of the enfranchised. Yet that is what is being pleaded by the American government, and by other governments around the world: that the interests of politics as contained within the mandate conferred by the electorate authorise them to enact policies that fall foul of the rule of law, in the interests of the primacy of politics. It’s the reason why Marine Le Pen is crying that the French courts have handed down a political, and not a legal, judgment; it is why the government of Hungary is welcoming Benjamin Netanyahu despite being under an obligation to enforce the ICC’s warrant against the man; it is why the US government has ignored orders issued by an American court to return Venezuelan refugees to US territory. Politics prevails over law.

It is interesting in these early days of seeing this being brought to fruition that governments are nonetheless seeking refuge in the law to justify their breaking of it. After all, if Mr Trump wants to deport Venezuelans to wherever, then why does he resort to citing the Alien Enemies Act 1798 at all? Why does Orbán not simply ignore the ICC warrant against Netanyahu without adding that Hungary is going to withdraw from the Rome Treaty anyway? Why don’t they simply come out and say it plain: politics now prevails over the law, because the people have mandated us to apply that as the new reality? Perhaps because it stumbles at a few first hurdles: the validity of the purported mandate that is given, for one; and, for another, answerability for the consequences of the manner in which the supposed mandate is implemented, i.e. none, not even to the deemed electorate on which the mandate founds, let alone those who did not vote to confer the mandate at all. Even in a world where the primacy of law applies, the law is answerable for its mistakes; but the primacy of politics avers that politics lacks any duty to answer for policy implementation. It is that which makes the primacy of politics tantamount to totalitarianism or, in the current parlance, fascism; and what compounds that conclusion is the fact that the mandate supposedly given can be hard to relate to the acts implemented pursuant to it, the mandate soon devolving into an authority to do as we want.

The citizen is left with a stark choice: to fight for the ideal that they feel they share with their fellow citizens in terms of the rule of law; or to acquiesce in the new reality. This essay attempts to sketch out some of the angles from which one might assess what is idealism, and what is realism.

Life is a tussle between that which is real and that which is ideal. During our hours of sleep, and unconstrained as it is by the real, the ideal has free rein (even if it doesn’t always avail itself of that fact). In our waking hours, reality constrains. It constrains how we act, whether through its laws, its being, its threats or its illegalities, and—perchance—its ideals. If asked to name our ideals, we would no doubt all draw up lists and form models and prototypes of which we were at one and the same time assured in our own minds whilst being certain they differed from those of our fellow man. It is this dissonance between our ideals and our reality that confounds the ideal (and perhaps also confounds the reality), in part because of our failure to understand what an ideal is even permitted to be. We cite the ideal as pie in the sky, as far-flung impossibility, grounded in pure fantasy. So unattainable do we view our ideals that we reject them before we have so much as uttered them.

A realist is therefore somebody who lives in a constant interaction between themselves and reality. Whilst their actions may be governed by certain realities, including law and a finely balanced view on law’s finality coupled with a somewhat cruder evaluation of the chances of being caught, the reality that governs us is likewise one that allows of its own governance by us. In the ideal world, the idealist conducts themselves in like manner to that in which they are governed; being ideal, the notion of predominance must perforce be absent. Predominance is something that perverts ideals, for it cannot be anyone’s ideal for some to be oppressors and others the oppressed. An ideal world in which there are oppressors and oppressed can only exist within the perverted rules of a game of sado-masochism. Perversion—the wilful change of a state of nature—is therefore an abomination of nature and since nature is what we were put on this world to rise above, the very definition of our existence here on earth, our calling—our ideal—as a race is to strike at the perversion oppression when we recognise it for what it is. That includes in those moments in which we recognise that it is we ourselves who are oppression’s beneficiaries. Alas, so much for idealism.

I can cite three phrases that give expression to realism and idealism and that, over time, have proved to be notorious double-edged swords. They are:

the survival of the fittest, the phrase by which Charles Darwin summarised his theory of evolution: that a given species or type which proves itself best suited to living in a given location, environment, climatic conditions, etc. will have adapted to those conditions and therefore have survived, and others will have gone into extinction or been lost to posterity. They survive who are best suited to survival, i.e. the fittest for survival;

charity begins at home; today, a large part of the misconstruction stems from the common association between charity and the act of giving, generally of money, or of time and effort, as far as volunteers are concerned, and not as an expression of what Saint Paul intended: charity speaks not to the act itself but to the spark that impels it, which is love, a word that, in turn, is often misunderstood. William Shakespeare’s works contain the word with some ten to fifteen shades of meaning. That’s quite a lot and, on one view, it is perhaps to be regretted that the English language has proved itself less resourceful in finding modes of expression for the term than, say, the Tahitian language, which reportedly has thirteen words for the concept. On another view, it is precisely the word’s ability to be construed as one thing by one person and as something else by another that is its allure, even in the marriage vows of to love and obey or, in some versions, to love and honour. Is there a difference between love and honour? You might like to consider the contrast between Jesus’s two commandments in Matthew 22:37-40, and the fifth commandment handed down to Moses (Exodus 20:12);

ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country. The phrase formed part of the inaugural speech of John F. Kennedy as president of the United States of America on 20 January 1961. It’s not unlike the invocation given when one becomes a member of a club—will you simply play golf here, or will you contribute to the club’s community? It’s an invitation for the citizen to consider their role, their interaction, with the greater whole, with the nation itself. It does not rule out self-interest; but it invites self-sacrifice. The self-interest that stems from the governance of reality; the self-sacrifice spurred on by devotion to ideals. Which of these will maintain the upper hand at a given time differs according to the individual and the circumstances that surround them. It will be easier to eschew the demands of the nation in times of prosperity and peace; it will be harder in times of peril and conflict; and whilst the individual is cognisant of the fact that, ask though he may, his country may refuse his request, and that the request of the country may not be so easily refused by him, the invocation itself is phrased slightly differently: it is not the citizen’s duty to respond positively to his nation’s request for succour, rather it is his proactive duty to ask what succour he as citizen can provide to his nation.

Like all things Kennedy, a certain controversy surrounds these words, namely whether he wrote them. Whatever Kennedy was, he was not The Manchurian Candidate—he was not presented with a speech and told, “Here, read this.” So, the conclusion by some authors that the speech was a close 50/50 collaboration between the president-elect and his speech-writer, Ted Sorensen, is likely to be on the money. Small changes were made to it in the final minutes before it was delivered, notably preventing aggression in the Americas was changed to opposing it. That’s a small word change for a man, and a giant leap of syntax for the CIA, who likely paid no heed to it.

Does it matter? Does it matter who wrote it? The hallmark of a singer-songwriter is that the heartfelt words that come from their mouths came also from their hearts. There is an authenticity to the song as sung having been written by the hand that strums the guitar. Yet, there are singers who can adopt a song written by someone else and make it their own: the song written by a third hand takes on personal meaning through association of the singer. Frank Sinatra’s My Way is indelibly associated with the man, but stems from a French song with a quite different lyric entitled Comme d’habitude, adapted by a Canadian singer-songwriter, Paul Anka, inspired by a dinner he and certain members of the mafia had with Sinatra, at which the latter said he wanted to quit the business. Sinatra had great success with his 1969 recording of My Way, but his daughter later confessed that he came to detest the song like something he couldn’t shake off his shoe. It’s pure conjecture, but, barring any other explanation for his ultimate dislike for the song, could an enquiry into what, exactly, he was wanting to quit at that dinner table with Paul Anka et al. offer any clues? Apart from that, at what point does one have enough regrets to actually mention them?

No. It doesn’t matter. We don’t run our lives according to the sentiments of a song, regardless of who wrote it, still less the sentiments expressed in a speech, no matter how imposing the speaker, or how inspiring the words used. In that moment, the words inspire. Then the lights go up, we gather our coats and take the bus home.

Readers thus far may already be thinking about their metaphorical coats and checking their metaphorical bus schedules. Is that your ideal? To walk away when the questions get too difficult? Hang around, I have a few more.

The application of man’s ingenuity to our world is selective. We overturn nature’s determination of who the fittest are and, hence, whether they should survive, by creating artificial conditions that pre-determine a particular type of fitness for a particular type of purpose. Not nature shall decide the fitness for purpose of a species, but the species itself. Some contest whether Charles Darwin was even right in terms of what he intended. In terms of what he didn’t intend, he might as well have said brute force will always win the day.

According to Wiktionary, the phrase charity begins at home means one should help the people closest to oneself before thinking of helping others. I think that that definition is somewhat limiting, because it’s generally construed as meaning help yourself before helping others. I don’t want to appear uncharitable, but it leaves unanswered where you yourself stand in the hierarchy of charity comprising: you, others close to you, others less close to you.

Each of these three phrases, each a double-edged sword, is attractive to two opposed viewpoints. If one party assumes a position of power and then uses that power to oppress others, they can argue that they are thereby the fittest to wield that power. I doubt whether charity beginning at home was devised as a means to persuade the overly philanthropic to shower their grace on those they know rather than those they do not. Rather, it looks more like an invitation to shower it at all, and not keep it for oneself. What then remains to be considered is what home betokens, if that is where charity should begin. Can it be taken as translating to America first?

Gloire immortelle de nos aïeux, sois-nous fidèle, mourons comme eux, et sous ton aile, soldats vainqueurs, dirige nos pas, dirige nos pas, enflamme nos cœurs!

The Soldiers’ Chorus from the opera Faust by Charles Gounod, libretto by Jules Barbier and Michel Carré. Inspiring words indeed.

Immortal glory of our forebears, be true to us, let us die as did they, and under thy wing, victorious soldiers, direct our steps, direct our steps, inflame our hearts!

If ever a country asked of its citizens an act in its behalf, this was it. It is called the ultimate sacrifice because, aside from confiscation of the citizen’s entire goods and chattels, what else can he offer to his nation? Or, more exactly, what else can his nation take from him?

Faust is a well known story, put onto the stage in English by Kit Marlowe in 1592 from an amalgam of traditional stories and folk tales that had been bandied about since time immemorial and in which the protagonist’s name is Johan Faust (Johannes Faustus, or John Faust). Wolfgang von Goethe tied the character down in his own version of the story in Germany in around 1806, whose first name is Heinrich, or Henry. If you’re unfamiliar with the story (the man who sells his soul to the devil), you may wonder why there is even a soldiers’ chorus in the opera. In Goethe’s version, on which the opera is closely based, love plays a large role: Faust has been busy selling his soul, in which he trades his love of mankind for love for himself. Meanwhile, his friend Valentin is shortly to depart for the wars. Before doing so, he commits his sister, Marguerite, to the care of the Lord. Faust falls in love with her, eventually gets her with child, which she drowns; she is convicted of that murder, whereupon Valentin returns from the wars along with his comrades (to the strains of the Soldiers’ Chorus). There is a strong implication that those who go off to foreign parts in order to kill in war commit less sin than those who stay at home and betray promises. Barbier and Carré only underline that sentiment with these words: the spirits of our forebears must be faithful to us and egg us on into the battle: we ask what we can do for our country, because our ancestors instil in us the will to do so. And, if they don’t, the country certainly will.

Thus is it a fairly common feature of warfare that the reason we engage in it is at least marginally cited as being the fact that our forebears engaged in it as well. In the 1989 film Born On The Fourth Of July, after a visit to his school by a recruitment officer, the character of Ron Kovic argues with his friends that serving in the Vietnam War is his way of playing his part, just as his father had done in the Second World War. After he wrote the autobiography on which the film was based, Kovic said, “Convinced that I was destined to die young, I struggled to leave something of meaning behind, to rise above the darkness and despair. I wanted people to understand. I wanted to share with them as nakedly and openly and intimately as possible what I had gone through, what I had endured … not the myth we had grown up believing. I wanted them to know what it really meant to be in a war.”

Given what a geopolitical game-changer war is, it is surprising to consider the fact of having previously been engaged in one as a reason—or at least a conscience-salver—to engage in yet another one, especially if the feeling at the end of the previous one was thank God that’s over. The reasons why wars are engaged in differ, but not the reasons cited by governments to persuade their citizens to fight them. Just as they have been since the age of chivalry with its knights in shining armour, they continue to be honour and the glory of our forefathers. The victors can add their medals to the combined national honour; the dead can add their names to the roll of honour. The nation, for its part, lives to see another war.

Wars are reality, even if they may seem like a nightmare, even if we cannot believe our ears. They hardly fall within the concept of an ideal, since by definition they betoken a winner and loser and, as I state above, no ideal can have winners and losers. An ideal must achieve a state of perfection for all parties. It’s a state in which your own existence cannot detract from, but may contribute to, your and your fellow humans’ existence. It’s a state in which the deleterious effects of our acting are non-existent or, if they are subsequently recognised, action is taken to abate them. It is for this reason that ideals are as good as written off before they are formulated. You can’t help everyone is taken as a cue to not help anyone. So multifaceted are the demands that are placed upon us that we do what we call prioritising. Except that the harm we cause through our actions gets substituted by money considerations, and that is not always the ideal way to define an ideal. If it were, the ideal way to do business would be to steal everything. Which is what capitalists essentially do, define capitalism how you will.

The stepping stones that lead our way towards any ideal we might consider, whether feasible or otherwise, are called principles. A principle can fail, and it can be confronted along its way by another principle, of equal value but opposite effect. Our thinking minds were bestowed upon us precisely to be able to reconcile conflicting principles, because our ability to pervert nature and our duty to rise above it obliges us to reconcile our contrary actions, even if it poses a challenge. I’m really not certain whether money can qualify as a principle. The ruthless hunger for it seems more akin to a constant condition for acting at all. It’s only by removing money considerations that true principle gets to play its cards, that any hope of achieving an ideal can be cherished.

As I state above, when we act in relation to reality, we change reality. In Newtonian terms every action has an equal and opposite reaction. There is a strange dynamic at work with the current spate of US import taxes: they are a tax on consumers, so they are a tax on American consumers. Foreign countries that export these goods are considering imposing tariffs of their own on American goods, and that poses an interesting question: if America wants to tax its own citizens, why should that have the effect of propelling other countries to tax theirs? Of course, it has to do with the resulting prices of goods and how they stand in competition to each other in the market in question (if it even has to do with that, in fairness), because if the concern is not to prejudice home-grown products against imported products, the argument seems to be that many of the products exported to the US are exported there because the US isn’t able to make them themselves. And we have seen how, when something is unobtainable, like an egg, you can jack its price as high as you want, people will simply stump up. Not reacting to an action is also a possibility.

In a recent essay by Julia Christ entitled Faust, Breaking Bad and the Jews: modern powerlessness and acting out, the writer examines the reality that was faced by two quite different protagonists: Johan Faust, already mentioned, and Walter White, the protagonist in the serialised TV story Breaking Bad. She draws a surprising, but logical, conclusion: that when we act in function of our own purported reality, we achieve a differentiation from our fellow man that leaves as our sole exit either suicide or domination. Reconciling our own reality with that of our fellow members of society becomes elusive. So, the reaction that our actions provoke becomes a dissonance because our reality does not accord either with the reality of others or with our shared idealism.

That may be hard to take in, but a moment’s reflection will confirm: when we act autonomously in relation to reality as we perceive it, we change reality as it applies to us. Because all of society is doing that at the same time, we end up with a conflict, a multitude of conflicts, which imply that either a resolution will come from our domination of others’ realities, or we will substract ourselves from the conflict, through suicide.

In relation to Faust, Christ considers his translation exercise of the New Testament, and his mental wrangling over the word logos: in the beginning was … what? We know that the Authorised translation is word but, in Goethe, Faust considers whether we need a word at all: in the beginning was a deed.

The deed presupposes a subject, and therefore an intention, but it does not depend on a response from reality: it creates it.

…

The deed is a transformation of reality so radical that it creates a new one. This may therefore appear to be a solution to the situation where it seems impossible to get a grip on reality, quite simply because we no longer understand it, we are unable to know it, and therefore even less able to recognize it and feel at home in it.

Whether you subscribe to the ripple effect or the chaos theory, to the extent of that which you can see, feel, hear, smell and taste right now, anything that you do will alter those perceptions and, because what any of us perceives is our reality, then your deeds always change reality, no matter how small the change. The threshold beyond which a minor change becomes a major one is an arbitrary one, which varies day by day, minute by minute, person by person, and is therefore irrelevant to the principal observation as to what reality is.

From there, it is clear that your and my realities are different. And yet we co-exist, I hope, happily, without conflict. So, how do we achieve that? Well, we achieve it principally by not thinking that much about each other. Have no fear, you are in good company, because I pay not a minute’s heed to anyone in particular in many corners of the world. It is something which allows us peaceable co-existence on this planet of ours. But, if someone in a far-flung corner of the world were to launch a missile at my home country, then our realities would converge and, because clearly, launching a missile produces a winner and loser, missile-launching is not an action that falls within the concept of ideal. Instead, our realities collide. But, if you act in such a way as I view as consistent with my own ideal vision of the world, then your act will be in harmony with my concept, and we can therefore continue to co-exist happily.

Without wanting to strain the analogy too far, if we want to escape from acquiescence in the notion that war is man’s natural state and that peaceful co-existence is an ideal worthy of aiming for, then what element of our action will contribute best to its achievement?

We have outlived the age of international law. Its institutions are crumbling: the United Nations, the International Criminal Court, the World Health Organization, the World Trade Organization, the International Court of Justice, alliances with the world’s principal and only superpower. Crumbling like dust. With that dust goes our collective reality. Whatever actions we undertook in our own pockets of existence, these institutions encapsulated a view of the world and its order. They didn’t always agree, not entirely, but we learned to live with their inconsistencies, just as we learn to live with our own. What bound us hitherto to these institutions as well as what bound them to each other was simple acceptance of the principle that warfare is bad: it’s bad for countries, bad for their people, bad for the economy, bad generally; in place of these principles, there is a shift towards a world in which brute force is indeed a valid means to get what you want. You actually need to work for it, or negotiate for it. Politeness probably demands that you ask for it. But what isn’t then given is taken. The unifying force that embraces us all and restrains us from exercising such raw power has existed within the body of international law since the end of the Second World War: its overwhelming influence has been to restrict the extent to which we are able, in terms of Faust, to contract with the devil and, in terms of Walter White, to let the criminal production of a restricted substance provide the justification for killing rival mobsters.

In her essay, Julia Christ sees the rationale for conferring on the individual an adequate degree of autonomy to allow of a satisfying life lived, whilst recognising the need for an all-embracing cocoon that holds all of our multifarious realities together:

When Walter White gets rid of all his routines, sends all the rules that have structured his life to hell, it is because he perceives, at the moment of his announced death which is inevitably a moment when the question of the individual justification of life arises, a contradiction between these rules and what they are supposed to allow individuals in modern societies, namely the autonomous conduct of their own lives. [Her emphasis.]

If we cannot act due to a web of regulation that prohibits acting, except as is dictated by him who sets the regulations, then our freedom becomes meaningless. It offers us a stark choice:

[H]aving reached this point of realization, the modern individual seems to have only two solutions: suicide or the deed that destroys complexity, and puts individual desire in the place of rules.

Christ, as a Jew, pursues in her article the viewpoint that concentrates on Jews as a minority, intellectual, composite part of most societies, and her piece is interesting if you wish to pursue that angle further. But what she homes in on generally is the dangers by which, according to the 1930s sociologist, Karl Mannheim, we risk falling into a similar trap as occurred at that time: reprimativization of our societies, whereby society at large reconciles the fact of being over-regulated in a construct that is overly complex by engaging in a process of restriction of input: not wanting to know (which, Christ argues, is anathema to a Jew). First, reality gets presented as a simplified, over-simplified, version of itself, one that is less complex and therefore more readily attractive to those who don’t want to know, by parties who know what they do want people to know, i.e. the fascists in terms of 1930s Germany. The phobia of interdependencies then drives individuals to place mistrust in their fellow citizens:

it is also the reaction of ultraliberalism, which hyperbolizes the individual and his free will against the laws and rules that bind the different elements of societies and accepts as the only link, always temporary, the deal that he can conclude on the spot and always undo. [Her emphasis.]

Third, a shroud of national culture gets presented as inalterable, and as defining the characteristics of the people who are thereby defined. It’s a neat trick, since when you define people, it is perhaps more obvious to ask them to define themselves, but for centuries we’ve allowed national anthems to tell us what our national culture is, and our ears are still, whether we like it or not, open to such persuasions.

Finally, we have orthodoxy, on which Christ says:

This is the intellectual reaction par excellence when intellectual and scientific elites refuse to investigate social reality, without wanting to give up their prerogative to say “what holds the world together”.

Broadly, Christ invokes Mannheim in order to advance the idea that we are currently in a process by which our complexity will be simplified to the point of gratitude to those who simplify it (having first made it more complex), and either we will hold ourselves to be above the law or national culture will tell us who we are, meanwhile we will cease to make enquiry into factual matters (who wants a more complex input?) and orthodoxy will persuade us that compliance with the new order will assure us our place in it.

The role of the primacy of politics in all of this is to claim, falsely as it turns out, that the mandate conferred by universal suffrage (de iure if not de facto) grants the elected official the authority to usurp the very foundations upon which his democratic electoral win is based. The similes and metaphors that underpin his accession can just as easily be turned to require the electorate to acquiesce in his abuse of them. Because the electorate yearns for a less-complex paradigm within which to exercise their suffrage, they are easily browbeaten into relinquishing their suffrage altogether. They abandon their ideal, and acquiesce in re-forming their reality in line with what they are told to adopt as reality. Failing which, their obvious way out is self-subtraction, which is promised to the resistance in any event. It is the substitution of desire for rules, as described by Christ, that logically gets translated into the primacy of politics (which is simply an expression of desire) over the rule of law (which is supposed to be the limiting framework within which desire is pursued). The result is boundless desire.

Perhaps the new world order is what President Trump and his cohorts in other countries are already bringing into being; but they do not have me on board, and I don’t think they ever will. Because I hold to an ideal, and it is an ideal the pathway to which is paved with sure and reliable stepping stones. I’ll be blunt: idealism may be in vain, but realism will, contrary to how it is commonly perceived, always result in conflict. It is that irony that I want you to take away with you and consider.

You can create a legal system that is broadly idealistic. It’s the kind of structure under which the robber, caught red-handed, offers himself up to the police with “It’s a fair cop.” I am minded of the closing scenes of two movies, in which the detective suddenly tumbles to who did it, and whoever did it is resigned with his hopeless situation: The Taking of Pelham 1-2-3 (Walther Matthau version) and Frenzy (by Alfred Hitchcock; see the clips below if you’re curious). But a fair cop sometimes means police having to run after a culprit who prefers legging it to extending his wrists to be cuffed. Shooting the culprit is the preferred option and police really should be called out more often for the real reason they shoot people: sheer laziness.

It is hard to imagine a justice system that enjoys the respect of lawmakers, law enforcers, law breakers and the law abiding in equal measure. Each of these parties’ realities comes together in the justice system and, in a justice system, each of these parties has to be able to recognise their own place. Justice is an ongoing project, one that never ceases to pose its challenges, one that will never be completed as long as man draws breath on this globe of ours. Because justice is all about redressing imbalances, and you cannot address imbalances in the realm of justice from a position of idealism, because there has already been a loser. It takes great self-restraint for him who now has the upper hand not to want to assume the position of a winner. The ideal in terms of justice must be justice that leaves no winner, because justice with a residual winner is not justice, it is profiteering.

The understanding that love engenders gives rise, almost as night gives way to day, to a sense of justice that imbues a society and leads, sine qua non, to a sentiment of fairness with society generally. Retributive laws, on the other hand, create a society in which retribution becomes a norm for all behaviour, including criminal behaviour.

The justice that governs our shared realities must be made to our shared ideal. Only then can we even start to consider our individual freedoms within that cocoon. It is that one deal that it behoves us to make. But, I fear, now is not the time to make it. We have not lost enough to place us in negotiating mood. We are too prepared for war, and not weary enough of it for peace.

Hi Graham, while I agree with everything you've said in this essay, I think there is one factor that you and most others omit. Since the early beginnings of civilization, 10,000 years ago there has been an unwritten rule that most people overlook: Any Governmental formation requires the majority of its citizens to obey and abide by the laws as written by its 'leading' members.

So long as the majority of citizens adhere to this unwritten rule that particular 'civilization' survives and even flourishes. I makes no difference if the civilization is authoritarian (meaning ruled - usually ruthlessly - by a very few despots and supporters; or 'democracy' (meaning rued by the citizens or their representatives)

If, as the case in my Country (the United States) right now, the 'rulers' [the evil triumvirate of musk-trump-vance] simply ignore or outright disobey any written law from the Constitution on down; the citizenry must either acquiesce to the authoritarians or revolt. Starting tomorrow, I hope, is th3e beginning of our revolt.