A few years ago, I wrote a poem, entitled Come. And go. Not much of one, but you may like to read the full thing here, and it’s also in French:

Come. And Go.

I wrote this poetry a few years back when things hit a low point for me. It was at that point that my thoughts turned to those whose lives are at low points, wherever they are; and, within an hour, I'd written this. It's not fantastic, it's not Wordsworth; but it's as heartfelt as anything Wordsworth wrote; a few words' worth, at least.

Va. Et venir

Ce poème a été écrit il y a quelques années. Ici, pour les amateurs de la langue française, le même poème, adapté en français. Cliquez ci-dessus pour la version en anglais. La photo accompagnant le post sur Substack le 15 décembre 2022 est prise depuis l’internet et a été trouvée deux ans après que le poème fût écrit. Ces photos sont faciles à trouver. A…

It contains the following lines:

Give not then this Yuletide your coin to rejoice;

Give solace, compassion, give pity, and voice

To injustice and favour and blind bleeding luck,

And help now your fellow rise out from the muck.

These are sentiments of which I recently found echo in a paper written some years ago by a man who is still to the fore, who advocates I stop treating myself to luxuries.

I cast an eye about my home and sigh resignedly at the fact that luxuries are few, and far between, in this household of mine. Gadgets, I usually drop, or let slip into the toilet bowl; I own one fur coat, a gift from my seamstress, who otherwise didn’t know what to do with it; and my car is a 32-year-old jalopy – which, incidentally, I love. But some luxuries are here. Pretty objects, which some would say adorn the place, others would say, clutter it. I have three bikes, had three cars, have many books and records, and such like, and five drills. I have enough. And I have too much.

But no diamonds, no gold bars, no crypto-wallet.

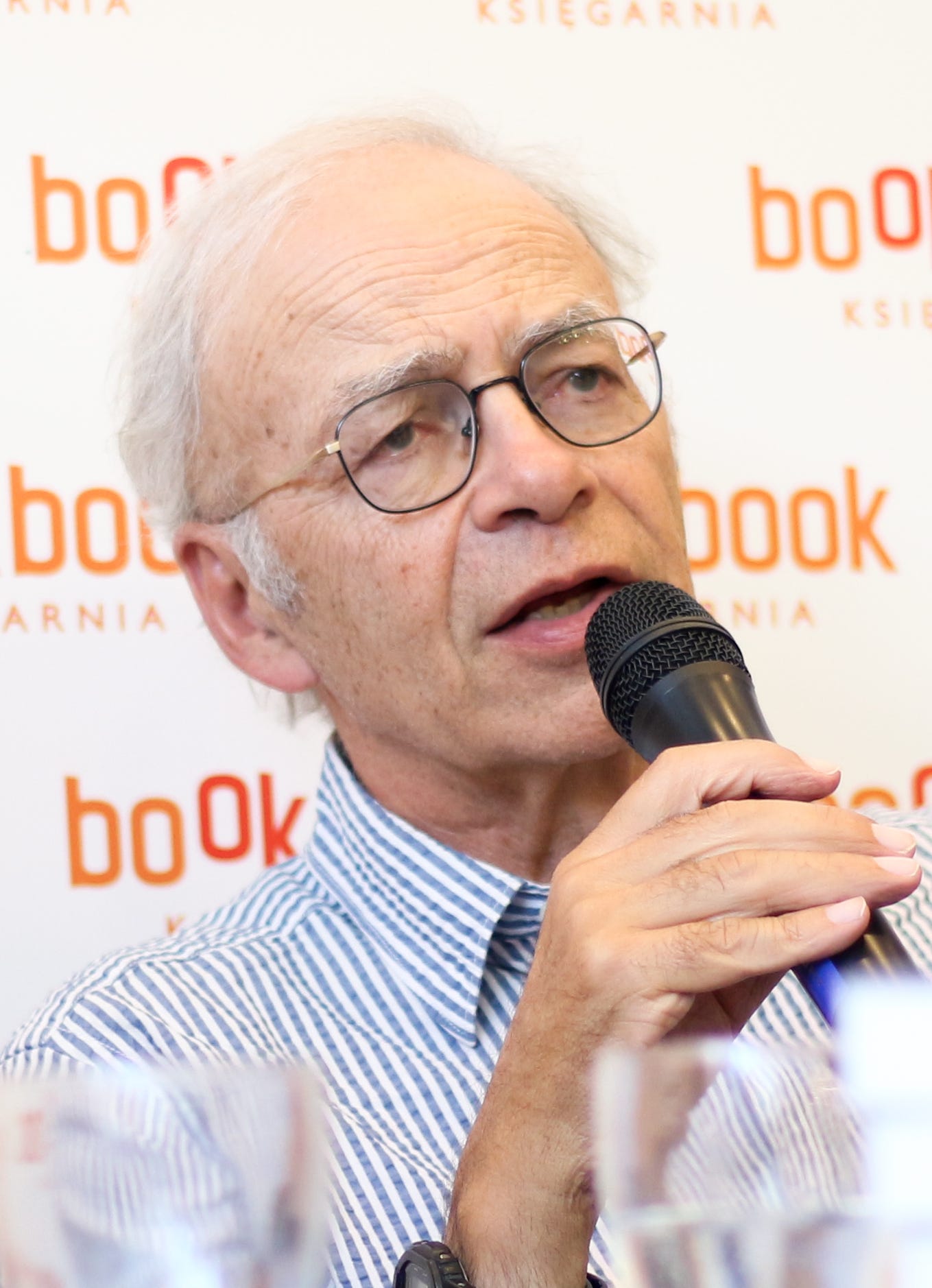

The man’s name is Peter Singer and the title of his paper is Famine, Affluence, and Morality. Here he is:

Image: Australian philosopher Peter Singer, pictured in 2017. By Ula Zarosa - IMG_5658, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php

He is, of course, foolish. Man cannot live by bread alone, and needs an occasional spoonful of caviar to render it more palatable. But, it is not in that that Singer is foolish, for he mentions neither in his paper. Where he errs into folly is in his title: the word morality is found there, and it immediately gets people’s backs up. Either because people misunderstand what morality is, could be or is intended by Singer to be; or because his morality isn’t theirs, and he has no idea at all, and should not be preaching to them — which, also incidentally, he doesn’t; or because morality is a nebulous concept and Singer uses it to tempt the unsuspecting rich and poor public, alike, into committing acts of gross idiocy, which they could end up ruing to the end of their born days. That last part is, actually, true. But that’s got nothing to do with morality, rather with injudiciousness.

Singer’s paper is not complicated. I’ll put it in a nutshell, and then you can go and read the full Monty, or watch vids reciting its text on YouTube, explaining its text, and even his detractors. In essence, therefore, this is what he writes:

A boy is drowning in a park, in a pond. You happen to notice his plight as you pass through the park. Others, too, have noticed and are concerned. But, concerned as everyone is, no one is attempting a rescue. Fact is, a drowning boy is gone in 30 to 60 seconds: if anyone is to act to save his life, it must be done now.

Would you attempt a rescue? Let’s assume you can swim, like a fish. You’re wearing your best tweeds, however. They will be spoiled, and your shoes: crocodile. Would you take the time to tear off your clothes? The seconds are ticking. Well: will you go, or will you let him drown and continue on your way?

It’s an everyday dilemma that nonetheless doesn’t occur to all of us every day, but it is conceivable. There is a plight menacing another that you are in a perfect position to succour to, and which requires an instant answer, but not without minor inconvenience. Do you act? Or do you “pass by on the other side”?

Whether you would act or not, with this example, Singer hopes to conjure in the mind a situation that his readers would agree is, what he calls, a very bad thing. Very bad things include death, starvation, hunger, suffering. Singer argues that, while wealthy western societies may not have the physical means to alleviate suffering endured in far-off places, due to events like famine and hunger, they do have means within easy reach by which the condition of those who suffer can be at least alleviated.

When we generally agree that saving the boy is the right thing to do, a laudable thing, an entirely conscionable thing, but baulk at deploying our means to actually saving him, we are, to that extent, passers-by on the other side, and not St Luke’s Good Samaritan. In a case of monetary donation to a charity, the inconvenience, comparable to wetting our clothes in the drowning boy example, becomes our attendant deprivation of benefit, which we would otherwise have from spending our money on ourselves. According to Plato, if we conceived of giving to charity as being a use of our funds that serves the justice of the boy’s case, and we acted, we would in fact be deprived of nothing. Plato contended that those who wreak injustice suffer more from their own injustice than those on whom injustice is heaped. To complete this literary round, Shakespeare might have called that “hoist with his own petar.”1

If we decide to keep our money for ourselves, and that money is excess and not required to cover our necessary living expenses, then it becomes dedicated to what Singer identifies as luxury, which is outlays made by a person which are not essential to his or her survival (survival including things like making future provision and paying into pensions and making a nest egg for a rainy day). Anything over and above that, which we decide to spend on more lavish outlays, like expensive foreign holidays or a fancy car or dining out with fine wine and exotic food, is luxury; and it represents the equivalent benefit that flows to the individual when they make a positive decision not, instead, to donate the money to relieving the deadly situation affecting those in famine areas.

Singer’s conclusion is that any funds an individual holds that are over and above his reasonable and necessary expenses should be given to charity because failure to do that constitutes immorality. It is like seeing someone drown and knowing that you could save them and deciding nonetheless to pass on by. He equates the immorality of failure to lift a finger to help another’s physical plight to the immorality of failing to issue a cheque.

It is a very extreme position, and it’s one that initially has shock value. It is a situation with moral aspects, physical aspects and philosophical aspects; and the philosophy doesn’t stop with the moral dilemma that plays itself out in the individual’s head. One could ask oneself why you should feel morally bound to do anything for or on anybody’s behalf that is not squarely within your duty under the law. That is a fair point but, defining one’s moral bounds as being those which are not otherwise ring-fenced by the law evades the distinction that jurisprudence draws between what is the law, failure to abide by which will result in a legal penalty, and that which is not enshrined in law but is a creature of the moral conscience, failure to abide by which will result in no legal penalty, but may result in social censure, if not God’s.

Over and above this is the notion that the funds at anyone’s disposal are theirs, and theirs alone, by simple dint of the fact that it was they who worked for them. They put in the effort, they obtained the degree, they invested in the trade or practice which garnered them the profits that these funds represent, and should it not then be entirely within their own discretion as to where the funds should be applied? Of course, it should, but it is a constant that the financial standing of an individual is not automatically and necessarily a reflection of the personal effort that he or she invested in generating it.

The First Nations of North America and other parts of the world live by a homespun philosophy that says they should take from the land what they need, and nothing more; and should return to the land what they can, and nothing less. By their measure, anyone who takes from the land, and who thereby reaps a reward or a benefit that goes beyond their need, is by definition greedy and, what is more, appropriates a resource that not only exceeds their needs but deprives others within their community of that resource to fulfil their own needs. Those who do not belong to First Nation tribes live far more by a philosophy of finders keepers, strike while the iron is hot and fortune favours the bold (especially when they are armed with a rifle).

These latter considerations are not broached by Singer in his paper, but I don’t think they can be discounted in toto. Nevertheless, Singer’s is a philosophy that is radical and any consideration of it can usefully be discussed in conversation, on its merits and any demerits that it possesses. This has been difficult for me given that I live on my own. However, I saw a recording of the Singer paper on YouTube and was interested by some of the questions and comments that followed and have responded to them and wanted to share this with you. If you are interested, you yourself may peruse them and, if there are any points on which you would like to engage with me, then there are comment boxes below, where you may do so.

For each response thread, the correspondent’s comment is indicated in italics (suitably edited) and my response, likewise, in the form of an outlined quote. You might call it the Socratic method.

Jane

Did Mr Singer donate some or all of the profits from the sale of this book? Did he practise what he preached? Mr Singer seems to have overlooked the fact that those whom we entrust with the power to control the money we donate are less than honest in their handling of said funds.

The fact that these famines are man-made makes it a very real possibility that they will be or are created to transfer wealth, to those creating the famine, by intercepting the monies that should have gone to those in need. Mr Singer’s perception is very limited.

The whole point of organised charities was to try and achieve what Mr Singer suggests, to gather enough money at one time and teach men to fish as well as feeding them for the days until they learn enough about fishing to no longer need to be fed daily. But corruption has sidelined the long-term goals of teaching people the skills to live independently of charity. Many people collect exorbitant paychecks to “manage” the money, creating positions of employment for relatives, insane expense accounts, etc.

Fix all of those problems before passing moral judgement on how non-charitable people supposedly are!

Your first question caught my eye, Jane. And the answer is: yes. Since he published his paper, Mr Singer has given regularly and handsomely to charity, every penny that is beyond his reasonable needs. He practises what he preaches, no question. He does not advocate that people should reduce themselves to penury, but that they think twice before indulging in luxury. It mostly falls on deaf ears, but some do take note. I am one.

Corruption is an ever-present issue. In 1894, W. T. Stead wrote Satan’s Invisible World Displayed or, Despairing Democracy: A Study of Greater New York, in which he detailed how New York had been defrauded by members of the Tammany Society of over $160 million (that’s the amount at the time, not now; according to www.measuringworth.com, the current value is between $31 and 60 billion). It’s not a problem of today but of all times, and is so endemic as to tempt the conclusion that it’s not a problem, it’s a fact of life.

If I give protection money to the mafia, do I feed corruption? Yes, but I keep my store from being fire-bombed. I pay commission to an insurance agent, in order to get insurance: you might say that I pay a fraudster to get a fraudster for me. So, should we eschew every effort made to better the human condition because it benefits a middleman? Maybe. It’s a view, but only if you know where all the middlemen are who take a slice of what you transact. And, they’re everywhere.

Corruption is a major stumbling block to development in Africa. There, the elite, who attain political clout, invariably use it to enrich themselves. I asked an expert once why The Gambia and Senegal abandoned their moves to unite in the 1980s. He replied, “Two countries can have two presidents.”

Zimbabwe makes a fortune on exporting gold, which it never mined. It’s a money-laundering operation that reaps millions for criminals, including the president of Zimbabwe (see the Al Jazeera YouTube channel and its Gold Mafia series). Should I therefore make a point of never donating to a cause that includes Zimbabwe as its beneficiaries?

In clean countries, public services are offered by the government, for which taxes are paid. That means that, if I don’t want a particular service, I still need to pay the taxes that go to providing it. It’s called a social contract. But, in other countries, public services can only be accessed by paying a facilitation fee (a meeting with Zimbabwe’s president costs $200,000, for instance, at least according to Al Jazeera). If you’re sure you need the service, then you pay the facilitation fee, but it effectively means that only those who do need it will pay the fee for it. No one else does. Corruption can be an efficient means to ensure only those who receive a service need to pay for it.

It would be nice to think that things are that well regulated, but, of course, they’re not. Because everyone pays taxes, like it or not.

Dan

What Singer proposes is quite extreme and unrealistic for the majority of people. He doesn’t take all other variables into consideration, as if morality were, by far, the most essential pillar in human existence.

Also, if all people did this, we would be living in a highly dysfunctional society, as people would constantly base their lives around giving what they have in excess. Rich people, by giving away, would become poor compared to the people they’re helping, while poor people would become rich in comparison and would need to take the same approach in the cycle.

Morality would almost completely replace the idea of money, which I think would transform it eventually into something similar to religion throughout history. Such excess of morality will make it lose its essence and turn it into the most egotistical behaviour you can get.

I understand the point Singer makes, but it cannot be stated that it would produce a better outcome for humanity. It is too simplistic and extreme, and what we need are more balanced approaches.

Agreed, it is quite extreme. But it’s not unrealistic: remember, what Singer advocates is not absolute; it is relative to him or her who decides to undertake the philosophy. It’s not a set of hard rules, it is an exhortation: simply to think twice before indulging in luxury.

So, if I believe that I have £100 spare each month, which is not otherwise allocated to my current and foreseeable future needs, the education of my children and possible rises in the price of petrol or food, then the question for me is: what to do with the £100? I can save it, invest it, buy a trinket, or I can give it. The choice rests on my morality, not yours, and not anyone else’s, Dan. The £100 is lawfully mine and I may lawfully decide which option to choose. As may you. As may everyone.

Dramatist Edward Bond wrote once (in A Short Book for Troubled Times) about airmen who drop bombs on enemy countries and return to their families to be embraced by their own children, whereas they’ve just bombed other people’s children to hell. “How can they live with themselves?” he asks. Well, they live with themselves because they are able to invent a morality that suits them. Perhaps several moralities. Moralities are cheap, and malleable, dispensable even, like fashion clothing. Except that, when they get altered to suit circumstances or dropped due to their inconvenience, they are no longer like fashion clothing; instead they are fashion clothing — this season’s.

Morality is not the product of being told what to do; it is the product of an intense conversation that an individual engages in with his or her own conscience. When the conscience tells you not to care about others, then that is your morality, and no one can take that away from you. Only you can.

Singer takes conceivable situations and translates them into what he believes would be commonly held emotions. Clearly, he selects his examples carefully, so as to reach a common denominator that he reasonably thinks will be shared by most, if not all, of his readers (but, he will miss his mark with some folk, inevitably). From his examples, he extrapolates a general sense of right, which he calls morality, but which is individual to each of us. And, from that, he exhorts us to act appropriately, in line with the morality that we have concluded is ours.

Your dysfunctionality argument attracts me. I do wonder, however, whether it will ever be put to the test.

Thank you for your in-depth explanation, you presented some interesting points. Still, I think it’s unrealistic for most people for long periods of time. I don’t see many adopting this as a life philosophy and romanticizing the idea of morality this way.

Where I believe Singer was wrong is that he tried using the same tools to create a different system. His way of thinking will never make an impactful change, because the tools being used are too shallow for the individual and collective consciousness.

I’ll tell you how I would constantly give away some of my hard-earned: I need to know exactly what happens with it. What was bought with it, down to the last penny. What family/people benefited from it and what is their full name? What is their financial situation and what are their opportunities in terms of work and education? How do they take advantage of these opportunities, if any? Where can I invest a % of that money to create opportunities, if there are none? How can these opportunities be directly linked to the people I’m helping? How can we set up a way for us to communicate with each other, if there’s none? As well as many other approaches that would create a direct connection between me and the people I’m helping.

I would pay separately for this system to be set up, just like you pay the fees for using an investing platform. Even if I paid 25% of that money for such system to be set up, I bet it would be much more effective in helping people. If I create within myself the belief of a long-term close relationship with the people I’m helping, chances are I won’t give up on them. I don’t want to just give money to an external entity that creates a link between me and people I will never know anything about. You might get a few dollars out of me each month, if you’re lucky, but that’s about it.

As an individual, I need within myself the rightly balanced illusion between selfishness and selflessness. I want to help create opportunities for people in need, just like I did for myself my whole life, or for my children’s future. At the same time, treat me like a pawn with my money, regardless of what you say you represent, and you won’t get far with me.

Dan, I would like to also thank you for coming back in such good detail and with so many constructive ideas and, when I read these, I can assure you that you and I are singing from the same hymn sheet.

I myself know a family in The Gambia, a country in western Africa. I met this chap on a business-people’s website and we clicked, exchanged views in our posts and got to know each other. I never offered and he never asked for money and our exchanges concentrated mainly on possibilities for getting work in The Gambia.

However, the point arose when his sister was very sick at home, suffering from malaria: it’s a very common disease in Africa and not everyone there can afford the precautions against getting it and not many can afford the cure medication. He fielded a request with nothing more than that: was there anything I could do to help?

The question arose in my mind: was I being scammed? When I went to a payment agency to make a modest payment of 100 euros to him, I was just at the point of pressing “approved” when there flashed onto the screen a warning about being sure it wasn’t a scam. I hesitated and, for a while, didn’t really know what to do.

Thing was that I trusted the man and yet it seems that scams are all too common: how could I be sure? I asked a contact of mine in Asia and he put me onto a website which is called baluwo.com which, on your behalf, will provide groceries, telephone call credit or pay an electric bill or organise construction materials on your behalf: you pay them and they will provide the services or the goods to the people in question. It’s often used by expatriate Africans to send money home to their families, but who don’t want to go through the rigmarole of using a bank transfer (but it’s not a money transfer: you in fact pay for something that they can use). I suggested this to my contact in The Gambia and he was delighted. I ended up spending 134 euros.

The family in The Gambia were profuse in their thanks and gratitude: it’s a satisfactory solution for me and them, because they were then able to allocate funds to get medication for their ill relative. I’m not tremendously well off myself and I don’t have that much to spare but, every now and then, I’m able to make a small contribution to these people, whom I know.

I get nothing in return, except for thanks. However you really need to know who you are going to be making such a transfer to, so how do you come into contact with the needy? My contact was by chance, but I don’t think that you would have difficulty in ascertaining who you might sponsor. It seems very direct and in fact limited: I always ask the family to spread kindness, and to help those who are around them, the way I have helped them: that way some kind of fellowship can be created. But I can’t control that, I don’t really want to either.

I don’t feel particularly good about myself so doing it but I’m happy that, in some small way, I’m able to make some difference. You seem so full of determination: I’m sure that you will find your way too, to make a difference.

Duff

This is a bad way to approach the problem. Starting off with East Bengal of all places, where Churchill himself created a famine. It’s the approach of a privileged white man who has never confronted a structure of power and carries the cultural baggage of self defeating individualism.

I like your comment: not because I think you’re right in where you go with it, but because it provokes thought. I like Singer, but am I indulging in self-defeating individualism as a result?

Mr Singer is white, and he may be privileged, I don’t know. But he is exhorting privileged, white men, amongst others, to think differently about their duty to unprivileged, non-white men, and I think that should garner praise more than condemnation, don’t you? In fact, I think Singer’s philosophy is better received precisely because he asks his own sort to change their ways, rather than the request coming from the beneficiaries themselves.

Churchill is dead. He was great. He was dreadful. He was a politician. He was.

Others are. Others are living and need help. We cannot refuse help to the living on the basis of the greatness, or dreadfulness, or whatever, of a man who died 60 years ago. If anything, if he had failings, that’s all the more reason to make up for them. Todays’ politicians also have their failings — should the world then abandon the people whom these politicians fail? If that were so, I fear that we would offer help to nobody, for all politicians fail in one way or another. That’s perhaps why people need help.

I disagree that Singer is thinking differently about charity. We see it everywhere, that charity is good and that we can make a difference. The TV adverts, the donation jars at the grocery store, etc. Corporations and governments adopt this position mostly to wash their hands of the need to offer any systemic change so they can continue their robbery of the third world and blame us for it.

I think it’s the first time I ever heard “Singer is not thinking differently about charity.” I won’t deny that it is a good thing to be aware of the full consequences of what we do. So, don’t fly, because the pollution it creates makes airlines rich, and the rich are doing untold damage to justice by greasing the palms of Clarence Thomas, which is playing into the hands of right-wing extremists, and etc. etc. If I knew every last consequence of every last breath I take, then my wisdom would be without end.

I don’t intend to be cynical but, perhaps you’re different to me, maybe you are far more circumspect about the chain reactions that permeate and criss-cross the globe. I’m not trying to be funny, and I don’t want any arguments. But you seem to say that if everyone gave to charity as Singer advocates, the governments that we elect to office would simply wrap up any notion of international aid that they currently engage in, and the givers of money to charity would be lambasted by the Third World for causing them a sharp decline in their living standards. I think that’s the causal chain you identify, yes?

The US’s GDP is $26.14 trillion at the present time. The US donates aid (it’s hard to quantify, especially in terms of lent manpower and military training and such like, but in pure money terms) in an amount of $49 billion. A trillion is 12 zeros, and a billion is nine. So, cancelling a few zeros for comprehensibility’s sake: the US earns in one year $2,614.00, of which it spends in total aid, all countries, all agencies included: $4.90. In percentage terms, that is 0.187%.

Take-home pay in the US varies from state to state, but is at around $40,000 after tax (as free, disposable income). If each wage-earner in the US donated 0.187% of that take-home pay to charity, they would be donating annually a sum of $74.98. Your posit suggests that working Americans do not have funds in excess of $75 that they spend on luxuries in a year. I don’t know what people spend their money on, but I think I can safely venture a guess that their spending on luxuries, over and beyond their necessities, is way beyond $75 a year and is probably more like $75 a week.

But that is not your issue. Your issue is that if the Americans and everyone else on the wealthy side of the globe gave $75 or more to charity, then, as a result of that, the US and every other government in the world would, at a stroke, abrogate their responsibilities for international aid, thus plummeting the third world into bottomless penury, for which you believe a finger would be pointed at you, among others.

First, there would be no penury in the third world: there would be boundless rejoicing. Because, by exceeding the figure of $74.98, no one would need international aid. And, supposing I’m right and people donated not $75 a year but per week, then the amount of charity flowing to the third world would multiply by a factor of 52. In real terms, instead of the US spending $49 billion, it would spend $2.55 trillion. In one year, a single country’s population, the US’s, could wipe out poverty.

But, and it is a MEGA-but, you are right in one thing: actions do have consequences. And aid has consequences as well. Because much of it never gets to where it’s intended. It is purloined, stolen, embezzled, thieved; and most of that is done by the very people into whose hands it is entrusted and who have stated a case to receive it in the first place — they are the governments, administrators and even presidents of Africa’s ailing third world. UNICEF puts to work 20% of what is donated to it, with 80% going on administration; and that’s before it seeps into the back-hands of officials, of administrators, of people who collect 200 sacks of rice and deliver 150.

The government of Uganda, which languishes low down the transparency index, at place 142 (joint), is a member of the United Nations, which states in its charter that its purpose includes “to reaffirm faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person, in the equal rights of men and women”. Uganda joined the UN, thus subscribing to that charter, in 1962 and has been party to the Vienna Declaration, and to the institution of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Uganda has also just enacted legislation by which homosexuals can be sentenced to death: for being gay. Persons who flee Uganda because of persecution for their orientation may seek refuge at Kakuma, a UNHCR camp in Kenya, with a population of 300,000. But, anyone wanting resettlement out of Kakuma, a purpose enshrined in the charter by which the UNHCR was created and which is its very aim and object, must pay a bribe to the UN official at the camp who offers them a new life in, say, Canada, or the US, or wherever. Seventy thousand shillings, which is around $517.18. That’s how public services are administered there: by paying bribes.

Duff, do you take a view that, because corruption and bribery are rife in Africa, we should not help those who get nothing but the basic framework of what aid is intended to procure, without ever solving the issues? Just leave the corrupt officials to take their slice of the action, and leave the people hungry and hopeless?

Besides, no country is ever going to stop making grants of aid to the third world. Not even if we all gave it 75 bucks a week. Because aid is not just intended and designed for the poor. So, who else is it for?

It’s for the very people who receive it now: it’s for the rich. It goes, at least in part, to the rich in Africa and it’s a bribe: to ask them not to incite revolution against our industries or rise up in a war against their neighbours and cause us difficulties or partner up with Russia or China. We, the west, the old and new worlds, pay aid to them, the third world, in order to keep the peace, so that they can get rich, and then kindly leave office, so that someone else gets a turn a being rich for a while, thus making it look as if they have democracy there.

The only good thing I can say against this and for charity is that, at least, charity gets the help that’s needed more directly to those who need it; but there is much more that makes Africa poor than just poverty.

The laws against homosexuality are put there, not because the governments are anti-gay but because, whilst they steal money from their own people, they use the quasi-religious fervour behind persecution of gays, including turning a blind eye to them being lynched, in order to unite their people in one voice, singing in so loud a throng that they quite forget they’re being fleeced by their own leaders. These laws a but distraction, like a conjuror would use.

The Outcast

I hear time and time again morality being used as the guidestone to what is wrong and right, what we should and shouldn’t do. This is a very narrow view of morality.

There is no objective morality; it is purely subjective: for example, different religious groups will have a different perspective on what is right and wrong. All we can objectively say is that there is a social agreement on how to behave and what is expected from each individual. Therefore saving anyone is a subjective reality, and what is considered socially acceptable.

The home truth is that a majority of people will live their lives in selfish ignorance, which is supported and rewarded by society as a whole. Society teaches us: to have more is better, materialism trumps life.

It is now the individual who must decide what their morality dictates and whether to align themselves with objective social norms or perhaps take a more empathetic approach.

Yes. Except, it is not now the individual who must decide. It has always been that way.

Morality is the set of rules that each individual formulates for him or herself that is outside the remit of the law. The law tells you what to do and not do and imposes penalties for failure to obey. Morality tells you the same, but imposes no legal sanction for failure to obey, not from outside. The sanction comes from you yourself: guilt. No guilt, no sanction. But no other party is involved. Morality is imposed by the self on the self.

There is an area in which the two cross: the law against murder will generally match the human psyche’s aversion to taking another’s life. Theft is more nuanced in some cases: stealing from the poor would be viewed as reprehensible; stealing from a rich man less so. Both are stealing. (In fact, one could extrapolate Singer’s ideas and say that spending money on luxury is equivalent to stealing from the poor, but I don’t want to complicate things.)

Lastly, there are laws that have no bearing on morality, or not on the individual’s morality, in any case. Taxation is a part of the law that knows no “natural justice”: it can be argued that it provides social services and therefore does have a moral basis, but it provides for lots of things for which there is no moral basis, but rather an economic basis.

But, take the case of bankruptcy laws: what is the moral basis for excusing someone their debts because they were profligate? In Belgium, bankruptcy was until recently a procedure that could not be applied to individuals, only to companies. So, if I practised a trade as a sole trader, I would be liable for my debts my life long, and my estate afterwards. If I incorporated a limited company, it could be bankrupted and my creditors would then not be paid. That was the law (it was changed in the 1990s).

So, morality has a role to play, over and above the law. However, the law is where some people’s morality stops; and, for some, it stops even within the remit of the law, but that’s another matter.

I find your comment insightful for someone who deploys the Guy Fawkes mask as an avatar. Thank you.

Marc

People are ethnocentric. They will help those within their ethnos. Starting with their children.

Ethnic groups are, at best, competing with each other and, at worst, openly hostile to each other. So, why would an ethic group help a competitor? Trying to remove people’s ethic preference is very arbitrary. Why just save people? Why not save all mammals or all living entities?

I do agree that limiting suffering is a good goal. But this can only work within each ethic group.

I agree, up to a point. I knew racists in my youth (yes, probably even now: I’m white) who had black friends. I think it’s easier to be a racist or to hate an ethnic group when you don’t know them. And even to love them: we romanticise them, absent hard, annoying habits.

It helps if one has a friend in another ethnic group (especially if you’re “introduced”) to be more accepting and less hostile; but, as long as they are “faceless”, it’s easier to deal with them as a commodity. The same way that cold callers tell you their name: it’s easier to hang up on someone whose name you don’t know.

Some complained when sympathy was expressed to Ukraine by Europeans that we’d had little sympathy for Syria etc. Your point says it quite succinctly: the Middle East will care for Syrians; for Ukrainians, there are Europeans. They’re more “us”, more relatable-to. There’s much in what you say.

Can one really relate “globally” though? I smile: I think you’d be surprised.

I’ve expended a great deal of energy is trying to persuade others why I should have the freedom to impoverish myself by caring for others. Perhaps you will find the exercise a futile one. And perhaps, you, too, will give a pound next flag day. Whether you do or don’t, your decision will be yours. Singer’s decision to write down his strong notions about his duty to mankind changed him.

And it is changing me.

Addendum:

What is luxury?

Luxury is immoral, says Singer.

Luxury is selfish greed, say the First Nations of North America. (I analyse greed, for its part, as follows (We want freedom and fear slavery):

Greed means three very different things in three very different contexts, which differ but in their degree of repugnance. First is the concept as applied by First Nation peoples, typically in North America or Australia. They live by a simple mantra: to take from the land what they need, and nothing more; and to return to the land what they are able to, and nothing less. In this, argument arises simply based on one man professing a greater need than another. Need is not something that is controlled and measured; it’s felt, and every one of us knows what we need and what we don’t; we eternally measure ourselves against a standard that we ourselves have designed, and feign surprise when we fit it: we designed it.

In Molière’s play The Miser (L’Avare), the central character, Harpagon, amuses the other characters and the audience with his ridiculous means for preserving his fortune. His fortune came from lending money at usurious rates of interest, but he goes to great comic lengths to preserve it. Yet, Molière does paint his character as having one virtue, if no other: at no point during his play does Molière contrive to have Harpagon covet property, money or any possession that is rightfully the property of another person — he’s no thief. His concerns are limited simply to preserving his own fortune, but don’t extend to acquiring the fortunes of others.

The third, and by far the worst, degree of greed is that which is manifested by the banking system and the stock market. They turn not a hair at the prospect of bankrupting those who do business with them, in the interests of acquiring their property, sequestered as legally theirs by virtue of debt or some contractual meeting of the minds: the law’s guarantee of protection for lenders has made devices that procure insolvency and the glut of the windfall. If ever a ploughshare was turned into a sword.

Luxury is unearned privilege, say communists.

Luxury is the product of hard work and dedication, say capitalists.

And, luxury, say I, is evil. Not because it intentionally procures harm to others. But, rather, because intentionally procuring harm to others is not, contrary to common conceptions, what evil is. From this article:

God’s law requires you to love your neighbour as you would love yourself. Now, at the very least, that would mean that, if you take giving to charity as a measure of your godliness, then you should give half your possessions to charity, because the half you give — love for others — would match the half you retain — love for yourself. But very few do even that. We generally retain far more of our possessions for ourselves than we give to charity, which means that, on that score, if score it is that we want to keep, a divestment of half your possessions would only give you a score draw in the God v. Devil league championship; and keeping more for yourself than you give to charity means the Devil wins that game on a penalty shootout.

Because God’s law is to love others, and Satan’s law is to love thyself. It does not, as we conveniently define satanism, mean “do harm to others”, so that — and this is the convenience part — no one who gives only £5 to charity would consider themselves as doing harm to anyone (other than their own purse), and they cannot thereby be evil, or so they reason. It’s this equating evil with doing harm to others that gets us most confused in determining where we are in the God/Devil league table, and it is part of why we see God as responsible for failing to prevent disasters. You see, God and the Devil, in prevailing upon our consciences, don’t look at what we do on this Earth; rather, in a reverse logic to the statutory offence, they look only at what we intend. It is our intentions that nourish or deteriorate our souls, and not our acts. And it is the net goodness or evilness of our intentions that determines the state of our souls.

William Shakespeare: The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, Act III, scene 4 (Hamlet speaks):

There’s letters seal’d, and my two schoolfellows,

Whom I will trust as I will adders fang’d,

They bear the mandate, they must sweep my way

And marshal me to knavery. Let it work,

For ’tis the sport to have the enginer

Hoist with his own petar, an’t shall go hard

But I will delve one yard below their mines,

And blow them at the moon.