We want freedom and fear slavery

SOCIETY. RAPE. SHAKESPEARE. RACISM. BUSINESS. What is’t to me if your pure maidens fall into the hand of hot and forcing violation?

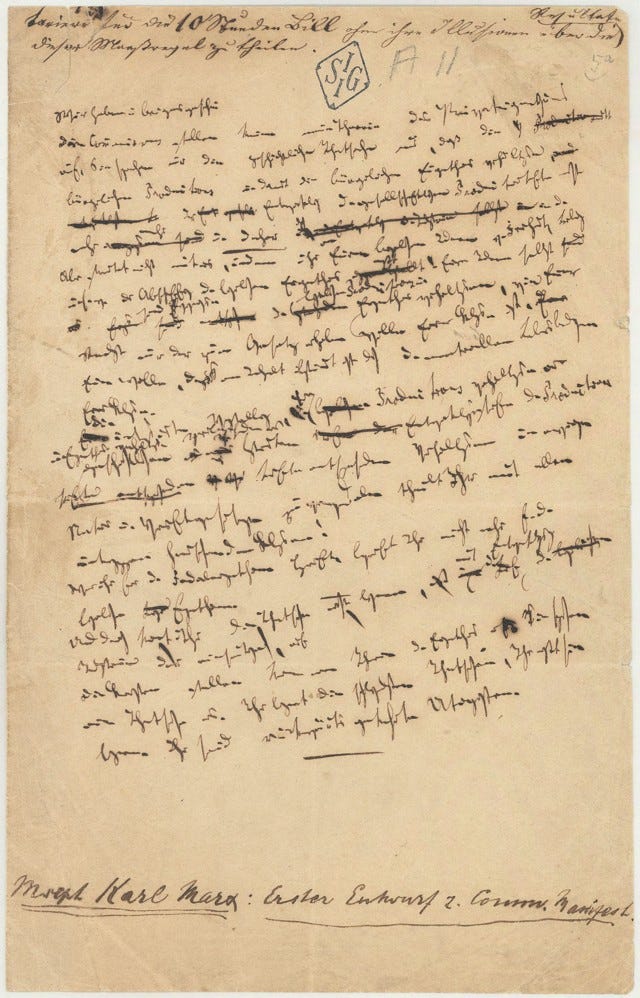

Along his path to London, Karl Marx wrote part of his Communist Manifesto in Brussels, at the sign of the Swan on its Grand’ Place. Brussels did nothing to ameliorate his handwriting.

Not understanding Voltaire: introduction to the art of seeing the obvious

One of Voltaire’s most valiant statements was supposed to be, “I believe that what you say is wrong, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.” Voltaire is frequently misunderstood. He never said it, but if he had, what do you suppose it would’ve meant? Defending to the death someone’s right to voice an opinion that was not in accordance with his own. Would you do that? Why? Why not?

I cannot ask Voltaire why; he has long since departed this world of “thinking man”. But, apocryphal though it is, it’s a statement worthy of reflection, because it comes out of left field. Maybe that’s in fact where the obvious resides.

Defending anyone’s right to hold an opinion, and indeed to defend it to the death makes sense because, to oppose the right to have a contrary view is tantamount to procuring the death of him whose opinion is smothered. Sooner or later, it is so. Those who will not die for free speech acquiesce in a world where no speech is free.

The German poet Heinrich Heine said, a hundred years before it actually happened: Dort, wo man Bücher verbrennt, verbrennt man auch am Ende Menschen. Where they burn books, they ultimately burn people. And, before they burn their books, they stifle their free speech.

By Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-14597 / Georg Pahl / CC-BY-SA 3.0, CC BY-SA 3.0 de, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5415527

They who will not defend free speech acquiesce in the death of free speech. Those who burn books will burn people. They who enlist in a war do not do so for the peace, but in order to die. And anarchists seek freedom and peace, not violence and usurpation. Violence and usurpation are what those who wish to uphold the nation state in fact want.

A friend wrote me: “I recalled that you were into the anarchist school of thought.” I’m sure there are quarters where recollections of this order can get you thrown into a dungeon and, while this man is closer to them than am I, I think we’re both in relative safety, as nor I, still less he, am, are or is planning any act of sedition aimed at the downfall of any established imperial power, regime or nation state. Nonetheless, his recollection is accurate: I am into the anarchist school of thought and, before you turn off and seek out a darkened room and a cool flannel to recover, here are my long-cogitated thoughts of which my anarchism forms my own autodidactic school.

Storage and strife

Mankind has occupied some place on the planet Earth for an estimated 300,000 years, of the vast majority of which there is no record. That there is no record of what we human beings did before paper and cameras were invented is no object to deducing what did or did not, in all likelihood, go on here, until paper and cameras were handily to be found … to hand.

There was probably strife. Chimpanzees and apes quarrel, sometimes violently. I think we did as well, back when, and also now. All the time.

The concept of storage is unique to just a few creatures of which I know, but I’m no naturalist. Squirrels hoard nuts for the winter; bees make honey to survive the winter; bears get fat so as not to fade away. Humans also store things, for later use. But they do something that no other creature does: humans store and manufacture and hew and fell and dig and plant and harvest and all those things on what we call a “commercial” or “industrial” scale. Their purpose is not by any means exclusively for later use; all these activities are done in order to create and serve a market, in which the medium of exchange is classically money.

Our race – homo sapiens, or thinking man – has, during its 300,000 years of development, been far from bereft of that which marks it out as its binomial appellation: thinking. When the activity by which we hope to generate revenue grows in scope beyond our means, we employ others to help us. That, at least, is the theory, but employ to help us is a relative term: it can become exploit as a resource, indeed, a human resource; and it has been known, and is currently also to be found, in the form of slavery. We are the only species on this planet that can conceive of the notions of making, manufacturing or harvesting a quantity greater than that which we need or can reasonably consume on our own, of enslaving other members of our own species to procure the making, manufacturing or harvesting of the commodity in question, and deploying powers of persuasion and legal ingenuity to fabricate or exploit, or deprive others from occupying or monopolising, a market for that which we make, manufacture or harvest.

Drugs and money are synonymous; slaves are not just for Christmas

Money is a synthetic drug invented by us, consumed by us, brandished as temptation by us, embraced by us, consumed in obscene quantities by us, that lies at the root of much death, profiteering and manipulation of others, which knows only universal approbation (bar outliers – outliers are discounted for the general thrust of this paper). Money never did anyone any harm. That’s as callous and manifestly wrong a statement as one can conjure.

I would warrant, but have nothing with which to back the warrant, that crystallised methamphetamine hydrochloride, a scourge for which there is no known cure, an eroder of society and of relationships, the subject of unconscionable summary punishment – long-term prison in some countries, death in others – that is far less insidious than any Oath Keeper might “otherwise” procure by virtue of their planning and machination, and that to a power of ten, is less destructive for the human species, and all other species that share this, our planet, with us or, indeed, the planet itself than is money.

Drug users may well raise a finger of protest: that meth has certain benefits; and, equally would I warrant, that any voice given to him or her may well be met with scepticism, a tendency that all should take counsel to moderate as far as possible: one never knows what information may be lurking in the least expected of quarters. Fingers of protest that voiced the view that money proffers, it too, certain benefits would no doubt find nods of approval around our courtroom of public opinion, and therein, i.e. in these two views – one a “bad one” and one a “good one” – lies a fundamental problem with advocating methods, methodologies, views and systems that might be as equally valid as an existing equivalent, functioning system, but get rejected because the proponents of the first have, whether by accident or design, built a bias into that system which rejects as of nature any challenger to it.

Perhaps I can offer a real example known to have occurred, albeit the roots thereof are unknown to me in terms of “inherent bias”: it can be safely posited that the Ancient Romans had the knowledge and technical know-how, had they so wished, long before James Watt ever observed a kettle on a range, to develop the steam engine. It’s a notion that forms the subject of a play: The Brass Butterfly, by William Golding, and it’s a funny play, but it’s not entirely fictional.

Our world would look very different today, 2023, had they done so. The main reason why they did not do so is feasibly simple to find: as a labour-saving device, steam engines vaunt themselves most persuasively to those whose labour would be saved by them. Ancient Greek mathematicians had fairly accurately estimated that the human frame could not possibly withstand the pressures inflicted upon it if it travelled at a speed in excess of 21 m.p.h. Both Ancient Greeks and Romans knew the speed of 21 m.p.h.: it is roughly the speed of a galloping horse and, until Richard Trevithick exhibited his device in London in 1804, 21 m.p.h. was the fastest speed that anyone would ever achieve on Earth and survive the experience. Till then. The device that Richard Trevithick exhibited was: a steam locomotive.

The calculation of the maximum human speed was accurate: take a motor car to 21 m.p.h. and then lean out of the window in a forward facing attitude, and you will note, as does every kid, but few dogs, that breathing becomes a challenge. Speed brings asphyxiation, and for Romans and Greeks, that was that. The concept of taking your atmosphere with you in an enclosed space was a simple step, but one that was one too far for them. They never explored the idea because of a fundamental objection to steam power at all: who needs steam engines when you have all the slaves you want at your every command to save you enough labour to spend all day in the bath? Those whose labour the steam engine would have saved were in no position to develop a steam engine.

I cannot offer any detailed submission beyond surmising that the Ancient Romans had a developed system and market for procuring, buying, selling, utilising and exploiting slaves; and these systems and markets will undoubtedly have all had their own operators, possibly licences, permits and structures to ensure their smooth efficiency. Introducing steam engines and mechanical devices to perform the same tasks as were performed by slaves would have entailed dismantling these systems and structures, and those who worked in them and profited from them would no doubt have had objections to any such proposal.

This I can assume from the simple fact that, when it was proposed abolishing slavery in the West Indies in the early 19th century, the objections from those who owned and exploited slaves and profited from slavery needed, in order to see justice in the abolition movement, to be paid to deny themselves their capital goods. There is no reason to believe that the considerations that obtained in Ancient Rome would have in any way differed from those that obtained in the British Empire in 1833 or in the United States of America in 1863.

What we want; and what we fear

The drug “money” that mankind devised as a means of exchange unquestionably offers a huge variety of benefits in terms of its simplicity, ease and negotiability; but it is still nonetheless a drug, whose addictive qualities at least equal if not outstrip the addictive characteristics of many a class-A narcotic.

If cocaine or meth, or whatever, is a chosen poison such that it enslaves through addiction, this has nefarious effects for the addict him or herself, and for his or her immediate family and those in his or her immediate entourage. The trade in the drug and its transportation pose two major headaches for law enforcement agencies like the police; but the circles within which such trade, exchange, dealing and use and exploitation are accepted in every sense of that word as normal, as conscionable and as unobjectionable, thus constituting the business of good business are minute compared to those within which the drug money receives widespread applause, praise, laudatory vocation, slaps on the back and approval; in short, money is seen as rightly and properly forming a route to the one thing that all men and women desire more than anything else on Earth: and that is freedom. (Coincidentally, the exact same purpose for which the addict consumes narcotics.)

Already mentioned above is the single consummate thing that men and women fear most on Earth: and that is enslavement. Our existence on Earth is optimistically viewed as facilitating, from birth to death (and even thereafter) and mostly between these two extremes, our ascent, be it gradual or sudden, away from what we fear most and towards that which we want most, to money and freedom, away from penury and enslavement. Our lives then comprise a trade-off: between the amount of enslavement that we are prepared to accept into them in exchange for selling our labour in return for money value, which we conceive of as being our route out of enslavement and into freedom: pity the workaholic who devotes their life to work, and thereby achieves no freedom but enslaves themselves entirely. The more one can procure money for less work, the freer one becomes. And he who can procure most money for least work (e.g. a private income) is freest of all.

Marriage is bunkum

As for warfare: history is divided into periods of peacetime and periods of wartime. History is, as Henry Ford once famously said, bunkum. Peacetime is simply the time between wars when folk, more accurately most folk, lay down their arms, but, during this time, warfare continues: it is simply conducted under the guise of international commerce and trade.

Lawyers are adept at clarifying, explaining and laying bare the structures that govern how we live. But the one structure that they are most adept at presenting to the gullible member of the general public is the whole business on which law, certainly in the civil sphere, is even conceived of, and that is the so-called meeting of the minds. Let us take for our example what must surely be regarded as the most equanimous and fair meeting of the minds that exists anywhere: the contract of marriage.

A man stands before God, or a registry clerk, and takes a woman (classically, or such other version of the human race as fits his wont), for his, let’s call it lawfully wedded wife, to have and to hold from that day forward, in sickness and in health, for better or for worse, until death doth them part. It is, I think, so self-evident as to hardly need pointing out that a contract of such key fundamental putative importance to society (although it contributes, nowadays, little to that society) can only be entered into as a meeting of the minds: there must, so to speak, exist consent on all sides. But I wonder how freely and willingly the consent of each of the parties is given to the union.

What we do know is that, in some countries, the union of marriage is sooner or later viewed as a mistake by one or another or both of the parties during the contemplated duration of the union that is entered into (i.e. the joint lifetimes of the two parties), since a third of all marriages are dissolved. They really ought to amend the basis on which marriage is entered into for only in realistic cases, or at least not in all, does marriage endure until death and otherwise it’s not death that parts the partners.

If you venture into the commercial world, the meeting of minds becomes a rare feature indeed. Little doubt, you’ll be party to the multitude of contracts that govern our existence in the modern world on the Internet and so you will know that, in one respect only, is your consent sought repeatedly to the point of exasperation: that of website cookies. In most, if not all, other respects, your consent is requested, sometimes even politely, but it’s never negotiated. Either you give it and receive the service that you seek or you refuse it, upon which the service is refused; and it is my contention that “Take it or leave it” is no “Meeting of the minds”; instead, it is acquiescence in the face of duress. To see this as manifesting a will on the part of the supplier to meet with your mind makes a mockery of what is ultimately the very basis of the law of contract.

If marriage is so easily dissolved, why do we insist on stepping before God in order to seal our union? Thomas More went to the block because he refused to swear an oath, a simple utterance of words, before God and yet we reduce the sanctity of marriage to nothing more than wishful thinking, as if we were gambling with our lives’ futures. Those who opt for a marriage before God should exclude the possibility of divorce, eschew pre-nups and commit based on a meeting of the minds. Yet, under some laws, they don’t even have that option. The simple fact is this: people like parties; and a wedding is generally a pretty good one.

We devise rituals that avoid us needing to examine in depth what it is that we do; and then introduce exceptions that make of the ritual a mockery, and spare not a thought for what we do. And we, nota bene, are thinking man.

This is one small example within a panoply of examples that criss-cross our modern lives. It is admittedly reasonable to rely on a wheel being round without having to reinvent it. But some wheels are truly square, and pass muster without question.

Warfare will be the death of us

Warfare is an occupation that is instituted by owners – states, or overlords – executed under the direction of generals and engaged in by troops. The troops do as they are bid on the understanding that, if they win, they will be rewarded. Rewards are distributed according to spoils. If the spoils are many, the winnings are many. No spoils, few winnings. To this comes the acute possibility of not surviving the battle.

So, rape is a standard clause in any agreement by which troops serve a general in wartime. They may, after all, not see the battle out and they must have some kind of incentive to attract them to such a dangerous activity. That’s why rape is in as standard. It is in Ukraine, it is in the DRC and in Ethiopia, and it was at Harfleur in 1415. You don’t believe me? In the footnote is the entire scene describing – I believe entirely accurately – the nature of Henry’s conquest of Harfleur and its inhabitants.[1] That’s how objectionable war is. Honourable warfare assumes the survival of all parties engaging in it, and one that is worth the having, at that. Honour comes cheaply when survival is assured. And, like advertising, it sells – in such a case, it sells going to war. Generals are less likely, albeit not immune, to be killed in warfare, and their rewards are great. Duchies, earldoms, ships, great houses and jewels. These are bestowed by the owners who gain control of territories and peoples, and who give grateful thanks for the acquisitions by rewarding the generals. The generals will also reward their surviving troops, but they may end up with a few good women, nay men sometimes, and little else. That is warfare.

Commerce is no different, except there is less shooting. But there is not no shooting. The troops are instead shop-floor workers or labourers or whatever they are, and they do the bidding of the generals, who are now company directors, who, upstream, follow the instructions of their owners (stockholders), who urge them on to the next victory, to conquer new territories – they call it market share.

The rewards are analogous to those on the battlefield (medals, or fountain pens): commerce is frequently alluded to as a being tantamount to a battlefield, and that is untrue. It is in no manner tantamount to being a battlefield; it simply is one, not without good reason. The instigator of a war, a state or powerful individual, is paralleled in commerce by shareholders. The interests of shareholders are poorly served by a company that acquiesces in the better right or even the worthy, nay legal, right of the competition. They fight the competition in court, on the market place, in the war for talent, and use tricks legal and unlawful to manipulate and contort market forces to their best advantage, never forgetting the ultimate legal challenge: get the law made the way you like it, by greasing the palms of those who make them.

Companies weigh up the benefit of leaving the Earth untouched, just as a general will admire the beauty of a landscape, and then engage in destroying it by digging up oil or coal or iron ore and reducing the prettiest of meadows to an Armageddon landscape, much as tanks do. Tank battalions apologise for making mud, but explain there is no other way to drive a tank across a meadow. And companies make faux apologies for reducing the Arctic shelf to a wasteland, in their quest for natural gas.

For 299,000 years, mankind husbanded its world in a manner that, for all I know, but could have involved acts of death, murder, warfare, battles, armies; I don’t know. And the disadvantage of the time before recorded time is that we have no record of what went on, so we must guess. However, recorded time offers the great advantage that we have records of what we and our forebears have done: we could view the consequences that these acts have had on the Earth, its atmosphere, its subsoil and its people. We can look at the cemeteries and we can see the slag heaps, the waste piles, the mountains of unwanted goods, the smog, the gases prompted by our cars and our trains and our fireplaces; and we need to turn our minds to questions of whether the negative impact of our existence on the Earth, at a period of little more than 250 years, couldn’t in any way have been abated or avoided with thinking people in charge.

Well, it could have been; we think as a race, and we complement our thinking by thinking about the future; then do nothing about it and credit ourselves with having thought about all contingencies, which is a fraud we practise upon ourselves, but at least it’s not done at the point of a gun.

No matter how often the lesson is repeated, we don’t learn

Our mistakes stem from man’s ingenuity, which is ascribed as being his ability to apply his mind to solving problems. These problems include the consumption of need and desire and the means to fulfil those needs and those desires. High on the list of priorities down which we may perchance encounter the aspect of ruminating about the Romans and their consideration of steam engines as a possible alternative to slavery, is the aspect of living that we call comfort. Comfort is an aspect of living that is visibly sought by other species as well. Indeed, the climate emergency that we are currently living through sees creatures migrating or moving in what is to be seen as a clear pattern towards areas that have a temperature or climate that they’re suited to. It may be a colder climate than what they’re being asked to put up with now and it may be a warmer one but we see the dog cross the living room and go and settle in the patch of carpet that the sun is warming by shining through a window pane and we ourselves shift in our seats at our writing desks in order to relieve a stiffness that has set in, because our seat is too high or too low or too much to the left or presents something that makes us raise in our minds an objection, that in truth was no objection: just for comfort.

I am not anti-comfort: whether I sit on my chair in one attitude or in another really has not got any consequences other than for me and the chair; but there are things subjected to the application of ingenuity from mankind that seek a comfort that is singular, exclusive; that is superfluous to standards of comfort, laid down by whomever, as a need. Money brings the freedom; but it brings in comfort as well and slavery is a concept that’s rarely associated with comfort, quite the contrary

How low do we descend if we come to a realisation of what we as a race have done to our home over the smallest span of time? It’s as though we had smashed our way into a hallowed ancient country home and taken some swag bag for its contents in a rabid desire to acquire everything we can grab, just to turn it to account and sell it to all those like us, who we know harbour an abhorrent acquisitional desire that’s every bit at the level of our own, as we whack a rival over the head for trying to nab the bath taps before we can get upstairs: what’s wrong is a realisation of our failure, abject and total in brokering lasting peace on our globe over a span of more than a thousand years: if that’s our experiment, when do we admit we tanked? If, on the contrary, we were capable of applying thinking minds to thinking, and to thinking about people, to the shambles that we have wrought, is it conceivable that we could reboot our existence but send it on a path that mitigated the very worst of our excesses?

One last chance? Fat chance.

There are, to my mind, two ways to do this, and neither of them is especially attractive. There are two domains within which we would have to consider how to proceed, and these are the two domains spoken of, war and trade. In the field of warfare: it must be abolished. That’s a challenge that represents no mean achievement if it’s achieved.

The formula is as simple as it is simplistic, and as incommodious as the tablets of stone that Moses himself brought down at God’s command from Mount Sinai: fix the borders of every last nation in the world, and be done with it. And if anyone is unable to agree the borders thus fixed and if they raise military power to enforce what they consider to be their right to land occupied by another power, then all those who do in fact agree must unite in sure strength to bring the miscreant to heel. No negotiating, no compromises, no settlements, just do it. We have put millions and millions of members of our human race through the mills of greed, hatred and the machinations of despots and democrats alike, and it must stop.

What’s more, in the thousand years or so of recorded history and, to boot, not at any time prior thereto, there has been no period, none whatsoever, during which warfare or military conflict of some kind was entirely absent from our globe. In short, we are pitifully lacking in our ability to practise our professed mastery of the world: all we do is squabble. How much more practice do we need?

As far as commerce is concerned, far from being governed by a putative meeting of the minds, our worlds of commerce are governed fundamentally by man’s greed and covetousness: his desire to acquire more than he needs and to manufacture both things to need and the concept of need as a putative justification for his avarice.

Greed means three very different things in three very different contexts, which differ but in their degree of repugnance. First is the concept as applied by First Nation peoples, typically in North America or Australia. They live by a simple mantra: to take from the land what they need, and nothing more; and to return to the land what they are able to, and nothing less. In this, argument arises simply based on one man professing a greater need than another. Need is not something that is controlled and measured; it’s felt, and every one of us knows what we need and what we don’t; we eternally measure ourselves against a standard that we ourselves have designed, and feign surprise when we fit it: we designed it.

In Molière’s play The Miser, the central character, Harpagon, amuses the other characters and the audience with his ridiculous means for preserving his fortune. We don’t know in actual fact how his fortune has been amassed, but he goes to great comic lengths to preserve it. Yet, Molière does paint his character as having one virtue, if no other: at no point during his play does Molière contrive to have Harpagon covet property, money or any possession that is rightfully the property of another person – he’s no thief. His concerns are limited simply to preserving his own fortune, but don’t extend to acquiring the fortunes of others.

The third, and by far the worst, degree of greed is that which is manifested by the banking system and the stock market. They turn not a hair at the prospect of bankrupting those who do business with them, in the interests of acquiring their property, sequestered as legally theirs by virtue of debt or some contractual meeting of the minds: the law’s guarantee of protection for lenders has made devices that procure insolvency and the glut of the windfall. If ever a ploughshare was turned into a sword.

These systems are born of the notion of the nation state, without which much, I’m sure, would never have come into being of what we regard as technological progress, medical research, organisation, good government, academic achievement, schooling, a path of life that’s laid out before us like some pre-destiny that all you’re going to do is tread upon, filling in the details as you go. Simplicity is assuredly the hallmark of modern living, compared to inventing wheels, that is. The nation state levies taxes and queries with its demands; it declares our freedoms, which we must then delimit: a necessary adjunct to freedom, for no freedom is in truth liberty until it be constrained by the bounds of an obligation, at best one imposed by the right-holder’s very own conscience. But, to not labour for freedom is to will a myth: true freedom can only be attained in a state that is no nation state; and, to achieve that, we must abolish the nation state and with it the boundaries that demarcate one nation state from another, if only to be rid of the prime reason for which man has ever gone to war. In short, our freedom ceased when our serfdom was abolished and industrialisation vaunted as our path to self-betterment; as those who instituted factories bound us like slaves to a freedom that is but intangible, and an enslavement that is only too tangible.

Pre-industrialisation, poverty and menial existence went hand in hand with a purity of air, clear, running streams and a self-sufficiency that ensured our lives, all of our lives, were nasty, brutal and short. Aye, but they were ours, not lived by proxy in times long before our here-and-now period of industrial development; if you like, I advocate an existence that existed 299,500 years ago; and whether it worked or not, whether it was comfortable or not, whether there was misery or happiness in abundance, I can see but one thing I do know about that 299,500-year period. And that was this: that if it was a failure in achieving universal human happiness, it failed to no greater extent than recorded time has shown with its raft of warfare as having failed likewise. And, as the age of Bentham’s greatest happiness of the greatest number recedes to assume its more cynical shape of “least misery of the least number”, I feel a little like Beckett’s Pozzo and muse that, if misery is to be a universal inevitability, then it’s no less so that happiness is to be regarded as the same. All that changes is the crossing-point at which the miserable, by some standard or another, become happy.

To this extent am I an idealist and, you’ll be happy to know, at the same time realistic enough to know that happiness for all in a state of being 3,000 centuries ago entices no more than the homespun worsted of that age. If it’s unwilled, it’s unachievable. It’s an idea whose time has long since passed.

We, we are the human race, the people, who serve the god Greed and dress it as altruism: we posses, master and command the ability to store for the future and to sell to those around us the surplus of what we make, manufacture and harvest. Fear not, though I suspect no mighty dread fills your minds: anarchy lurks not in the wings of this theatre of war.

We need a United Nations that unites for all nations. It’s too much to ask.

We need justice, for the asking: but it is wanting. We want it.

And, we want trade to be a meeting of minds and not a powerplay. It’s what the law says it is. So, let it be what the label says.

Otherwise, we get anarchy. And we wouldn’t want that; not for all the world.

[1] King Henry V by William Shakespeare: Act III, scene 3.

King Henry: How yet resolves the governor of the town?

This is the latest parle we will admit;

Therefore to our best mercy give yourselves,

Or like to men proud of destruction,

Defy us to our worst; for as I am a soldier,

A name that in my thoughts becomes me best,

If I begin the batt’ry once again,

I will not leave the half-achieved Harfleur

Till in her ashes she lies buried.

The gates of mercy shall be all shut up,

And the flesh’d soldier, rough and hard of heart,

In liberty of bloody hand, shall range,

With conscience wide as hell, mowing like grass

Your fresh fair virgins and your flow’ring infants.

What is it then to me, if impious War,

Arrayed in flames like to the prince of fiends,

Do with his smirch’d complexion all fell feats

Enlink’d to waste and desolation?

What is’t to me, when you yourselves are cause,

If your pure maidens fall into the hand

Of hot and forcing violation?

What rein can hold licentious wickedness

When down the hill he holds his fierce career?

We may as bootless spend our vain command

Upon th’ enraged soldiers in their spoil,

As send precepts to the leviathan

To come ashore. Therefore, you men of Harfleur,

Take pity of your town and of your people,

Whiles yet my soldiers are in my command,

Whiles yet the cool and temperate wind of grace

O’erblows the filthy and contagious clouds

Of headly murder, spoil, and villainy.

If not—why, in a moment look to see

The blind and bloody soldier with foul hand

Defile the locks of your shrill-shrieking daughters;

Your fathers taken by the silver beards,

And their most reverend heads dash’d to the walls;

Your naked infants spitted upon pikes,

Whiles the mad mothers with their howls confus’d

Do break the clouds, as did the wives of Jewry

At Herod’s bloody-hunting slaughter-men.

What say you? Will you yield, and this avoid?

Or guilty in defense, be thus destroy’d?

Governor of Harfleur: Our expectation hath this day an end.

The Dauphin, whom of succors we entreated,

Returns us that his powers are yet not ready

To raise so great a siege. Therefore, great King,

We yield our town and lives to thy soft mercy.

Enter our gates, dispose of us and ours,

For we no longer are defensible.

King Henry: Open your gates. Come, uncle Exeter,

Go you and enter Harfleur; there remain,

And fortify it strongly ‘gainst the French.

Use mercy to them all for us, dear uncle.

The winter coming on, and sickness growing

Upon our soldiers, we will retire to Callice.

Tonight in Harfleur will we be your guest;

Tomorrow for the march are we address’d.

I think you’d like this book a lot: https://www.twelvebooks.com/titles/ajit-varki/denial/9781455511914/