War’s conscientious objectives and its conscientious objectors

From Private Ryan to Tal Mitnick

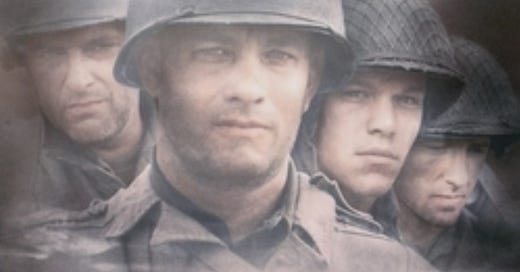

There’s a scene in the 1998 Steven Spielberg film Saving Private Ryan in which Captain Miller (Tom Hanks) and Private Mellish (Adam Goldberg) come into conflict, Mellish challenging Miller’s decision to attack a German gun nest instead of skirting around it to achieve their mission, which is to save Private Ryan:

Mellish: Captain, we can still skip it and accomplish our mission; I mean, this isn’t our mission, is it, right, sir?

Miller: Is that what you want to do, Mellish? We should leave them here so they can ambush the next company that comes along?

Mellish: No, sir, that’s not what I’m saying. I’m simply saying it seems like an unnecessary risk, given our objective. Sir.

Miller: Our objective is to win the war.

James Ryan is played by Matt Damon, who was an unknown when he was cast, but a world hit by the time of the film’s release. But, just like Waiting For Godot, which has little or nothing to do with Godot, Saving Private Ryan in fact has little or nothing to do with Ryan. It has a lot to do with John Miller, and the company he leads in the search for Ryan. Saving Private Ryan was a very successful film, against a number of odds: it was the second-largest grossing film of 1998, contains some astonishingly realistic cinematography techniques (including a pallid, flattened appearance redolent of colour film stock of the 1940s), and was loosely inspired by two similar sole survivor policy actions, one also from World War II and one dating back to the American Civil War (referenced in the film).

There are parts of the film that were cut because they were simply deemed unwatchable by the film’s makers (for instance, the cries of pain from Private Wade (Giovanni Ribisi) in his death throes), and there are in fact parts of the final version that I was able to watch 25 years ago, and which I cannot watch now. Perhaps I’ve seen too much real pain and bloodshed since. Perhaps the intervening quarter century has impressed upon me the need to question what an objective is.

Having initially wanted to make a gung-ho adventure film in order to cast a poor light on wartime public relations exercises, Spielberg changed tack in Saving Private Ryan and ends up asking a lot of profound questions about where our priorities lie. Miller sets out on his venture because he is ordered to, and takes with him a young interpreter (Jeremy Davies), who nervously warns of the masses of enemy in the region they will go to. It is that interpreter who pleads under the rules of combat for the life of Steamboat Willie (Joerg Stadler), a captured German whom they cannot take with them and who is therefore set free. It is that same German soldier who subsequently kills Private Jackson (Barry Pepper) in the Battle for Ramelle, in a plot technique redolent of the death of the Boy in Shakespeare’s Henry V.

If our objective is to win the war, how many micro-objectives are there between where we are now and where the war is won? And, more importantly, once the war is won, is our objective thereby fulfilled? What is the post-war objective?

Miller hints at what his ultimate objective is in the rest of the scene. There comes a point when winning the war is no longer the objective; the objective is getting home to his wife. And he is no longer sure that the same man will return to her as left her to go and fight in Europe, somehow rendering it an objective in vain.

A film must be packaged. It must have a beginning, a middle and an end, and the order in which they come is not all that important. In Saving Private Ryan, the end in fact comes at the beginning. Those who see the movie can be so profoundly affected by the battlefield scenes that one forgets the opening scene: a man visiting the American cemetery at Colleville-sur-Mer (a place I have myself visited on numerous occasions, in the company of American visitors). Who the man is, is unclear until the final reel. Inspired by an event Spielberg himself observed at the cemetery, the man falls to his knees at a cross and starts to weep. It’s a very moving scene and yet its relevance only becomes apparent at the film’s end. It is a film that envelops the viewer and, while a member of an audience may associate with any one of a panoply of characters in any film, the character of James Ryan closely associates with the viewer in this one: this war is being fought by us and for us.

Miller’s company had the objective of finding Ryan and returning him to Iowa. In the course of that, they acquired the objective of taking out the Germans’ machine-gun nest. In the course of that, they come to the realisation that they have the objective of winning the war. So, what? What was the objective of winning the war?

If it was merely to get home, Miller failed. Ryan succeeded, that much we know. The film opens with Ryan mourning Captain Miller in a graveyard. Was that the objective of this war: to make us mourn those who fell at our sides in fighting it? (That was Spielberg’s initial aim with this film, after all.) If so, how often must we fight wars in order to recreate that sentiment of brothers in arms? If war’s objective is to be grateful to old comrades in arms for the sacrifice they made, then why did they make that sacrifice? Is making it home to our families the greatest objective that we can ever formulate for anything we do? And, if the objective of winning the war was to restore peace and justice to the world, did it succeed? Was the objective achieved?

What a film like Saving Private Ryan does is reflect on what sacrifice we are prepared to make, or to have made of us, in achieving a great objective: to create the conditions in which life can thrive more fully, more wholesomely, more freely, more openly, more honestly, more respectfully. It’s more than just getting home, it’s the objective we pursue once we’ve arrived back home.

In the assault on the machine-gun nest, Wade is killed. Despite the misgivings of several members of the company, Miller insists on the assault, on the grounds that the objective must be to win the war. At the end of the scene he weeps, because a man is dead as a result of his fulfilment of an objective that was never one chosen by him, but which he chose nonetheless. Because he followed his conscience. When you follow your conscience, you have no choice in what you do.

Nave Shabtay Levin, Einat Gerlitz and Tal Mitnick are three young Israelis who have spent time in prison for their conscientious objection to serving in the Israeli army. They’re aged between 18 and about 20. Mitnick particularly made headlines because his own refusal to serve in his country’s army came after the attacks of 7 October. They were all vilified in public, prosecuted and marched away to prison, accused of being traitors and collaborators, spat upon and despised, both by society and the prison population.

They have set themselves a higher objective than winning the war. Theirs is an enlightenment whose objective is to win peace, and winning wars is a lot easier than winning peace. If it takes a mountain of strength and chutzpa to don the IDF uniform and carpet-bomb civilians and terrorists alike, without distinction and without remorse, then it takes all the more to refrain from acts of revenge and retribution and to devote oneself to an objective that is far and away beyond the winning of wars. Mrs Lifschitz is our living example of that.

Peace is not an objective for after the war. It is an objective in and of itself. It is achievable even without war, and I’m not even sure it is feasible with war. Some view peace simply as mission creep.

“The man means nothing to me.” Miller gives his life for this man who means nothing to him. This man weeps at Miller’s grave. And, still, do you know what it was all for?

See also:

Honking and waving

France is like England, but without the hedgerows. Or like Belgium with bigger fields. Or like Germany, with fewer cows. Everything in the French countryside looks a bit over-the-hill, tired, knackered, and therefore quaint. There are opulent little houses incongruously perched on street corners, whose attractiveness seems designed to endure for nothing…

A courageous trooper, soldiering for peace

A voiceover of this article is available by clicking above It has taken me 13 months of patient waiting. In the last 13 months, I had not a sign nor a whisper nor so much as a hint in response to a question I posed when the Russo-Ukrainian war broke out. And now, I have the response I sought. The question: Is the united Ukraine that is defending itself a…

Shocking images

I remember seeing Friday the 13th, a horror film, in which a young couple on a bed, making love, are pierced, both in a oner, by the monster wielding a spike. It gruesomely raised from some audience members cries of what I might describe as “exhilarated revulsion.” But all were safe in assuming that what we saw was a trick of cinema. No one died. Still,…

Thank you, Graham. Saving Private Ryan is one of my favorite WW2 films. I watched it for the umpteenth time a month or so ago. It never fails to inspire. Like so many anti-war films, it strengthens our feelings of the uselessness of war. WW2 was the last war we had good cause to fight. Hitler, Germany, and fascism, caused too much pain and suffering to ignore.

Your reference to the conscientious objectors in Israel is well taken