Simon Jenkins is a journalist who I will stop to read. And what I’ve read of him in the past is very redolent of what he wrote on 10 June, which is this. It is Mr Jenkins’s view that honouring the war dead causes wars. That’s very bluntly put and, were he here, he would doubtlessly rush to fill in a bit more detail. But his view is more or less that, by wallowing in past national pride, we pave the way to our involvement in future military conflicts.

There is a certain empirical truth in what he says. Countries for which one has to delve back far into the past to find any military engagement tend to be those about which there is little or no fear of a future military engagement. Of all the nations that were not caught up in the Second World War, how many have been involved in conflict since then?

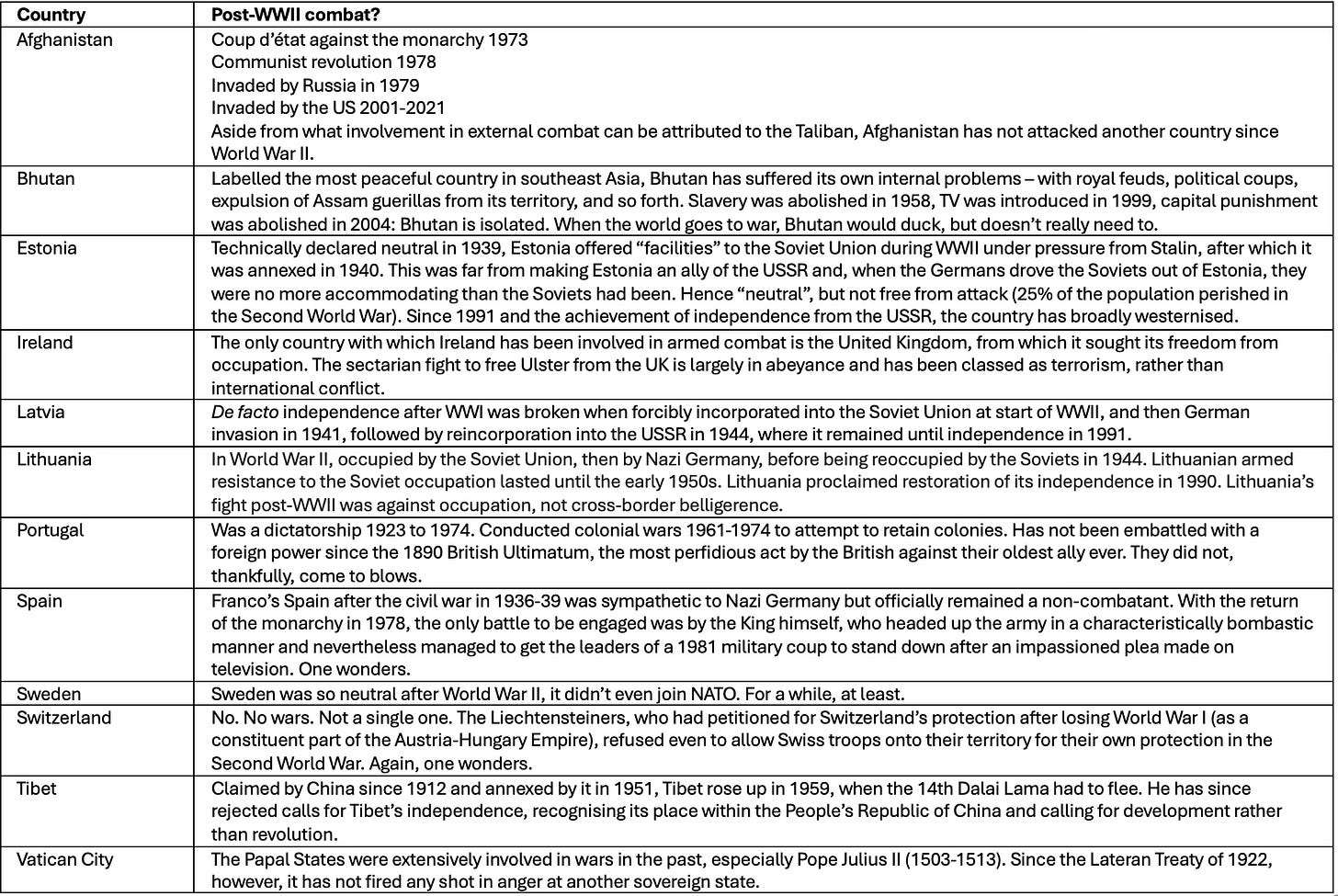

Here are the countries which were not involved in the Second World War and notes of their post WWII belligerent engagements:

The cases aren’t entirely comparable, but none of those that proclaimed neutrality in World War II (and yes, I know about the Netherlands and Liechtenstein and the rest) has played a key role in military engagements occurring since then. The US, the USSR, Russia, China, France, the UK, they’ve all rattled sabres whilst diligently remembering and honouring the fallen of two world wars (and everything since).

What the people doing the honourable remembering remember, however, is in large part not the sacrifice of the unknown warrior whose flame licks their feet every day as they nonchalantly walk past the Brussels Congress, or Westminster Abbey, or the Place de l’Étoile or Arlington Cemetery. It is their great uncle this or their grandfather that whom they remember. And they remember the deprivations they themselves lived through or were told of by mothers and fathers, grandparents and relatives scattered afar, because World War II was not a soldiers’ war (and here the poppy-sellers are cute): it was a peoples’ war. One in which the greatest suffering was not endured by men bearing muskets, dressed in cuirasses and red coats, but by men and women herded into concentration camps, piled into cattle wagons, blitzed to smithereens in their sleep, and evacuated to hosts of questionable moral standing in the rural idyll of the British countryside. After Passchendaele, the men in khaki returned shell-shocked. After the fall of Berlin, the whole of Europe, Asia, good parts of Africa and the westerly outreaches of America were in shell-shock. Today, what are remembered are not the dead of Normandy and Dunkirk: the memories are in fact much closer to the home front, because that is where they have been planted in the minds of the sombre victors: surrogated memories of others, kept vividly alive lest we forget why they fought; and lest we omit to remember why we will ourselves fight, come the next call to duty from some Boogie-Woogie Bugle Boy of Company “B”.

Why did the fallen fall? Did they make the ultimate sacrifice, or was the fresh bloom of youth plucked from under them? Because Lord Kitchener pointed at them from out of a poster? Because to do so was their bounden duty to the flag? For the pledge of allegiance they’d been taught to say with gusto every morning of school? Because they were drafted, like pigs to the slaughter? Because they enlisted out of a sense of indignation at what their enemy was doing? To defend their own borders, those precious black lines on some map? Because they were told to? Or because it was the only career option available to a black boy descended from slaves?

The Andrews Sisters song Boogie-Woogie Bugle Boy of Company “B” was presented in a Walter Lantz cartoon film in 1941, depicting the bugler as an outrageous trope of questionable racial taste.

The iniquities committed by the Wagner Group in Ukraine were committed without question. Yevgeny Prigozhin said slaughter children, so they slaughtered children. The consequences of not doing so were clear: they would have been slaughtered themselves. What were the conscientious to do: desert? Many of them took another route to their own salvation: they shot themselves in the foot; or they shot their commanders. Whatever they did, they did it whilst following their own interests, or perchance a banner, a vanguard, a flag. Egged on by the ghosts of past conflicts whispering in their ears, “For God, for England and Saint George.”

Flags represent clans, families, kingdoms and nations. They are a rallying point for troops when it comes to an army’s prime function: to defend those who employ it, and whose flag they follow. In the years after the Dark Ages, about 1,200 years ago, that’s when nation states saw their genesis. Knights arose replete with the spoils of wars and imposed taxes on agrarian communities in order to finance armies that would win more spoils and guarantee the peace and protection of the tax-paying plebs. And while the farmers tended their crops and their cattle, skilled crossbowmen, artillerymen and horsemen would venture forth to repel the invader who dared broach their hallowed frontier.

In a modern context, this was little more than a protection racket. The knight of the realm was essentially a thug, raised to the peerage by a grateful capo, the king, thankful for the knight’s unrelenting determination to kill and steal, granted a portion of the kingdom under his ever-gracious care and tutelage—for the time being, of course—until a foot was put wrong and the honoured servant would be put to the knife. All with due honour, of course.

The parallels between aristocracy and organised crime are frighteningly similar. Where they differ, however, is in one essential respect. Mafiosi will lure away from people’s families, under an aura of long-standing tradition, the young men to work as their runners, shooters, protectors and valiant enforcers. These men are armed and ruthless. Bound under a bond of silence and secrecy, they do the bidding of the senior mafiosi, like middle management of some international corporation. But what the mafia do not do, which governments do do, is to exact taxation as a means of protection of the populace and then proceed to pressgang the populace itself into its own defence. That is as if an insurance company were to exact a premium to cover an insured risk and then, when the risk is realised, require the policyholder to take action himself to abate the risk. Any policyholder who acts in such a manner is one who is confident in the ability of his insurer to refuse cover (in fact many policies require the insured to mitigate the very risk that is insured).

So, if young men enlist to take up arms on behalf of the nation when its darkest hour doth dawn, then they should at least be reimbursed their income tax for a couple of years, don’t you think? And, if they are killed in action, then their estate should be repaid their entire income tax over their entire lifetime. Because the deal with taxation is protection. And if the government is unable to provide protection in return for the tax it has demanded at gunpoint be paid to it for that protection, then the least it can do is refund the money it extracted under false pretences whilst conscripting the taxpayer to protect himself, in light of the protector’s failure to do so.

Instilling that as a principle—that, at least, if we call you up to fight for your country on top of demanding tax for your protection, and then you get killed, the family you wanted protected by your country will get back the tax you paid us, because we screwed up on our side of the bargain. And that might just impel government ministers to fight tooth and nail to avoid warfare, lest the populace of their nation—the shareholders of their corporation—pursue them for negligently causing their financial support’s death. When avoiding war becomes avoiding your financial liability to the soldiers you conscript (just as an employer owes liability to workers towards whom it fails in its health and safety duty of care), then we might see some more serious attempts to avoid armed conflict. And failure to do that could perchance be equated to negligent bankruptcy, incurring the personal liability of the nation’s directors.

Of course, the likelihood is remote. In fact, the likelihood is more remote than that of a gesture of gratitude from an honourable mafia godfather. Instead, the poor bugger gets his name on a stone in the town square. And, once a year, they come with caps and poppies to salute his sacrifice to the nation that cheated him out of his life, and still extracted the protection money.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning, we will remember them. Aye, but they won’t do a damn thing to prevent the whole sorry saga from repeating itself.

The obvious retort is that, if our enemies are to take us half seriously, then they must believe that we will throw all our manpower into the fight against them. And when they call our bluff, why, then we must throw all our manpower into the fight against them, because we cannot be found to be bluffing. Our people are our chips on the world’s roulette table, and we wager our chips against the great croupier in the sky. We do not do this willingly, we do it because it is the way of the world. We do not do these things because they are easy. We do them because they are hard.

And we do them because we don’t do them.

You do.