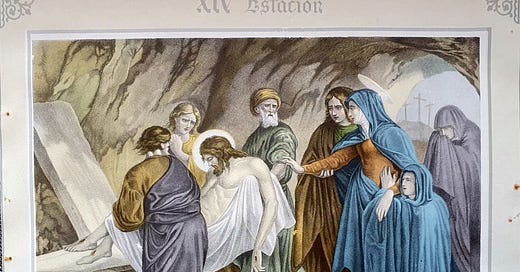

Image: Jesus is laid in His tomb. By Valdavia - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=113494229

Easter is when the clocks change here in Europe, this year at least. Like Ramadan, it’s a religious festival that depends on the phases of the moon, rather than falling on a fixed day, like Christmas.

Last Christmas, I spent time to muse about the true meaning, not the symbolism, but the implications in the real world, of the circumstances surrounding the birth of Christ (you can see the relevant articles at the foot of this post):

- Joseph’s dedication to a woman who’d become pregnant other than through their own mutual act;

- a question as to why Mary, who was not yet Joseph’s wife, came with him to Bethlehem, the city of his birth, for the census; but was it the city of her birth?

- the fact that the innkeeper, a featured supporting role in all school nativity plays, gets no further mention in the Bible, and the fact that he clearly does not relinquish his own bed to the weary travellers, of whom one is pregnant, coupled with a strong feeling that, in a town overcrowded to the point of house full signs, he will almost certainly have charged them for use of the stable;

- a question of why the Host appeared to shepherds on the hillside, instead of the townsfolk in the crowded city. Even as a city, Bethlehem was not a large place at that time, so why did the people of the town not also come to see the new-born babe? Maybe they did (only Matthew really mentions Jesus’s birth, even though Mark’s gospel is based on Matthew);

- why the three wise men brought gold with them, a commodity that has zero meaning in the context of faith and eternal life (the rich cannot enter heaven, according to Jesus);

- the incredible journey by the three wise men, it is thought, from either Teheran in Persia, or Yerevan in Armenia: a whole month on camelback, carrying very expensive gifts, and no mention whatsoever of a retinue, though it’s hardly credible that they’d have travelled unprotected all that way: they were important enough to gain an audience with King Herod, and important enough for him to exercise diplomacy with them, and wise enough not to fall into his tactical trap before embarking on their one-month camelback trek back home, after which we hear not a murmur from them ever after.

At Christmas, parents take their excited children to pantomimes to enjoy simple pleasures of the theatre, in which a whole different play is projected over the kids’ heads to the adult chaperones. This the mummies and daddies know even as they purchase the tickets, so it will come as no surprise to them that Christmas, and also Easter, are, they too, loaded with childlike joys, as also serious, adult symbolisms.

For, now, we come to His death. For us, here on Earth, just over a quarter of a year later, one season. In reality, it came after thirty-three years: thirty in which Jesus matured, and three in which He preached the word of God and sealed His fate. The first Christian martyr, revered throughout the world, not just by Christians, but also by Jews and by Muslims, who hold Him in reverence, even if we don’t all recognise His station at the right hand of God, the Father Almighty, from which He shall come to judge the quick and the dead.

He was crucified, as was the prescribed manner under Roman Imperial law. He died on the cross, in remembrance of which some of us, yesterday, ate hot cross buns, marked with the symbol of Christianity and highly spiced to remind us of the gall that Jesus was offered and declined as He was nailed to His cross.

I weakened in the supermarket yesterday, and bought some chocolate eggs. The egg at Easter is the symbol of Jesus arising. Joseph of Arimathea, a member of the Sanhedrin (which had condemned Jesus in the first place) had requested delivery of Jesus’s body after crucifixion, which Pontius Pilate had granted. He was laid to rest in His tomb, and a stone rolled before it to seal it. When, on the Sunday, the three Marys (Jesus’s mother, Mary wife of Clopas, and Mary Magdalene) came to find the tomb empty, it was the rolled-away stone that they first beheld.

The tomb itself was empty. So, there is nothing that can symbolise the absence of Jesus’s body from the tomb, for, wherever it might be that you look and see nothing, then there is—in truth—a symbolic reminder of Jesus: it’s a cute contradiction. But, substantively, the only practical symbol of His arising from the dead is the rolled-away stone: which we translate as an egg.

Easter, Christmas, All Saints’ Day, Armistice Day, birthdays, baby showers, funerals, even Spring Break. These are all festivities, ceremonies, rituals shrouded in symbolism, to reflect our deep-set beliefs, our daily practices, our cherished traditions, our hopes and our convictions. We are quite capable of taking the pagan symbol of the Christmas tree and turning it to a cosy symbol of togetherness and devotion to the baby Jesus. And we are equally capable of taking profound symbolism in the spice of the hot cross bun and the meaning of the Easter egg and turning it to an excuse for chocolate joy, and eliding over the meaning, labelling the ritual as simply what people do, without further thought. Banalising symbols for fun is not sinful: sin is that which we do that is contrary to conscience, and what we do not know we cannot be held liable for—suffer little children unto me: in that sense we are like Jesus’s little children. But holding to traditional symbolism as a token of deeply held belief out of a desire to know enriches the devotee with much more than an act of simple, childlike fun.

For the Christian, Christmas is important: it is the season of birth. But the travails of Jesus over a whole week betoken a season of rebirth. That is the crux of Easter, but it is by far not the whole story.

Palm Sunday, Jesus’s betrayal on Maundy Thursday, His execution on Good Friday and His rising on Easter Sunday are of far greater portent than the resurrection alone, for they describe hardships, not just of Jesus’s life, but of the lives of all of us: how we so easily can achieve greatness, in which adulating crowds bow down before us with palm leaves, and how quickly that can turn to infighting, with those like Peter who seek policy change before recognition of the truth, or like Judas Iscariot, the poor misjudged Judas, who chose adherence to the law of man before devotion to the law of God, and paid for it with his life, who gained profit before righteousness. For Jesus, betrayal brought trouble with the law, which led unavoidably to his death sentence, a placation of the same madding hordes as had proclaimed Jesus’s entry into Jerusalem with hosannas, throwing down palm branches at His glorious parade, but one week previously. How the righteous fall from popular grace at the mercy of a fickle populace that choose their heroes on the most flippant of criteria. In sooth, I say verily unto you: the worst shit you will ever have to deal with in life will not be of your own making.

Easter is a Christian season, but it has messages for all, whether of another faith or of none. Whether you believe or not in the resurrection of the body, the eternal life of the soul, and the forgiveness of sin, no matter.

But, take this from the story of Easter: a recognition of our mortal weaknesses, which we see in Peter, who denies his life’s devotion for expediency; in Judas, who bends to men’s machinations and takes his own life in shame at the enormity of his act; in the three Marys, grieving and bereft of the poor, slaughtered son; of Pilate: hapless, vacillating Pilate, offering panaceas to wayward crowds baying for blood, all for an eternal reward ... of popularity.

And, what of Jesus’s weakness? Well, He was the only one who, throughout everything, remained true to His belief, bent to no will but God’s, dismissed all His mortal doubts, and stayed faithful to Himself until His death. You don’t need to believe in Easter’s message of resurrection; few of us can see ourselves reflected in Jesus: He is merely an aspiration, if anything. It is the reflections we can see of ourselves, whether we be Jewish, Mohammedan, atheist or agnostic, in the turncoat friend Peter, in the confused snitch Judas, in the compromised judge Pilate, in the compassionate mother Mary, that serve as our caution and, indeed, as our inspiration.

Two thousand years after political tensions contrived to create a situation in which a man had to die for the sake of placating a bloodthirsty multitude, the Holy Land is still no more peaceful. If none can agree on the meaning of the word holy, can we not at least this Easter make a start on understanding the meaning of the word peace?

When you crack open your breakfast egg tomorrow morning, whether it’s a hen’s or Nestlé’s, remember the trajectory that Jesus passed along, and the path trodden by all these other characters in His story, for whether Jesus is or isn’t our example, His cohorts are certainly our model; reflect for a moment that, though you will not be crucified on a cross or be offered gall to quench your thirst, or roll away a stone from your own tomb’s entrance, what Easter truly means, to one and all, is the unilateral and unconditional promise of resurrection; whether or not you believe in that, in your heart, will make not one iota of difference. Even Jesus had His doubts.

Eyes of needles

The poor have it. The rich need it. If you eat it, you’ll die. What is it? A clever riddle is always a good riddle, but not if you’re the object of its sharper point. I’ll leave you to ponder the solution, which is to be found at the foot of the article, just above the “Share” button.

The Christmas story

[DEUTSCHE FASSUNG FOLGT HIER UNTEN] Believers in God, in Jesus, in the Holy Spirit, cite the Bible as the source for their belief and yet only two of the four gospels dwell in any manner on the circumstances surrounding the Nativity. Some might regard that as surprising, given the biological miracle that Jesus’s birth entailed (the immaculate conception)…

An interesting, if traditional interpretation. Since you mention the 'fable' of Christmas - even theologians today agree, the 'tax-taking and census' by the Romans, we know was done around our current month of April. The reason the early Christians selected the myth of December was to use the festival of the Winter Solstice to haul in the pagans to accept Christianity. Also the reason for the far-fetched selection of Bethlehem for Jesus birthplace was the connection with King David who apparently was born there - thus an attempt to bring the Jews to accept Jesus as their anticipated 'savior'. Jesus was most likely born in Nazareth - the home of his parents, Joseph and Mary, in April. Jesus according to his disciples (we really don't know first hand the teaching of Jesus as he left no written word himself) referred ti himself as Jesus of Nazareth, never claiming to be the son of God. Whatever, the words attributed to Jesus were definitely words of wisdom. If only most Homo sapiens could be compelled by them, what a wonderful world we would live in.