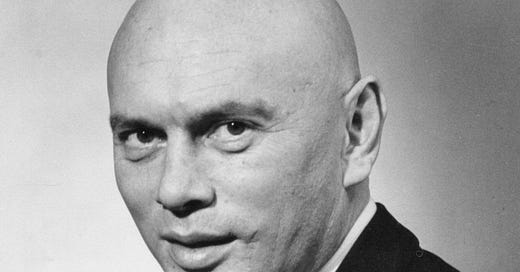

Yul Brynner: The Double Man.

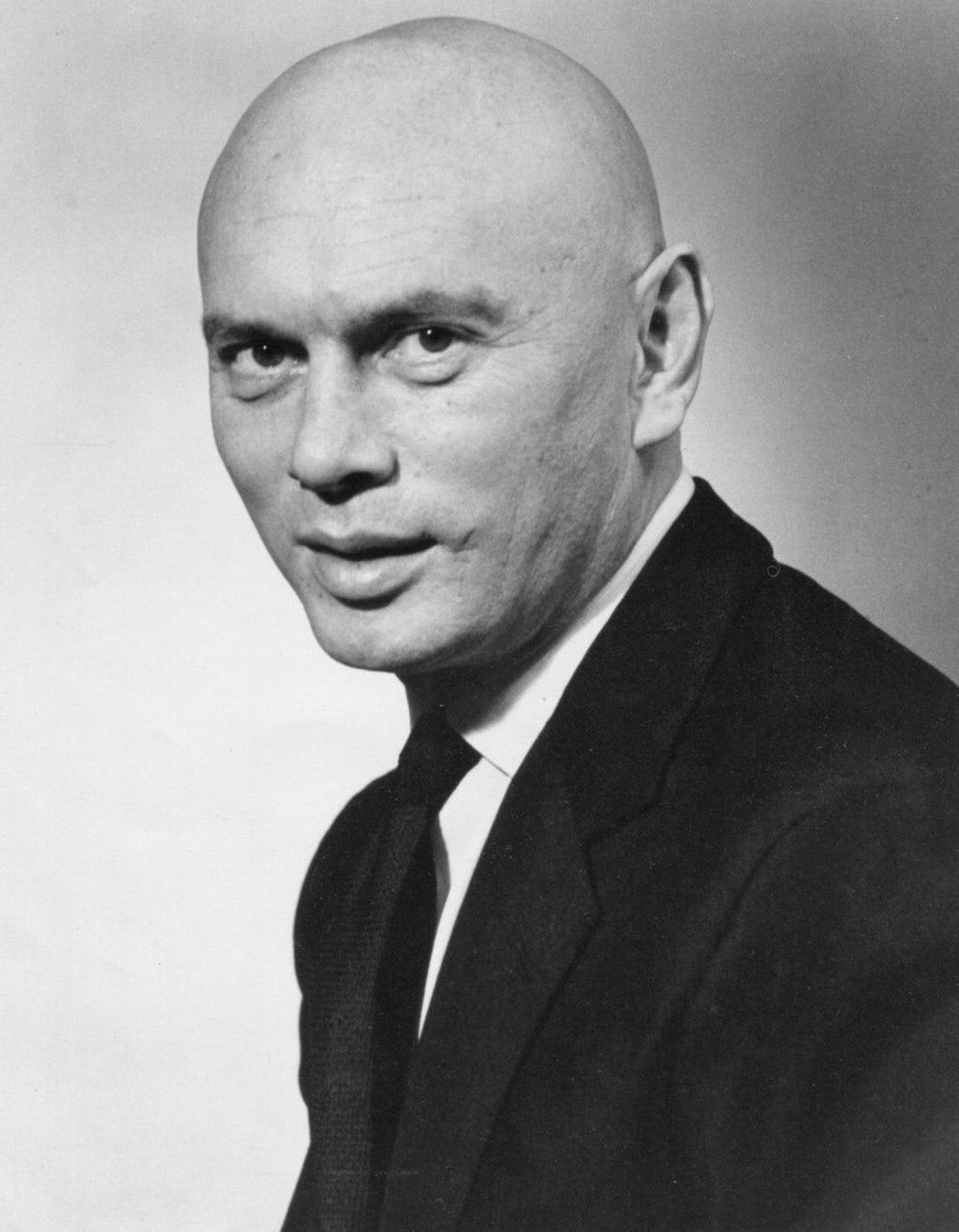

Yul Brynner: The Double Man, again.

The Double Man is a 1967 spy thriller starring Yul Brynner. One of the lesser-known of Brynner’s lesser-known films, it opens at an alpine café, where Mr Brynner approaches Britt Ekland, who’s sitting alone at another table. He asks if he may join her, in English, to which she replies, in French, that she doesn’t speak English. He repeats the request word for word in French, to which she answers, word for word, in English, that she doesn’t speak French. Had Brynner pondered for a second the multiplicity of high-profile personalities that Miss Ekland had partnered up with in what can only be called a whirlwind life, he might have concluded that that was that with this totally cool put-down (perhaps noting it to use some day himself, maybe in some crowded lift). But, alas, he is otherwise preoccupied with the small matter of who murdered his ski-fanatic son. The put-down belies a truth about all those who speak two or more languages: we’re all “double people.”

There is a put-down available to the polyglot that is equally offensive to that in Brynner’s movie, albeit not quite so cool. It’s doing the opposite to Miss Ekland: no matter how proficiently you speak their language, some people will always cannily discern your own (a lapel badge, perchance, your brand of sneakers, or a shibboleth, something like Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch, which can really sort the wheat from the chaff, especially if you can reply, “Iawn, ars bach smart, dim ond aros nes i mi gael chi ar dafodieithoedd Mongolia Fewnol.”

So, what language do you speak?

In diplomacy, they used to speak French. Now, they speak English. In a diplomatic incident (like an all-out invasion - they do still occur), they speak their own, and try hard to mispronounce the other side’s name. Like saying Nazi as if it was Indonesian rice. Or Herr Hitler as if he was the latest bouffant.

A salesman speaks the language of his customer. If he wants the customer.

Your foreign language lover or partner speaks the first language they spoke when meeting you. If they change to your language, you will think you have a new lover or partner and will be so irritated that you’ll probably need to ditch them pretty soon afterwards. One-night stands know when to leave in any language.

At weddings and funerals, everyone speaks platitudes. Feel free to say yours in your own language: then, the sentiment comes over more sincerely, and that’s what counts with a platitude.

On a large company’s telephone “menu choice” answering service, you speak the last language they offer (and I swear they all go through to the same operator anyway). You will laboriously key in your client reference, address, sex, date of birth and national insurance number and, when your call is answered, they will claim they haven’t a clue why you’ve called and ask you for your client reference, address, sex, date of birth and national insurance number, and then tell you that you need to call their Geneva office.

The town hall speaks the language of the town hall. Or another language. But the same person never speaks both.

No Paris waiter speaks English, even if they do. They probably think the fact you know they do ups the tips they get. It probably does up theirs, but no one else’s. They don’t like being called “Garçon!”, though. If you want to try it, pick a café you’ve already decided to leave.

Sacha Distel spoke pitiful English and nurtured his lack of proficiency, claiming his accent brought him enormous record sales. If he but knew, the women of England didn’t have their beady eyes fixed on his epiglottis.

The Vatican speak Latin. Apparently it’s easier than learning Esperanto. The Swiss think so too.

The Spanish speak Spanish but so WISH they could speak your language. About the same proportion as there are people anywhere who’ve always wanted to go to Scotland.

The Italians speak Italian and, when they speak to you, they will double the speed of delivery. At least, it seems that way.

In San Marino, they speak Italian, drive Italian cars, eat Italian food and gesticulate a lot. But don’t ever call them Italians.

The Dutch, when spoken to in Dutch, will reply in English. Even if you’re Norwegian. And then they’ll correct yours, while laughing heartily.

The Swedes speak a language that, if you know German, you are fluent in if you see it written and say exactly what it looks like. Then they’ll switch to English. Especially if you’re Norwegian.

If you’re the only English speaker in a room of 50 Belgians, they’ll all speak English. Even to each other. It’s a humbling experience. But no one in Belgium knows what “eventually” means, although I have no ready tips on how you would work that tactical knowledge to your advantage.

The British speak English except to non-English speakers, who they bawl at in English, occasionally missing out verb tenses and prepositions in a bid to aid understandability, and amply filling in the gaps thus created with putative sign language. (It’s hard to shout “for”; except on a golf course.)

It’s the language they’re spoken to in (try bawling that little couplet) that Belgians otherwise speak, unless it’s the other language. I know there are technically two, but there’s only one other language. If they reply in what they perceive to be your language, this means nothing about their abilities in that language. It’s just a subtle – well, not very subtle – intimation of the fact they are one point up on you in the parlour guessing game they’re playing with you.

Africans speak French or English with an accent that the French and British find sooo charming. And which Africans find bloody normal.

Americans think the British speak English with an accent that is sooo charming too. Which the British are putting on for them. “Having a bang”, nota bene, does not, in America, mean “to be at the sharp end of an electric shock” and, whatever you do, never volunteer to knock the girls up first thing in the morning. Call girls, instead.

Cross-channel ferries speak an English that, in targeting residents of Kent and Essex who are accustomed to what is quaintly known as Estuary English and whose sartorial taste comprises garments emblazoned with three stripes, avoids, as far as humanly possible, using any words that a sailor might have a cat in hell’s chance of actually knowing the meaning of. Goff.

Belgian trains are unilingual, depending which bit of rail they’re on. It makes the line from Louvain to Liège linguistically challenging for onboard staff, with announcements changing about every 3.2 kilometres. In Brussels, however, they’re bilingual. In no particular order. But airport trains assume travellers haven’t a ruddy clue and add in a spot of English, just for fun (using the offensive “track” for “platform”, and then constantly reminding people to stay off the track). They don’t much care whether you know where ’s Gravenbrakel or Borgworm are (no, it’s not an intestinal affliction), but heaven forbid you should miss Brussels bloody Airport.

Eurostar trains speak French. Followed by Dutch. Followed by German. Followed by English. In that order. For every last thing they say. Including the sandwich fillings. It’s at the point where you are looking for a shoe to throw at the intercom system that an announcement will thankfully stop. I think it’s to make the British feel inferior (which isn’t hard these days, I’ll admit). To maintain language equality at all costs, no announcement is made at all, in any language, when the train catches fire 400 feet below the tumultuous English Channel.

And, finally:

Chinese restaurants outside China and employing speakers of Mandarin or Cantonese will use this lingua franca among themselves and feign an inability to understand anything a diner says that includes an article, definite or indefinite. It can be handy to learn Chinese numbers, at the very least, and things like “Have you by any chance lost a weather balloon?” However, they’ll commonly identify diners not by table numbers but by such as “The fat git with no taste in ties” or “The couple who think they’re Lord and Lady Muck” or “The idiot who can’t park a bicycle.” Diners whose linguistic abilities enable them to understand these oblique references can ensure an extra round of liqueurs and fortune cookies by reserving their display of proficiency to the “How was your meal?” stage of the proceedings, when they can give marks out of 5 from the fat git, his lord- and her ladyships and the bad bike-parker. “Were you wanting a tip?”