Harmony is often taken to mean musical harmony, or visual harmony. A well-composed painting, or photograph. Music that is sweet to the ears. Here are a couple of pieces of music. Do you think they are harmonious?

Mars by Gustav Holst, from his Planets Suite.

Bolero by Maurice Ravel.

What about Brahms? Do you think that Brahms is a racket?

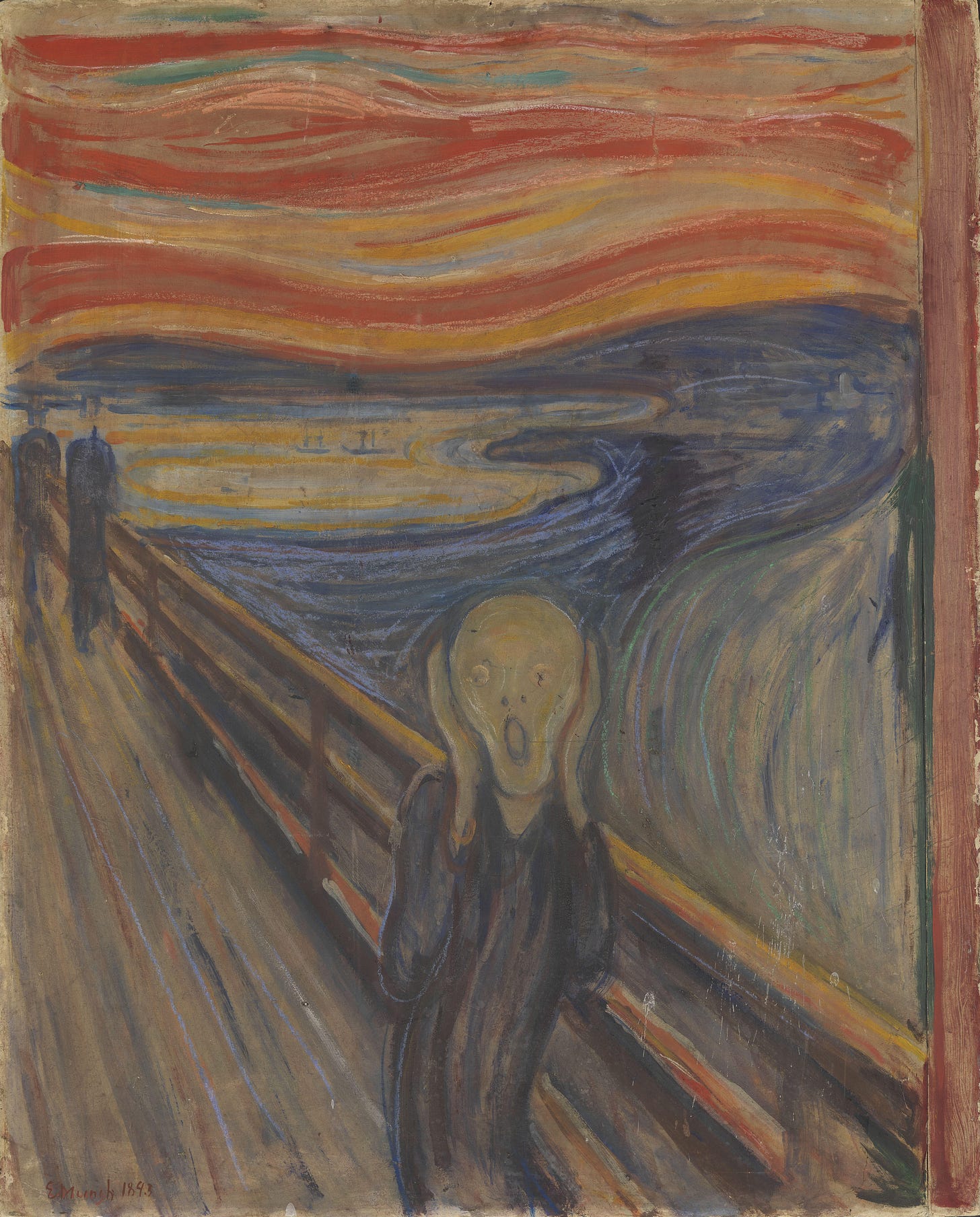

Or take this painting by the renowned Norwegian artist Edvard Munch:

By Edvard Munch - National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=98294410

Is it harmonious? What determines harmony? Is there objective harmony, or is harmony only subjective? Or could it be both?

Look at these scenes of traffic in ordinary streets.

This is one of a series of videos on YouTube under the title Not Just Bikes by a Canadian vlogger who lives in the Netherlands and draws some interesting comparisons between the state of urban planning in the US and Canada, and in Europe. In this particular video, he simply draws attention to the ethos in the Netherlands of instilling a calm traffic cohabitation between motorised transport and pedestrians and cyclists, arguing that this harmony is worked against in North America, where the serviceability of the road in question would thereby be excessively impinged upon.

Which is the more harmonious: a Dutch street with narrow lanes, or a Canadian street with width for four cars? Well, the truth is that they are both harmonious. Mars is harmonious, as is the Bolero, as is Basil Fawlty’s Brahms. They are all harmonious, but the harmonies all depend on a point of view.

The most harmonious street for a pedestrian is one that has absolutely no cars in it whatsoever. One might almost venture that true harmony would exist where there are also no bicycles. And, when you fight your way down a busy shopping precinct on a Saturday afternoon at Christmas, there could be times when a pedestrian will vouch that the most harmonious street is one in which there are not even any other pedestrians. We view harmony in those cases in terms of our ability to get done what we want to do with the least restraint and constriction.

Canadian motorists find nothing disharmonious in their city streets. The pedestrians are safely ensconced on the sidewalks, the road is clear for the wheeled traffic, what’s the problem? The fact that, according to the narrator, the pedestrians are anxious about crossing the road or being in an area with relatively high-speed traffic is of little concern, because worry is not per se danger. The pedestrian is only in danger if they make a mistake. What the narrator argues is that the state of awareness is necessarily heightened for pedestrians on Canadian streets, whereas Dutch streets are designed to obviate the need for awareness, since accident avoidance becomes intuitive, and the consequences of an accident, if one does occur, are less serious. Such is the argument. But, all that aside, which road situation is the more, or less, harmonious? Well, anyone who has driven a car, parked it and proceeded on foot will know that that answer alters radically the moment they step out of the vehicle.

One view might be that harmony is achieved when a higher authority lays down a body of rules, which all those who are subject to the rules then obey. But that is not harmony, it is compliance, and, whereas the net effect may be to avoid accidents to the same degree, harmony is only achieved where it is the road users themselves who come to an understanding of the needs and desires of all the other road users: the pedestrians understand other pedestrians, cyclists and motorists; motorists understand the fears and needs of walkers and cyclists; and electric bikes understand the fallibilities of pedal cycles, etc. The rules that get imposed should be a benevolent amalgam of all these considerations, and not simply a decision imposed from on high because we can.

Is Brahms’s third symphony a racket? It most certainly is not a racket, it is a wonderfully uplifting piece of music, and that is how Basil experiences it as he leans back in his office. But the recollection of his menu-writing duties and his needing to hang a painting disturb his harmony. Brahms is only harmony when the time is right to listen to it (just as traffic-calming measures can only achieve harmony in a city, but not out on the open road). However, a symphony blaring out in a hotel reception is, in Sybille’s view, disharmonic. Unsurprisingly, Sybille and Basil are unable to see Brahms from each others’ points of view.

Is The Scream by Edvard Munch harmonious? It was painted after a sudden psychological experience by the painter when out observing the sunset one day near his home in Oslo. He observed streaks of orange across the sky and first exhibited his work not under the simple title The Scream (or Skrik in South Norwegian) but under a German title Der Schrei der Natur (or The Scream of Nature). I’m not sure who the screaming character is, or even if he is actually screaming, or simply surprised. Perhaps its Edvard himself (who interpreted the orange sky that evening as doing the screaming). Far more interesting, I find, are the distant characters who seem to be walking nonchalantly behind the main subject. The scream itself doesn’t disconcert me. It’s the juxtaposition between the screamer and the nonchalance of the other two figures that disconcerts me. But, is the painting disharmonious?

That is a question that each of us must answer for him or herself, in the first place. But, if all of you reading this were sitting here as I write it and we were to come into a discussion about Munch’s painting, we might be able to arrive at some sort of common ground, what you might call a consensus, even if it is arrived at by a mutual exchange of views.

For instance, I will wager that at least some of you reading this who are already familiar with Munch’s painting will have been surprised when I mentioned the two figures in the background, because it’s not the first element you think of when you recall the painting to your mind’s eye. Often, this painting is talked about in terms of the main subject. The juxtaposition of the sea and the sky may be elided over. After all, it is the subject’s depiction in masks and other media that has made this painting so famous. Nobody pays much attention to the background. But, when I hear your view on whether you find the painting relaxing, or disturbing, or visceral, or feral, and the importance or otherwise you place on the other elements of the work, we could, at least in theory, arrive at an overall judgment of whether the painting is or is not harmonious. And, whilst the fact of being able to do that is of no particular consequence as regards this painting, the fact that that is possible shows … that it is possible. And, if it’s possible on the view about a Norwegian painting, then it should be possible in terms of which of Canadian and Dutch urban planning principles achieve the most harmonious road situation. It should be possible to determine whether Mars is a harmonious piece of music, even if it disturbs the listener as being aggressive and belligerent, which is what it is intended to sound like. And we might even reach agreement on the best time to listen to Brahms’s Third Symphony, and on the best music to play in the background in a hotel reception area.

Maurice Ravel’s Bolero became world famous when it was played as accompaniment to the best ice dancing performance ever, at the 1984 Winter Olympics in Sarajevo by Jayne Torville and Christopher Dean. They devised a routine that leant somewhat on the traditions of the bullfight and the pasodoble dance. It was fiery and exciting, and matched the specially recorded music perfectly. The catatonic ending to the piece is harmonious in terms of the beauty of the interaction between the dancers, in the same way that a tragedy play gives its audience a greater sense of fulfilment than would a happy ending.

The achievement of harmony is often something that is counterintuitive, because our striving for it fails properly to consider the surrounding circumstances. Hence, the unhappy ending to a tragedy play can still actually be harmonious. I’m sure many marriages fail not because of an intention to ruin the relationship but because the parties see the route to harmony as lying in a different place, and they fail to communicate their considerations to each other. A happy marriage is where both parties put the interests of the other partner in front of their own. Then, it works.

Harmony can be upset in the business world when one business partner seeks to profit unduly from the other. Often, a commercial relationship—even one of employment—is entered into not in the sense of a joint enterprise (we’re all in this together to earn a fair wage) but of an opportunity to put one over on the business partner, by making them work longer, under less favourable conditions, for fewer benefits, and less pay. Few shop floor workers will insist that top management should earn the same wage as they earn, since responsibility, risk and power of decision carry a premium in terms of earnings. What exactly the differential between shop floor workers and top management should rightly be will differ, even among both shop floor workers and top management, however. There will nevertheless, provided there is due consultation on the matter, be a level that is arrived at whereby both classes of workers agree the differential is reasonable and makes due provision for all parties’ needs and their respective contributions to the business. If such an agreement cannot be achieved, then that will normally be taken as being the result of one or the other party making, or refusing, excessive demands.

Business leaders that refuse to consult with their workers on such matters will tend, by nature, to demands that are excessive, since the inbuilt tendency to see the viewpoint of one’s negotiating partner is rare. For example, as you decided whether the road plans, music and hotel reception situations above were harmonious, did you consider any viewpoint other than your own? Negotiation itself is a strange creature: what if management said they could up the pay of the shop floor workers by disposing of noxious waste directly into a nearby river, instead of paying for it to be carted away and treated? The savings would be distributed as a pay rise for the workers. One problem with negotiation between two parties is that there is often a third party’s interests in the mix, even though the third party has no voice in the negotiations. Harmony cannot be achieved by two parties banding together in disregard for a third party’s interests.

How harmony can best be achieved is something I do not know, and that no one knows, but that every living creature surrounding us does know. The rest of life on Earth advances its interests only in terms of what it needs, even if it needs to kill in order to survive. That is why it is ironic that we label outrageously selfish behaviour as acting like animals, because animals are not selfish: they stop killing when they are no longer hungry. Mankind advances its interests far beyond that which it needs, and so it must exercise measure in endeavouring to attain the true midpoint balance between need and resource. In the animal world that surrounds us, harmony is endemic; we humans, on the other hand, spend our entire lifetimes in search of it.

If I knew how to achieve harmony, I probably would not be here to tell you. For two reasons: the quest for harmony is a life’s quest, and, like a set of scales that wobbles incessantly around its point of rest, so is life: we wobble incessantly around perfect harmony but never arrive at the point when the needle on the scales is at rest. That is the nature of our life’s journey; at rest is probably, once achieved, the precise place where we all will, in any case, be. It’s a bit like waiting for a fly to land in order to thwack it with a fly swat. (Think about that, but not for too long.)

The second reason is that, even if I had uncovered my own point of rest on my own scales, I could not tell you where that point is in relation to yourself. Your circumstances are, in all but the broadest brushstrokes, different from mine, and you will be aware that the slightest puff of wind can upset a tightrope walker, the slightest waft from a butterfly’s wing can cause a hurricane, the slightest drop of water can cause a bucket to overflow. But what I can tell you is that harmony is achievable for all, and that your happiness is not dependent on the means you perceive to attain it, on position, or money, or fashionable handbags, or fast cars, or flying above the clouds. None of these things will help you achieve harmony, and none of them will detract from your harmony either.

What your harmony will depend on is the manner in which you approach all of these things. If your honest good fortune confers upon you the means to purchase luxury goods, then, by all means, purchase them. If, after purchasing them, your conscience should trouble you, that others elsewhere are starving as you indulge your pleasures, then you should react accordingly because it is not the purchase of luxuries that is creating your disharmony, but the conscience that tells you that you might have acted differently.

Then, you can still achieve harmony by correcting the acts that trouble your conscience. Not my conscience or the conscient that others instil in you, but your own conscience. Yours, no one else’s. It is never too late to correct erroneous acts, and that, as I stated above, is the reason we were put on this Earth: to correct our erroneous acts.

“I have no window to look into another man’s conscience,” said Sir Thomas More. By that, he meant he would not judge another man’s acts. Well, at his trial, after his condemnation, he ultimately did, and how!

I do none harm. I say none harm. I think none harm. And if this be not enough to keep a man alive, then, in good faith, I long not to live.

And whether God chastised him for that outburst of righteous temper ... well, I have no window, either.

Harmony is our quest, and it is within the grasp of us all. Do you think that John and Taupin find harmony in these lyrics? Setting their own pace and stealing the show?

Hello, baby, hello, open up your heart and let your feelings flow

You’re not unlucky knowing me, keeping the speed real slow,

In any case I set my own pace by stealing the show.

Say hello, hello … harmony and me, we’re pretty good company,

Looking for an island in our boat upon the sea,

Harmony, gee, I really love you and I wanna love you forever,

And dream of never, never, never leaving harmony.

Harmony written by Elton John (music), words by Bernie Taupin.

A very interesting column Graham. For me harmony needs a setting. For instance I love Beethoven's third and fifth symphonies, but only if I am alone in my room or listening in a concert hall. Any one talking interrupts the harmony. The same thing applies if I am watching an American football game, I hate Superbowl parties, I prefer to watch alone or with someone who understands and follows the game as much as I.

I am i perfect harmony living in my apartment with my cat as my only companion. Like you say different harmonies for different people - and I'm okay with that.