A London Symphony

Ralph Vaughan Williams was never quite all he seemed. Sunday musical excursion #33.

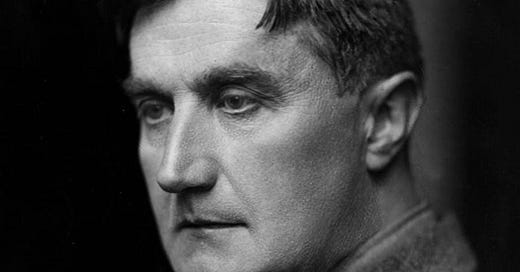

Image: portrait of Ralph Vaughan Williams, 1920.1

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958) was an English composer of early musical talent and late musical development. He was educated at public school (that’s private school in other countries) and Cambridge University, and his first major work wasn’t written till he was 37 years of age (A Sea Symphony, completed in 1909).

Today, I want to talk about A London Symphony by Ralph Vaughan Williams (first name pronounced Rafe), and to do that I will need to fill you in on some background. In case you think the subtitle refers to his ménage à trois with his dying wife and imminently to be married girlfriend 40 years his junior, it doesn’t. There is a strange sense among all Vaughan Williams’s biographers that the domestic arrangement was of greater platonic purity than even the saints among us could imagine. But that fact retains its relevance in what follows.

Musicologists divide Vaughan Williams’s nine symphonies into three groups: the early three, the middle three, and the late three. All of the last of these were completed within five years, and a year prior to his death. That’s quite a feat, three symphonies in five years in your eighties (although the seventh symphony is a reworking of film music he composed for Scott of the Antarctic). I was once out in my car with the director of the Scottish National Orchestra when Vivaldi came on the cassette player—a movement from The Four Seasons. “Is that Vivaldi?” Guy asked, and I said yes. “Which piece in particular?” I was surprised he didn’t recognise probably Vivaldi’s best known concerto. “Honestly, they’re all the same,” said Guy. He was right, they are. It is not a mistake that you make with Vaughan Williams.

His first three symphonies proved long in the gestation and, oddly, for all it is for his symphonies that Vaughan Williams is most widely thought of today, his passion lay elsewhere, in the music of the Tudor period and folk songs (he collected them on his travels, just as the Brothers Grimm had collected their fairytales on theirs).

The first (Sea) symphony is composed for orchestra and voice. This is a style that was occasionally used by probably Vaughan Williams’s closest musical friend, the Austrian Gustav Mahler; the two men would frequently play their latest compositions to each other for mutual appreciation and comment—what true friendship ought to be—and this would likely be a format the two admired. Vaughan Williams was also a rare student of the French composer Maurice Ravel, who otherwise seldom did teaching work. He recognised in Ralph Vaughan Williams a composer unlike any other he had taught, remarking in addition that the student’s progress was not to be noted by the week or day, but by the hour.

Scholars recognise that, after Vaughan Williams’s period in Paris under Ravel’s tutelage in 1907 and 1908, his style became noticeable lighter, as it shed the remnants of the Teutonic weight that all English composers’ styles had laboured under in the 19th century, and Ravel likely kick-started RVW’s productivity. Ralph Vaughan Williams was therefore the first of what I would call the British eurocomposers, since those Englishmen who came after the London periods of Haydn and Handel had done just what the Germans had done before them. In a like vein, Vaughan Williams did a lot of work in Europe and the United States after the second world war for the Society for the Promotion of New Music, such that he shared a zeitgeist with (Robert) Schuman—the politician, that is, not a composer. Having stylistically broken with Europe’s influence on English music, Vaughan Williams did much to bring Europe together again, as part of the post-second world war rebuilding efforts.

Not only did he write for the movie theatre (soundtracks for five films), but one can recognise his musical influence generally in films of the late 1940s and 50s, with snippets of soundtrack that emulate his light style. He’s known for his Wasps, The Lark Ascending and much else that is of the natural world, including, unsurprisingly therefore, a Pastoral Symphony, albeit quite unlike those of either the Russian (Alexander) Glazunov or the German (L. v.) Beethoven. And yet, we confront with that a conundrum, for isn’t the function of a title to tell you—at least approximately—what it is that you will hear?

It’s at this juncture I feel it necessary to point out something about this composer’s relationship to his music, which I summarise as being: people decide what it is that his music says to them; he knows what it said to him, but they should not ask him about the latter in order to reach a conclusion on the former. Broadly, much music in early times was inspired by the church, in a formal sense, and the telling of stories in the oral traditional of the minstrel (who would normally sing of love). There was never any question in those days but that the audience knew what the music was meant to mean: either from the part of the mass it was written for or the words to the ditty in question.

Later, a style of dance might indicate what a tune was intended to convey, but it was not until into the—confusingly named—classical period that music became something about which the meaning needed study, or intense listening abilities. Two traditions developed: programme music, where the tune itself describes an event, an emotion, or a story. The best example would be Sergei Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf, in which the instruments of the orchestra are supposed to represent characters in the story that is told, usually by a narrator. Richard Strauss’s Alpine Symphony musically describes the events encountered whilst climbing a mountain in Bavaria (we think it’s the Zugspitz).

Absolute music, on the other hand, makes no attempt at representing anything in particular and, except where Vaughan Williams expressly wrote about a story or on named themes (clearly Scott of the Antarctic and operas are programme music—even if he described only one of his five operas as an opera), he insisted that all he wrote was absolute music: “It never seems to occur to people that a man might just want to write a piece of music.” In response to the reception given to one of his last works, The Pilgrim’s Progress, he said, “They don’t like it, they won’t like it, they don’t want an opera with no heroine and no love duets—and I don’t care, it’s what I meant, and there it is.”

There is a pointlessness to all this speculation about whether music contains meaning, whether that meaning is particular to the piece in question, and what the composer actually intended the meaning to be. On one aspect, I think Vaughan Williams is categorically wrong, however: it is not possible for a man just to want to write a piece of music. Because, if AI needs impetus as to what to write, then surely so does a man?

The second symphony that Vaughan Williams wrote does not, technically, have a number. Instead, he gave it a name: A London Symphony. Immediately, he corrected himself; rather, it was a symphony by a Londoner, adding in relation to the third, scherzo, movement, “If the listener will imagine himself standing on Westminster Embankment at night, surrounded by the distant sounds of The Strand, with its great hotels on one side and the New Cut on the other, with its crowded streets and flaring lights, it may serve as a mood in which to listen to this movement.”

I might cynically retort here that that is pretty detailed visualisation for a work that is not programmatic. Perhaps the one musical notation with which London is most closely associated is to be heard, in fact, around the world: the Westminster chime, which is played (at least) twice in this symphony. You can’t incorporate that into music and expect it to be understood as what you will.

I think what we need to look at is not each musical element, as representative of a particular thing, but of the music as a whole representing an overall mood. In this case, it is the mood of the composer, at the time he was composing, in the place where he was composing. The scholarly split of Vaughan Williams’s symphonies into three lots puts the second and third in the first such lot. Neither of them is what it says it is, albeit I am not a scholar of Vaughan Williams: nonetheless, for me, the Pastoral isn’t pastoral, and the London is allegedly—according to the composer—not about London, it’s simply by a Londoner. But, by Vaughan Williams’s way of it, I do not need to be a scholar of him to understand his music, for that will tell me what perhaps provoked the emotion that I hear expressed in the music, but I don’t need that knowledge in order to feel the emotion. And, what scholarship might even do is use evidence to direct my enquiry away from the emotion’s true source (like the decimal point that told us spinach is so nutritious).

Let’s dwell for a second on that passing statement above: Vaughan Williams’s Pastoral Symphony, his third, is not pastoral. Not by Glazunov’s standards, not by Beethoven’s and not by yours or mine. Pastoral, the life of the country shepherd, is twee and soft-tinted, simple and wholesome; it is in fact Ludwig van Beethoven (take a listen of the link: played from memory, for freshness and spontaneity).

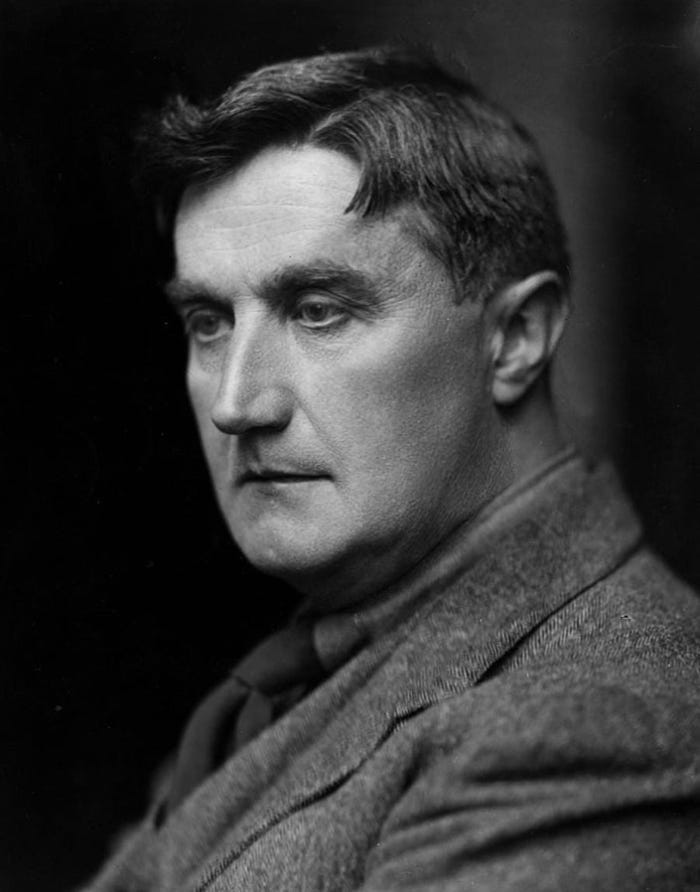

Image: Ralph Vaughan Williams in uniform during his service in the First World War.

An event separates the Pastoral of 1921 from the London of 1913: the First World War; and it was not by sheep that these pastures were inhabited; they were a wasteland, from which the sheep had been obliterated by endless tons of explosives. It is, I find, strange to bed the London and Pastoral down in the same scholarly category, given the war in which the composer served, and that for its entire length, which is nestled between them. I would hesitate to say the war did nothing to upset the connectivity that exists between the two works. Instead, I would say it reinforces it.

Vaughan Williams finished his second symphony in 1913. In August 1914, when war broke out, he signed up. He was 41 years of age. He was public school and Oxbridge educated, and yet he served as a stretcher-bearer at the French front, and had understandable difficulty in keeping up with his much younger comrades as they scrabbled around in the pitch dark and mud succouring to wounded soldiers’ needs. He switched to the Royal Artillery in 1917 (in later years, he suffered deafness as a result of the pounding of the guns), with whom he remained for the rest of the war. He did the full stint; and he survived. He was not even demobbed until 1919, having stayed on with the British First Army as their musical director.

He wrote sacred music, hymns, and an opera based on The Pilgrim’s Progress by John Bunyan, even though he had lost his faith during his adolescence at Charterhouse School. But his name is not associated, unlike those of Edward Elgar and William Walton, with great moments of British patriotism. His œuvre is replete with his love of the folk song, the music of simple country dwellers. Not for him Pomp and Circumstance, Orb and Sceptre or the likes. He twice declined a knighthood, which is very telling. A knighthood is recognition by the State of the recipient’s contribution to an area of life. You can view the refusal as one of three things: that such awards are meaningless to someone who puts substance over form; that the recipient considers themselves undeserving of the honour; or that such honours constitute unwanted bribery. It’s not necessarily acquiescence to accept them, but it is a rare statement to decline. Except that, again, Vaughan Williams didn’t tell anyone why he declined. He never revealed his innermost feelings. And that is most odd for an artist.

From August 1914 to February 1919, he served his country as a wartime soldier, going deaf as a result, and in the panoply of his works, there is, by his way of it, not one whisper of that to be found? Can it be that it would be left solely to the pacifist Benjamin Britten to write a War Requiem? What’s more, he spent four-and-a-half years as a uniformed servant to his King and country, along with hundreds of thousands of other men and women, many of whom never saw home again. What, remind us, was the reason he would have deserved this knighthood?

You should listen to the Pastoral, to its trumpet voluntary in the second movement (which I’ll swear John Williams cribbed as inspiration for the more thoughtful moments in Born on the Fourth of July, the Tom Cruise film based on the life of Vietnam vet Ron Kovic), and to its lonesome, wordless female voice, ending the symphony in desolate tranquillity (which is worth comparison with the lonely violin ending the second and fourth movements of the London). Listen to it now, and, after the impending disaster, if it comes, you will remember this recommendation, and you will nod and say, Graham was right. That’s what ‘after a useless war’ sounds like.

But we’re not quite that far yet, we’re still in 1913. Vaughan Williams would later amend the score for A London Symphony, on several occasions, so that today we have the original score of 1913, a definitive version from 1936, and two intermediate versions, of 1918 (implying he was reworking the score even before the end of the war) and 1920. So, why did the symphony that had taken Ralph Vaughan Williams until his 37th year to compose then get revisited by him post-war for a further 18 years?

Besides the intervening war, he more particularly lost in it, at the Somme, the close friend, George Butterworth, who had encouraged him to write it in the first place and to whom it had been dedicated. The 1936 version is the symphony as it was finally published, with all that history processed, reprocessed and refined, and that is not the version linked below. Rather, there you have the materially different 1913 version, about 16 minutes longer than the later, slimline version. If Ralph Vaughan Williams will not tell us what was in him when he finished this symphony in 1913, then we must ourselves explore the 1913 version to attempt to get a feeling for what it was.

I tried that thing with imagining I’m on the Victoria Embankment, listening to the noise filtering down to the river from the original Danish settlement of London, where the Strand Palace Hotel now stands. It is night-time and the lights are flaring. The New Cut is now simply The Cut, and the hundreds of costermongers that would load up with provender here at night are now long gone. And, yes, there is some of that that I can hear in this piece, just as I can hear Covent Garden in Eric Coates’s London Suite from 1933. But that is not what I feel. What I feel is 1913.

The year before 1914.

A London Symphony

Composed by Ralph Vaughan Williams in 1912-1913

Performed on 19 July 2005 by the BBC National Orchestra of Wales, directed by Richard Hickox

By E. O. Hoppé - The Bookman 61 (361), p. 48, PD-US, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=64804985.

Thank you, Graham. I am not familiar with Vaughn Williams music - my tastes seem confined to the earlier woks of Bach, Beethoven, Mozart, Vivaldi. While I listen to Chopin, Tchaikovsky, and others of the romantic era the music is little too mushy for me.