by Graham Vincent

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

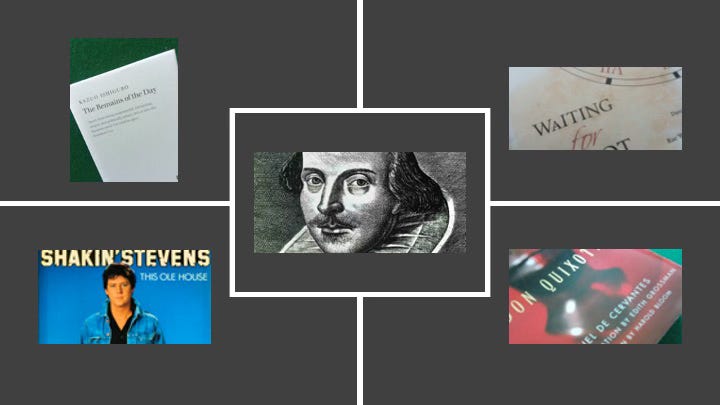

William Shakespeare, a writer of plays

DD, a helper of Cervantes called Shakin’ Stevens

Tramp, another helper of Cervantes called Lucky

Butler, a butler called Mr Stevens

Miguel Cervantes, a writer moving flats

Female Tourist, a tourist with no name

Male Tourist, another tourist with a name he dare not speak. Not after this.

Doubling Chart

Shakespeare, DD or Tramp could double as Female Tourist (with a wig, but otherwise indistinguishable from Male Tourist, whom any one of them could also double).

Cervantes is not actually ever seen, so a stage hand could do him. But they have to speak Spanish, for authenticity purposes.

Or Cervantes could also play the Female Tourist or the Male Tourist, or Butler could play Cervantes.

Technically, Shakespeare could play Cervantes, if he spoke Spanish, and was a quick runner around the backstage area, and also one of the Female Tourist and Male Tourist.

Or, if you’re short, you could get a couple of members of the audience to fill in the Female Tourist and Male Tourist. If there’s an audience, that is.

Licensing

No performance may be made of this play without offering me a free ticket to the opening night and a glass of wine (Beaujolais or Merlot will do) and transport to the venue. And a programme. Signed by the cast and director. And a bag of crisps.

DRAMA IPSA

WAITING FOR THE REMAINS OF THIS OLÉ HOUSE

Scene 1

SHAKESPEARE sits at a high, Bob Cratchit-style desk, on which are a ledger and a glass of red wine. He holds a quill pen. Behind him stands a BUTLER, dressed like a … butler (high wing collar).

The BUTLER is impassionate. Unmovable. Dumb as a doornail.

Calendar behind them, prominently headed up “1600”. SHAKESPEARE has a Birmingham accent. BUTLER has no accent. None whatsoever. Not even a trace.

SHAKESPEARE lays down his specs, closes the ledger, stretches himself and dismounts to cross the stage and lock the outside door. He turns back to his desk and there is immediately a rat-tat-tat at the door. He turns back, unlocks the door and admits the callers, turns back again to reassume his mount.

Enter two men, one dressed like a TRAMP carrying three suitcases and a bowler hat, a noose around his neck, but the rope is short, down to his waist only. He speaks, when he speaks, with a Canadian accent.

The other is DD, who leads, is dressed in DD: double denim. He shakes slightly, all the time. Mouse-brown hair, youthful. He speaks with a Yorkshire accent.

SHAKESPEARE: You’re lucky I’m in.

TRAMP: I’m Lucky.

SHAKESPEARE: Yes, you’re lucky. I’m in.

DD: Good evening, Mr In, man; are you free?

SHAKESPEARE: I’m free. But you’re lucky.

DD: No, he’s Lucky. (Beat) So, you’re In, man?

SHAKESPEARE: I’m in. I’m free.

DD: How did you know he’s Lucky? Have you met before?

SHAKESPEARE: What do you mean, how do I know he’s lucky? He’s lucky because I’m in.

DD: Yes, we know you’re In, man, but … never mind.

SHAKESPEARE: You, with the rope, what’s your name?

DD: He’s Lucky.

SHAKESPEARE: Can’t he speak for himself?

DD: No, alas.

SHAKESPEARE: Alas. Oooh … He needs to put his thinking cap on.

DD: Yes! How did you know that? But you’ll never catch him putting his thinking cap on.

TRAMP: You’ll never catch me putting my thinking cap on.

SHAKESPEARE: There! He can speak for himself.

DD: Who?

SHAKESPEARE (trips over the word “thither”): He. Thither. Yonder he, thither. Thithery he, thither.

DD: He’s Lucky.

SHAKESPEARE: And I’m in.

(Beat)

TRAMP (indicating DD): He’s Shakin’.

SHAKESPEARE: I can see that.

DD: We’ve been sent for Shakey.

SHAKESPEARE: I’m Shakey. You’re shakin’?

DD: You can see I’m Shakin’?

SHAKESPEARE: I didn’t mean to be personal, like, Wac. I meant you look as if you’re shakin’.

DD: Shakin’?

SHAKESPEARE: Shakin.

DD (indicating Butler): Who’s he there?

SHAKESPEARE: Stevens.

DD: He’s Stevens, Shakey?

SHAKESPEARE: Mr Stevens, but I call him Stevens.

DD (to Butler): D’you think I’m shakin’, Stevens?

BUTLER: I’m sorry, sir, but I’m unable to assist in this matter.

DD: And you’re Shakey? I thought you were In, man.

SHAKESPEARE: I’m Shakey. Stevens, aren’t I?

BUTLER: I’m sorry, sir, but I’m unable to assist in this matter.

DD: Hang on, I’m Shakin’ Stevens, aren’t I, Lucky?

SHAKESPEARE: No, I said you’re both lucky.

DD: No, we can’t both be Lucky, Shakey, because only one of us is Lucky. He’s Lucky and I’m Shakin’, Shakey. (looks to Stevens) Shakin’ Stevens, Stevens. (BUTLER is shaking) You shakin’, Stevens?

BUTLER: I’m sorry, sir, but I’m unable to assist in this matter.

DD (back to Shakespeare): See, Shakey?

SHAKESPEARE (draws deep breath): What do you want?

DD: We’re from Miguel.

SHAKESPEARE: Miguel in the sanatorium?

DD: No, not San Miguel, Miguel from Spain.

SHAKESPEARE: You’re servants?

DD: No, he’s Cervant’s, we’re just his helpers.

SHAKESPEARE: And why did he send you?

DD: He moving flats.

SHAKESPEARE: Where?

DD: Madrid, I think.

SHAKESPEARE: And what’s that got to do with me?

DD: He’s done his back in, can you give him a hand, man-o?

SHAKESPEARE: How far’s he moving?

DD: Over a yard.

SHAKESPEARE: And he wants me to go to Madrid for that? How much over a yard?

DD: Fifteen.

SHAKESPEARE: Fifteen what?

DD: Yards.

SHAKESPEARE: How many yards are there he’s moving?

DD: He’s not moving yards, he’s moving flats.

SHAKESPEARE (patiently): What distance is he moving flats?

DD (patiently back): Fifteen yards.

SHAKESPEARE: The flats are fifteen yards away from each other?

DD: No, they’re together.

SHAKESPEARE: In the same place?

DD: Madrid.

(Beat.)

SHAKESPEARE: Just me? There no one else?

DD: A smith, and another guy who’s a bit of a Johnson, actually. But he wants you as well.

SHAKESPEARE: Why doesn’t he get movers?

DD: He’s got movers. We moved. To get here. To ask you to come and help him move flats. He did his back in. They’re very light.

SHAKESPEARE: South facing?

DD: If you turn them that way, yes.

SHAKESPEARE: What do you mean, turn them? Do these flats rotate?

DD (Thinks. Looks at Lucky. Looks at Butler and thinks better of it. Like a technical adviser): You could put wheels on them, I suppose. (Turns to Tramp) Can thi’ rotate?

Lucky rotates.

DD: He’s Lucky, he rotates.

SHAKESPEARE: Yes, I can see that. (In idiot language to Tramp) Hey, you, you rotate flat?

(Lucky stops. Thinks. Lies down on the ground and rotates.)

SHAKESPEARE: I mean Miguel’s flat. You rotate?

(Lucky shakes his head and looks down, realises his face is against the floor, covered in dust, and stands up, holds up a finger, “just a second”, assumes previous face traits and then looks down again.)

DD: He’s down

SHAKESPEARE: He’s really down.

DD: He’s down.

SHAKESPEARE: Down on the ground. (Laughs)

DD: How can you laugh, when you know he’s down? No, he dun’t rotate flats, Señor.

SHAKESPEARE: Well, you can tell Miguel that he has a damned nerve to ask me to twirl his flats thither in yonder Madrid. (Has a realisation) Wait … (counts on his fingers and mutters to himself) … (deliberately, as if concentrating) Thou canst tell Miguel, sirrah, that his nerve, it is dam … nèd for to ask me his flats thither to twirl. (Sotto voce) Eleven. It’s allowed if I’m distraught.

DD: Twelve, but never mind. Si, si, Señor, we will tell him. But he did say to tell you, that, (as if reciting quickly like a court official) if you were to decline this kind and gracious invitation by which you are given a unique and scintillating opportunity to develop your talents, skills and sense of obedience, he challenges you to a duel: jousting sticks at dawn; no lest.

SHAKESPEARE: Done!

DD: No, dawn.

SHAKESPEARE (valiantly enunciated): When is the next boat to Spain?

DD: (echoing the valiant enunciation) Boats to Spain (he looks pointedly at the calendar) are fairly thin … on the … ocean at this year of time. You know, it’s an ill wind that bloweth no Spanish sail.

SHAKESPEARE (To himself): Nice expression, that, must note it. (Writes and speaks under breath) … Spanish sail. (Looks at it, thinks a second and then scrubs it out.)

DD: But! When the windmill doth tilt, we shall have jousting sticks. And what will poor Robin do then, (looking at Butler) batman?

BUTLER: I’m sorry, sir, but I’m unable to assist in this matter.

SHAKESPEARE: Ah, yes, always remain positive.

DD: Lucky’s always pozzo, always goes by the board.

SHAKESPEARE: Ah, yes, the Bard.

TRAMP: The blind always lead the blind when they go by the board.

(He plonks his bowler hat provocatively on his head and starts racing around the stage, Shakespeare and DD trying vainly to catch him, as he recites at breakneck pace the following speech.)

TRAMP: What comes from the sun is in the ordinary visible part of the spectrum that our eyes are sensitive to; what the Earth radiates into space is in the infrared part of the spectrum: longer waves than red, that our eyes are not sensitive to; but it’s as legitimate a form of light as the kind that we’re used to. Now, if you calculate what the temperature of the Earth ought to be, from how much sunlight is being absorbed equalling how much infrared radiation would be radiated to space, you find that the Earth’s temperature by this simple calculation is too low: it’s about thirty centigrade degrees too low. And why is it too low? It’s too low because something was left out of the calculation. What was left out of the calculation? The greenhouse effect. The air between us is transparent (except in Los Angeles and places of that sort) in the ordinary visible part of the spectrum: we can see each other. But, if our eyes were sensitive at, say, fifteen microns in the infrared, we could not see each other: the air would be black between us, and that’s because, in this case, of carbon dioxide. Carbon dioxide is very strongly absorbing at fifteen microns and other wavelengths in the infrared. The sunlight comes in as before but, when the surface tries to radiate to space in the infrared, it is blocked, it is impeded by the absorbing gases, and so the surface temperature has to rise so that there is an equilibrium between what comes in and what goes out. So, this is the greenhouse effect. The greenhouse effect makes life on Earth possible: if there were not a greenhouse effect, the temperature would be thirty centigrade degrees or so colder and that’s well below the freezing point of water everywhere on the planet. The oceans would be solid after a while; a little greenhouse effect is a good thing. The most spectacular case by far is the greenhouse effect of Venus: it’s the nearest planet, it’s a planet of about the same mass, radius, density as the Earth, but it is spectacularly different in several respects, one of which is that the surface temperature is about four hundred and seventy degrees centigrade and that enormous temperature is not due to its being closer to the sun. The reason is a massive greenhouse effect, in which carbon dioxide plays a major role. The atmosphere is almost entirely carbon dioxide and there is ninety times more of it there than here. At the present rate of burning of fossil fuels, the present rate of increase of minor infrared absorbing gases in the Earth’s atmosphere, there will be a several-centigrade-degree temperature increase on the Earth, global average, by the middle to the end of the next century, and that has a variety of consequences, including redistribution of local climates, and, through the melting of glaciers, an increase in global sea level. The idea that we should immediately stop burning fossil fuel has such severe economic consequences that no one of course will take it seriously. Here is a problem which transcends our particular generation: it is an intergenerational problem. It is also a global problem. Nations, to deal with this problem, have to make a change from their traditional concern about themselves and not about the planet and the species: a change from the traditional short-term objectives to longer-term objectives; in problems like this, in the initial stages of global temperature increase, one region of the planet might benefit while another region of the planet suffers, and there has to be a kind-of trading-off of benefits and suffering. And that requires a degree of international amity, which certainly doesn’t exist today. What is essential for this problem is a global consciousness: a view that transcends our exclusive identifications with the generational and political groupings into which, by accident, we have been born. The solution to these problems requires a perspective that embraces the planet and the future, because we are all in this greenhouse together.

(This can go on for a while, so, if you want to insert an Intermission and sell ice cream to up the take, you can do so. Try not to strangle Tramp.)

BUTLER (stentorianly) : Wait, sirs. (All freeze.) (In a plaintive, enquiring tone) Shall I open a window?

SHAKESPEARE: I’m sorry, but I’m unable to assist in this matter.

BUTLER opens the door and they all chase TRAMP out of it. BUTLER assumes the Bob-Cratchit seat and lights a cigar.

BUTLER: Happiness is a cigar. Called Desdemona.

Butler reaches for the glass of red wine. Thinks better of it and puffs at the cigar.

Scene 2

The stage has been cleared. The flats rotated.

Two enormously long jousting sticks—whose holders are never shown—appear stage left and right and proceed towards each other until they cross the entire stage, whereupon there is heard from the wings:

SHAKESPEARE (from the wing on the side marked “Stratford”): Live we how we can, yet die we must. Euuuugh!

CERVANTES (from the wing on the side marked “Madrid”): Merda! Euuuugh!

Jousting sticks withdraw, the ends now covered in blood. Enter right (or left): American FEMALE TOURIST and MALE TOURIST. They wander gawpingly to centre stage, she with a huge guidebook marked “MADRID AND STRATFORD IN ONE DAY”

FEMALE TOURIST (Reading): Hey, honey, ain’t that funny? Shakespeare and Servant-ease both died on the very same day. Ain’t that funny, honey?

MALE TOURIST: Probably drinking wine from the same bottle.

(Enter Butler left (or right) carrying a tray with a napkin and two glasses of wine)

BUTLER: This way, if you please, madam, sir. (Smiles knowingly at the audience) Never let the truth get in the way of a ripping yarn.

MALE TOURIST: That so?

BUTLER: I’m sorry, sir, but I’m unable to assist in this matter.

EXEUNT left (or right)

CURTAIN

SUGGESTED SET DESIGN FOR WAITING FOR THE REMAINS OF THIS OLÉ HOUSE

Scene 1

STAGE R

Rotatable flat showing old-fashioned office things: clock, the calendar, publisher delivery schedules, anything vaguely Shakespearey

STAGE L

Door flat with glazed panel to outside

Scene 2

The flats are rotated, and now show

MADRID (Stage R) STRATFORD (Stage L)

The window in the Stratford flat is now covered with a gaudy poster for the Memorial Theatre.

BUTLER and the TOURISTS approach from different wings but exit the BUTLER’s wing, as circumstances allow or dictate (there must be some directorial freedom).

© 2023 Graham Vincent.