Will the Earth move for us?

SCIENCE. CARTOGRAPHY. Chancing upon a news report reminds me of 1982

Junior geography lessons at school were spent, in part, poring over Ordnance Survey maps. The Royal Ordnance was originally the government department responsible for manufacturing small arms, explosives and the like for the military, and, after the Scots rebelled in 1745, the Ordnance Survey was set up under the Royal Ordnance Factories’ aegis to make maps of Scotland to keep tabs on the pesky revolting Highlanders. Ultimately, it was the Ordnance Survey who, with their scouting expertise, were given the job of mapping out the entire British Isles, to scales ranging from large to small. In school, it was the scale of 1:63,360 that we pored over, or one inch to one mile.

Aside from learning symbols for churches, with towers or spires or without either, and battlefields, and trunk roads and the like, and plotting gradient charts using contour lines, our attention was drawn to a legend at the side of the maps that told the reader where “grid north” was to be found (for which convenient grid lines were drawn on the map at one-inch intervals, which we used to plot grid locations) and where, in actual fact, “magnetic north” was to be found on the date of the map’s publication. There would also be a note indicating the rate at which the difference between the two was calculated to increase or decrease, so that, by knowing the date on which the map was used (to the year was enough), anyone using a compass and the map for direction purposes could make the necessary corrections from their compass reading to know which direction they were actually heading in by reference to the map in front of them. Those were the days when map-reading was fun, and not just a case of following a GPS indicator.

(Above) From my own collection, this scan is taken from the Ordnance Survey for Scotland map for Dingwall, its 1866-75 survey, revised 1908-09 and published 1912, printed 1913. Grid north points here to the left (between the outlined crosses), with the magnetic north variation shown as being 19°28’ (nineteen degrees and twenty-eight minutes) to the west in 1913, decreasing by 6’ (six minutes) per annum (albeit not at a constant rate). A traveller in 1913 therefore knew that their grid north direction as per the map lay roughly 19° 28’ to the east of the direction indicated by their compass. In 1914, grid north was only about 19° 22’ eastward, and so on.

Even over the entire length of Great Britain, the difference in the size of grid squares from Land’s End to John O’Groats (in view of the Earth’s curvature) would be minimal, and so the curvature of the planet is ignored for gridline purposes (grid north being deemed to remain constant despite the convergence at the poles, and latitudinal lines likewise remaining constant values); hence, the map takes the time-honoured Mercator projection as its basis (on which longitudinal grid lines never converge).

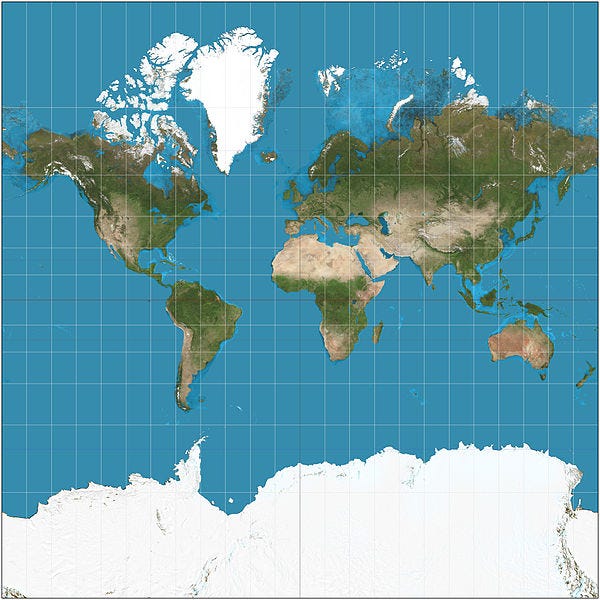

(Below) A map of the world on Mercator’s projection, on which the longitudinal gridlines do not converge at the poles, as they would in reality. Consequently, Greenland is shown as apparently being the size of Africa, and Antarctica appears as a humungous mass at the foot of the map. True scale is represented only on the thicker line that passes latitudinally through the northern portion of South America, equatorial Africa and Indonesia. Everywhere else is to some extent distorted.

In my 20s, I worked for some 12 years, all told, in the tourist industry and the companies I worked for engaged the services of charter coaches, with driver, of course. As tour director and driver, we were the team that ensured comfort and convenience for our passengers, and we often socialised together in the hotel bar or on an odd evening’s excursion or optional. The drivers were always characters and entertaining and, for the most part, enjoyed the odd bit of chit-chat with our travelling guests.

One driver, whose name now escapes me, but who hailed from one of the provinces of Holland in the Netherlands, regaled me with a tale one day that made me stare in disbelief and which I couldn’t but dismiss as poppycock, or, as they say in Dutch, papkak. He avowed to me that he held firm to a belief in a cataclysmic event that was foretold to take place in the, then, distant future. The year in which he told me of the prediction was approximately 1982.

He and, he assured me, a good many others, predicted that the event would result in vast destruction and a huge loss of life, albeit not the entire elimination of our human species. It would set the world back to where it might have been several tens of thousands of years ago in terms of progress or development. It was a doomsday scenario, absent the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. He told me when it would occur, just as so many doomsday scenarios have been predicted, always with reliable inaccuracy. The year would be 2027.

Since bidding adieu to this curious character of skilled busmanship and ripping yarns, his tale has occasionally popped into my mind, but, with equal alacrity, popped back out again. I never seriously dwelt upon his premonition. Until two days ago.

There is a certain folly to confessing one’s belief in God even to believers of God. For, the reason why one person believes in the deity may not necessarily accord with the reason why another believes. Confessing one’s own belief therefore has the effect either of ushering in some wearisome or fascinatingly revelatory theological discussion, or of instilling unwanted doubt in one’s mind, on a subject the final evidence of which will be acquired at a time when it will be too late for either debater to declare to the other, “I told you so.”

So, I have no desire to instil panic in you or to urge you to prepare for the cataclysmic event of which my coach driver foretold, or to endeavour to persuade you of the rightness of his premonition. For, if it does not happen, then it will not have happened. And if it does, you will either survive it and be thankful, or not survive it and be well out of earshot before I even had a chance to shout after you, “I told you so.” But I will at least tell you what the event is supposed, as related to me, to be.

It is that the poles of the Earth will in the year predicted, 2027, abruptly turn through 90 degrees, so that today’s south and north poles will come to lie upon our equator, and the equator of today will cease to be the extremity of our day’s-length turning circle and will instead become a line of longitude. And, by the effect, the Ordnance Survey map’s difference between magnetic and grid north will extend to a difference of said 90 degrees or so, assuming the Ordnance Survey’s maps are by that time even of the slightest application.

Perhaps, on reading that, you will burst out with laughter much akin to that which I, in 1982, had, upon hearing the same tale, to stifle, to avoid betraying an air of condescension vis-à-vis an ostensibly honest, simple Dutch family man who happened to be driving my tour coach.

But what wiped the smile off my face two days ago was this report:

It’s in Dutch, appropriately enough, but I’m sure the news is reported elsewhere (Belgium rarely enjoys the thrill of a scoop). It says that we pump so much water out of the ground that this is having precisely the effect described by my coach driver friend, albeit still on a small scale: 80 centimetres in 17 years. Of course, we pump a great deal out of the Earth besides just water. But whatever we pump out of it, some scientists, at least, believe that that is a contributory cause to this phenomenon.

If the phenomenon is accurately described by the scientists, then one is left to ponder whether it might in fact be the inception of the phenomenon described to me by that Dutch coach driver. Or whether it is another phenomenon altogether, assuming it’s even true.

Howbeit, there is no cause to panic, and panic would, in any case, be to no avail, for all the aforementioned reasons. But pondering is always a worthwhile activity, and, if the Dutchman was right, we may, at our ease, ponder such odd coincidences, or phenomena, or causes for, well, at least for the next four years. And then, we can either burst out laughing, or we may politely stifle our guffaws.