The main difference between a shooting gallery and a rifle range is that, at the former, you’re there for fun and, at the latter, the aim is training in the use of guns.

The gentleman in this photo1 is at a fair just outside Mexico City. The gay, vibrant colouring would indicate that he is merely there for fun, but just outside of Mexico City is a place where these kinds of skills can nevertheless come in handy in a very practical sense.

To his right, beyond the stall-holder, are his targets (he seems to have been assigned column 7). Sometimes simple metal plates mounted on a hinge, so that when they are struck by a projectile they tip over backwards to show a hit, here we have targets in the shapes of animals: dogs, donkeys, elephants, lions and so on; just the sort of thing people need to be trained up in shooting, especially if you happened to be a king of Spain.

Around the target area is the display of tempting prizes: love hearts, footballs and what look like Minions. The prizes are on the gaudy side, intended to have a short lifespan in their winner’s possession, are brightly coloured and large. The average age of the participants is probably reckoned to be the age that lusts for these kinds of prizes, especially if the lust for the prize shown is rewarded with a further prize (not shown) as a consequence of the hit and the win. I’ve never been to Mexico City but what’s the betting that the footballs are sought by well-practised young men who’re probably not handling a firearm for the first time at this stand, and the love hearts are sought by their young ladies, who are goading them along to win one for me, darling? What presents itself as a simple game of skill actually transpires to be a feat of sexually driven machismo.

The way the game is played is to select a rifle from those on offer, whereupon you pay the stall-holder the price asked for so many projectiles (these are usually air-powered weapons, and here you get 15 lead balls for 20 pesos). Using the fairly rudimentary sights and with a fairly accurate aim, you should have a evens chance of hitting one of the targets (sometimes they move along a chain). You can see whether the barrel of the rifle has been misaligned (a popular form of cheating by stall-holders), but not what might have been done within the barrel to divert projectiles by playing with the rifling. Therefore, like Nicolò Tartaglia, one needs to observe carefully the trajectory adopted by the first couple of projectiles in order to discern how far the projectiles err from the presumed path to the actual. Being made of metal, the targets give a satisfactory clang when struck, but must nevertheless fall to be counted: stall-holders are not noted for their use of oil. For a certain number of hits the customer wins a prize (three levels at this particular stand: tumbando 12 (doce) figuras, premio chico means 12 targets (figures) knocked over, token prize, all the way up to 15 targets earning the premio grande—a grand prize).

Clearly, the aim is the fun of shooting the targets and the satisfaction of that clang and the fallen target. One wonders why the prizes are offered at all, if that’s the purpose. I have known Schützenvereine in Germany, where the prizes are silver cups and trophies, which need to be returned the next year, albeit with the winner’s name added to the base. The prize is the honour of winning, except that some whose names appear several times are either too good for the club, or the club hasn’t enough members.

There is, as far as I know, no definitive rule book on the whys and wherefores of running a fairground shooting gallery. So, I could tell you that stall holders cheat, but that they need to temper the cheating because otherwise no one will ever try their hand at their stall. Or I could say that a reputation for cheating is so widespread among fairground attractions that it’s obvious they cheat, and so no evidence is needed. Or I could say that the duly earned reputation for cheating makes no difference because of the itinerant nature of most fairground attractions and the passing nature of their clientele. I could give an opinion on why the stall-holder has chosen to decorate her gallery in fuchsia, and not camouflage, or on the real reason why footballs and Minions are offered as prizes (above, I merely speculate). I could observe a shooting gallery and perhaps be able to estimate the ages of customers, whether they are male or female, whether they are accompanied and, if so, whether by persons of the same or the other sex, what clothing they wear, their estimated income. And, possibly most important of all, I could tell you how much the premio grande costs wholesale, whether that is more than or less than 20 pesos, and how often it gets won. And those factors would give us insight into the financial risks taken when deciding to go into the fairground shooting gallery business, the types of people who are attracted to shooting galleries, and perhaps even why they’re attracted to them. Whether you are acquainted with shooting galleries or not, the answers to all the above questions are predicated on one single bold precept, and it is this: nothing is for nothing, even if the difference it makes cannot be measured.

If we step back from our modern world to view mankind’s development as a complex path which would seem always to have inexorably moved forward in terms of its technological advancement (and never backwards), then we can surely pat ourselves on the back as having been part of a process instigated by our forebears back when the plough and lateen were adopted from the Middle East to revolutionise life on land and at sea and culminating, for the time being, in a solid state technology that could take us to the moon and back (so they say). Or we could pin the whole thing down to expedience and happenstance. And which is true would, as with the purpose behind footballs at shooting galleries, largely depend on speculation.

The law knows a process of criminal evidence known as the but for rule. It’s intended to provide clarity and simplicity in deciding the level of someone’s negligence or criminal guilt: the test is whether the harm of which the defendant is accused would have come about but for their act or omission. Was their acting fundamental to the resultant prejudice? The problem with this test is a little like defining the list of people to thank when you win an Oscar. The Oscar is awarded to the best actor and, to be the best actor, you need to act the best, and the way an actor acts really has little or nothing to do with how the director directs and how the producer produces. But they get thanked by the actor, along with his wife, children, dogs and mother and father. And, in fact one might include their grandparents, and their great-grandparents and the immigration officer at Ellis Island who admitted his great-great-grandfather as an immigrant to the States in 1875. Where do you stop? Because but for that immigration officer’s stamp of approval in 1875, this actor would never have been in that film and could never have won that Oscar. Therefore, it is with circumspection that courts apply the but for rule.

Nevertheless, when we track the development of inventions and discoveries across the ages, from that Arabian plough and Mediterranean lateen sail all the way to the here and now, and even on into the future, what becomes apparent is that inventions that change the world do so at a flash, and are therefore unlikely to occur simultaneously through several unrelated agencies. Some inventions can be seen as in and of themselves being the cause for population rises, or falls. And some discoveries lie ignored for hundreds of years before coming to application, such as with Ptolemy’s observances of the stars. Still, without them, would we ever have known about longitude? The question, therefore, to dwell upon is whether the way things are is the way things are because they would have been that way anyway; or whether the motivation driving things to be the way they are is somehow dissembled from the observer’s eyes.

Returning to shooting galleries for a moment, and the notion that nothing is for nothing, our Mexican example can in many ways be viewed as a microcosm of our world, predicated on one single fundamental: that, to be financially viable, the stall-holder must attract sufficient clientele. She will have her pitch fee, which could be upward of 1,000 dollars a day, and the cost of the slugs, lighting when it gets dark, and the prizes. Whether they come off the gross profit or are calculated into the price charged depends to some extent on her monopoly position in the market: if she’s a weak market participant, she’ll take the hit of these costs; if she is strong, she’ll defer them to the pricing. And she may be the only shooting gallery on the site, but that doesn’t mean, on an alternative amusements basis, that she has a monopoly.

If the shooting gallery is a microcosm, how does the real world shape up in terms of its macrocosm-ness? I suppose that the financial and economic aspects of running a shooting gallery are in some way akin to those of running a government, with one major difference: governments don’t pay tax. But governments decide what colour to paint their stalls to make whatever they sell more palatable, to attract the customer more willingly. Prizes are on offer, but only for 15 hits out of 15 shots. Yes, there are token prizes for those who achieve only 12 or 13. But the vast majority of young males who hand over 20 pesos don’t do so for themselves, unless you include getting her in the sack later that night. Likewise, when governments express sympathy with the victims of crime, it’s not for the families of the bereaved that they do so.

What view you adopt of what reason there is for doing what action will ultimately do much to change your view of the action. Either you will find fuchsia a delightful colour for a sideshow stall or you’ll find it in intrusive seductress designed to induce a Mexican’s girlfriend to egg him on to test his prowess at shooting. Whichever view you adopt is unlikely to alter the outward appearance of the action. The motivation remains a secret, until its owner reveals it.

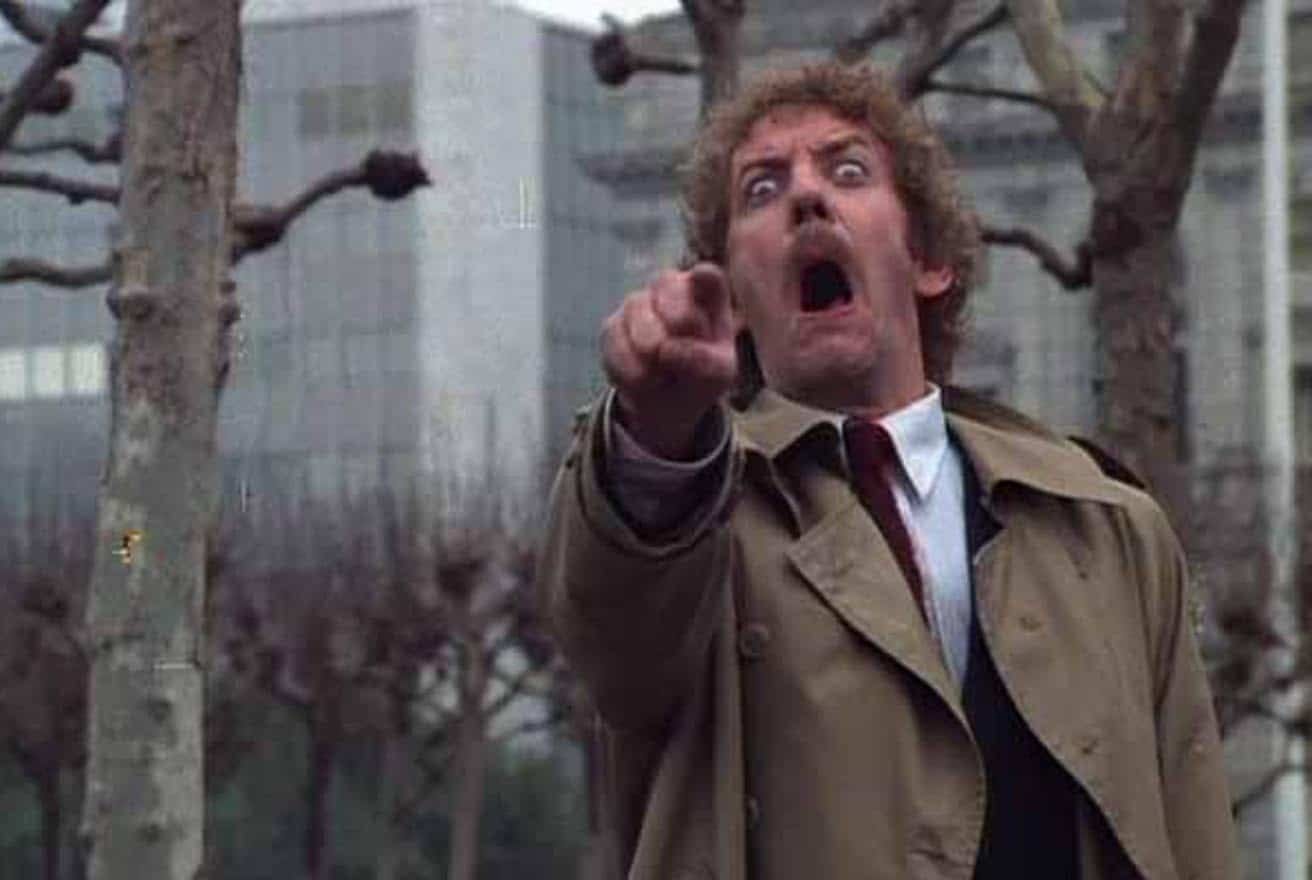

I was recently moved to contemplate the remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers (with Donald Sutherland and Brooke Adams). The movie depicts a city (of San Francisco) invaded by strange, plant-like pods that build a cocoon around human beings, suck out their innards and then reconstitute the humans as themselves. The one thing they cannot reconstitute is human voice interaction. But otherwise the replacement is perfect: from seeing them, no one can tell the real humans from the reconstituted ones, aside from an absence of emotion.

Perhaps the most shocking evidence of this, as per the film that is, is the fact that, at the end, one of the few characters who has escaped being snatched espies Donald Sutherland in the street and, with a stage-whispered psst, attracts his attention, only to be fingered by him to all around that she is one of … them. It’s shocking because the street scene in which this happens looks just like any street scene of San Francisco.

The all-pervading message, from the opening to the final shot is don’t get snatched. And, aside from the touch tag aspect (when children play the game, they avoid being touched; here people have to avoid falling asleep), the film presents food for thought that goes way beyond the simplistic notion that the principle of a children’s game can end up with a take-over of the world.

When the film ends, the city doesn’t look like a nuclear winter or an overgrown expanse of urban desolation, such as in Wells’s The Time Machine, nor do we have the kind of changes that Woody Allen has to cope with in Sleeper. No, none of that. It looks exactly the same as at the start of the film. What the invaders have done is alter the state of the inside of the inhabitants of their new world, but they have changed nothing of what is external. Seemingly, the world ticks along just as it had before. There’s no guillotine on the street corner. No masses railing at the gates to the Winter Palace. No Batistas fleeing out of Havana to Florida. Invasion of the Body Snatchers is all about a revolution that nobody notices.

In the real world, Mr Biden’s legacy, so he would have it, is to be leaving a USA that is vastly better off than the one he inherited at the start of his presidency. The problem with that is that most people questioned by pollsters say they can’t see what’s better now from what it was before. So, if you can have four years of government that nobody seems to have noticed, perhaps you really can have a revolution that nobody notices.

Maybe you can enter an entire population’s psyche and change the whole way people feel and think and react about themselves and other people, and leave no trace of your intervention. No needle-puncture holes. No Saydnaya prison. No Clockwork Orange. No Ipcress File. Just … well, just universities, and schools, and management schools, justice systems, economic figures, political figures. Nothing more malevolent than a carrot or a stick. And smartness. Not smartness like knowing your 12 times table, not that kind of smartness. It’s simpler than that: smart is saying yes when yes is what people need you to say.

The challenge for the body snatchers is this: We will make them act and think about their world differently from their parents, their grandparents. And we don’t mean white Christmases. So, do we really view our world so differently now than did our parents and grandparents, and do we still perceive that same world as having not changed one iota? Let me leave you with an example.

Last week a colleague at work talked about her holidays in Thailand. She said it is a beautiful but humid country. Then she pulled a face, and referred to some of the men. I asked what she meant and her allusions became less opaque. In short: men who travel to Thailand and equip themselves with young girls, in which the definition of young was not further stipulated. It is not especially shocking to see men and girls in each other’s company, although it is if you gain knowledge of the nature of the relationship between them. But the greatest shock of all comes with the sheer brazenness of a public display of something that is there for all and sundry to observe, draw their conclusions and then … ignore. Passers-by ignore it because it’s none of their business. Police will ignore it for adequate payment. And the girl’s family will ignore it, because tonight they have food on their table. Because it’s smart to ignore it.

By A01333649 - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=35929753.

Good observations, Graham. And you are correct, it does describe America today. It has taken "them" roughly one hundred and fifty years to achieve it, but the oligarchs from Colonial America through the Civil War. finally got it through their descendant's thick heads that the way to achieve their over long goal was the dumbing down of our children. On November 5, 2024, they achieved what their ancestors failed to do in he Civil War - change the United States from a representative republic to a theocratic aristocracy.