Into Africa

The moral dilemma surrounding colonial moral education

Happy new year. This post is dedicated to Abs Ngum, whom you can find, if you look, on LinkedIn at https://www.linkedin.com/in/abs-ngum-544547237/. Some of you perhaps already know Abs through my columns here. He is not like most of us here. He is Black. He is African. He is poor. No, he is not poor. He is dirt poor, if poor means having no money. And he is rich, if rich means having a wholesome outlook on life. He would like to leave his home country, which he struggles in. He and his six brothers and sisters and his mother. His brother made out for Libya a year ago, and crossed the Sahara desert on foot, was attacked and left for dead. He lost his shoes, he lost everything. In the end, the United Nations repatriated him back home, to the bosom of his family. I would have been terrified to embark on such a journey. But I am not—yet—desperate enough to undertake a quest like that. I am lucky.

Jojo and the family lost their home recently. The rent on their shack was 35 euros a year, and they could not afford it, so they were evicted. But Abs is no immigrant. He is not one of those whom the far right want to set alight. He has not come to live in a ramshackle hotel in Clacton-on-Sea. He is in the place he was born, in The Gambia. His mother, Jojo, is from Kunta Kinteh island, in the estuary of the River Gambia. It is there they have their roots, and it is there where they live in penury.

When Rudyard Kipling would defy colonial rules and wander alone through downtown Lucknow in the evenings, he shocked not only his British comrades, but also the Indian natives. He did not belong there. And the Indian natives did not belong up on the hill. They keep themselves apart from each other. Like they keep themselves apart in many other places. Kipling wanted to learn about the indigenous people of India, however. And I want to learn about those of Africa.

I have never been to Africa, except for a one-hour stop-over at Monastir airport, in Tunisia. But Abs has often said I should come and visit, and I feel a need to do that; but the usual: no resources. So, we write to each other and offer each other good wishes and fortitude. Perhaps you could navigate to his LinkedIn profile and wish him your kind wishes as well.

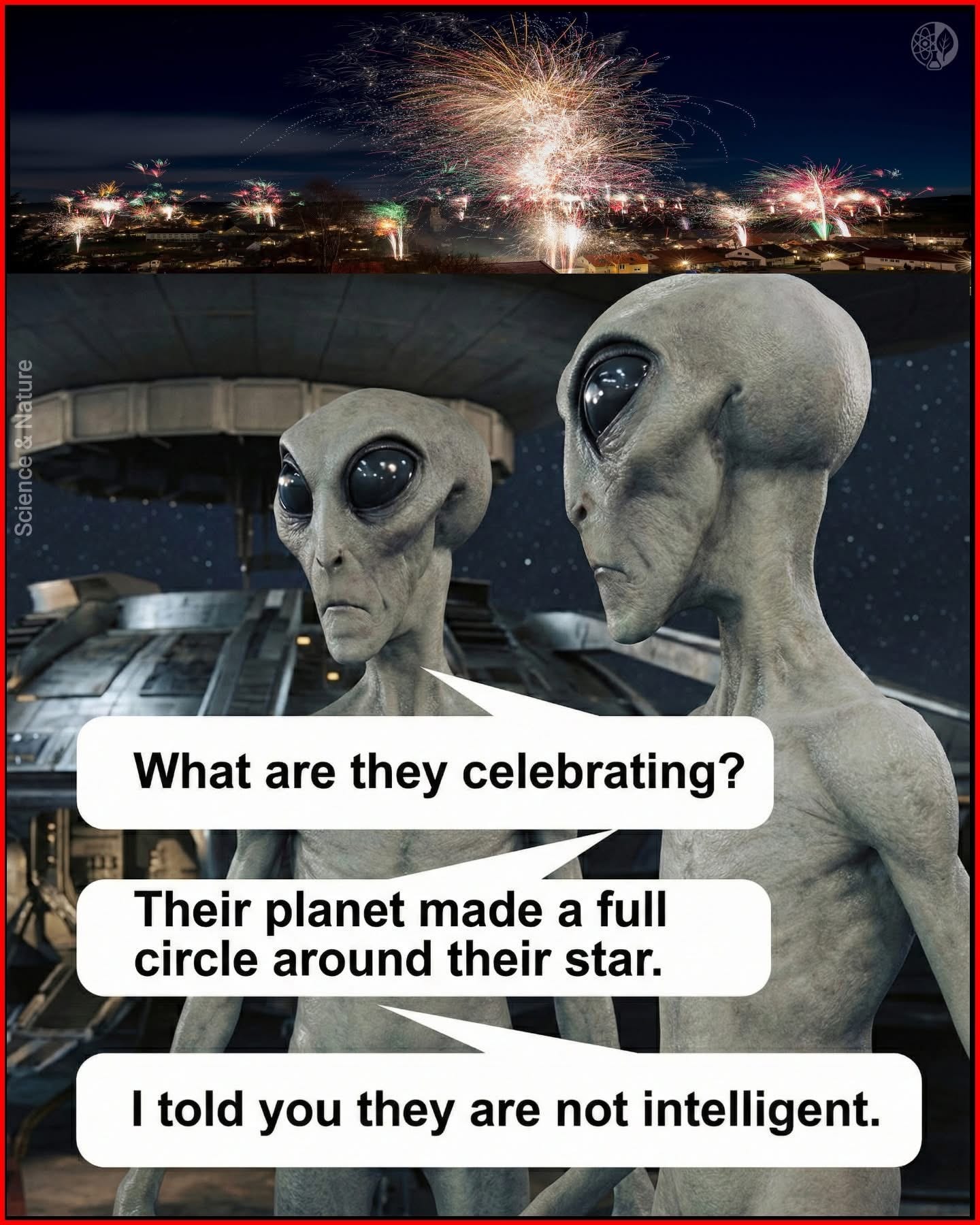

I was just at the post office in our village, to send off a happy new year card to a friend in Italy. It has a picture of Big Ben at the 12 o’clock hour, and celebratory champagne glasses and starbursts. It is all about happiness at new year. Meanwhile, my house mate showed me a cartoon of two extra-terrestrials observing new year fireworks. “What are they celebrating?” asks one. The other replies, “Their planet made a full circle around their star.” The first retorts, “I told you they are not intelligent.”

As with all jokes that are funny, the joke is funny. But, like all good jokes, it holds a deeper truth.

First, do we celebrate the conclusion of a successful circumnavigation of our star, or do we wish each other happiness for the future circumnavigation, which we have now but embarked upon? Do we reflect on the year past, and evaluate how we might make the coming year better and, if we do, is that better for us, for our entourage, or our world? Is happy new year a greeting we broadcast to all mankind, or is it intended selectively, just as happy birthday is intended for those whose birthday it is?

We don’t say happy new year in Belgium. We say best wishes (beste wensen, meilleurs voeux). I think that that sounds more honest: because however happy we may wish our fellow Earthlings to be in their new year, it’s as blindingly optimistic as it is pessimistic to wish someone who’s going on a sea voyage I hope you don’t drown. But, still we love platitudes, because they fill in the gaps in conversations and make us look social, whilst all we’re doing is trying to impress. Sort-of setting off a verbal firework.

What confirms me in this dour spirit is that I know for a fact that, across the world, governments are planning with conscious intent to make other people’s 2026s as unhappy as they can. It makes me wonder how they can possibly utter the words happy new year with anything like half-human sincerity. It is not celebrating a rotation around the sun that makes us look unintelligent. It is that blithe way in which we treat each other.

In the 1985 film Out of Africa, which is about the loveless marriage between Karen Blixen and Bror von Blixen-Finecke, and the marriageless love between Karen Blixen and Denys Finch Hutton, in Kenya during the time of the First World War, intelligence plays a role. In her attempts to seek rapprochement with the native Kenyans, which were largely successful, Karen Blixen sets up a school for the children of the local tribe. With a machete strike against one of the school’s supporting columns, the chief of the tribe indicates a height, above which no child could enter the school, which shocked Karen. Children above that height were required to work, he said, not to learn reading and writing.

Finch Hutton expresses his disapproval of the school. Although very much part of the expat community, as we might kindly designate colonialists in that age, he had a sense of empathy with Africa and its people that many colonial masters lacked (“The bloody w*gs can’t even count their sheep!” one Brit exclaims to Blixen when learning of the school, which earns him a reprimand from Blixen’s escort and a slap across the face from her). More colonialists should have been slapped across the face, in my humble view. Still, Finch Hutton himself was against the school, set up to educate the Black children.

When I was in Germany in 1990, and its two halves were coming together again, a West German lawyer of my acquaintance came out with a phrase I have never forgotten: “Sie müssen erzogen werden”: the Easterners need to be educated. I was shocked at the implication that Wessies had nothing whatsoever to learn from Ossies. Except turning right on a red light.

Finch Hutton had no great problem with indigenous Kenyans learning to cope in the modern, 20th century world by being able to read and write. What he objected to was how it was being formulated: almost as if the Blacks of Kenya should all become little Eton schoolboys. “They were educated before we came,” he said, “Just differently. But it met their needs exactly.”

Karen Blixen finally quit Africa after Finch Hutton’s death in an aeroplane accident, and Isak Dinesen wrote her story, on which Sydney Pollack’s film was (loosely) based. Both it and the film bore as their title Out of Africa. It’s three little words, which form a mantle of a multiplicity of stories, of colonial cruelty, of facile war, of senseless killings, of hopeless farms growing the wrong crop in the wrong place, and of hopeless loves seeking nurture, in the wrong place. Kenya was wrenched from its peoples and imbued with a moral code, invented by plutocratic Brits to show the world how bloody deserving they were to rule it: it was they who imposed the 1897 amendments to the Penal Code of British East Africa, which remain in force to this day, and give just cause for modern Africans to question why it is that today’s Africa clings so dearly to a criminal justice system that was foisted upon them by a perfidious overseer.

At the time of Karen Blixen, there was a common cocktail party enquiry that did the rounds in White society: Are you married, or are you going to Kenya? The clear implication was that being married in Kenya was no bar to jumping into bed with anyone, be they man or woman. The moral standard that the British imported into East Africa was reserved, naturally, for anyone but the colonialist himself (I use the masculine advisedly). Moral teaching was for the … what was the expression? Ah, yes: bloody ****. But white men, and implicitly, white women at the men’s behest, were freed from all and any moral strictures in their relations inter se. For Blixen, the result was syphilis, contracted from the husband with whom she had previously contracted their lawful marriage.

It’s a pattern we see mirrored even today, in the high moral stance assumed in terms of the United Nations Charter, and flouted flagrantly by the parties bound under it but whom it was never intended to bind, don’t be so silly. It was only ever meant for … (see above, I can’t bring myself to type it again, even with an asterisk).

It is only right that gay rights and Africa should be a subject at this time of year. As gays in Uganda contemplate their future under the pall of the capital offence they commit just by existing. And as we think in doleful memory of the ghost of fashion designer Edwin Chiloba, who was murdered in Kenya’s Rift Valley some time between 1 and 6 January, three years ago. Tortured, slaughtered and dismembered, piled into a large metal box and dumped unceremoniously at a roadside from a vehicle without registration plates. For being gay.

I have been in correspondence of late with James Wandera Ouma, a Tanzanian LGBTQ+ activist who has been asking how it comes that Africa is so bent on upholding moral codes imposed by such immoral colonial masters. Here is the nub of our conversation:

I wrote: I have struggled with modern African attitudes to homosexuality and written about them on my blog (here are two such articles: https://endlesschain.substack.com/p/the-price-of-safety-the-greed-of and https://endlesschain.substack.com/p/homosexuality-and-money-laundering).

It is true that Britain exported its morals [I eventually reverse this view, see below]. But, strangely, so did France, which had very different views to Britain. For example British East Africa forbade homosexuality in 1897. But the French colonies were released from any existing prohibitions in 1791, when the new Criminal Code was promulgated after the revolution (globally, the first pro-gay reform). All French colonies, just as France herself, were freed from anti-gay laws, by default, since the prohibition against sodomy was absent from the new Code. Six years after achieving its independence from France, however, Senegal introduced a prohibition against homosexuality. So, was that done under pressure from the former colonial master, or was it an own initiative?

I stand perplexed, however. I would be arrogant to say that my life’s acts, those that favoured me and those that others might castigate me for, and which I might myself regard as errors, failures, were impelled by my unerring moral stance. But only I would know the extent of my arrogance. You would not. Because you cannot judge me according to my morals, only according to your own. “I have no window to look into another man’s conscience,” says Thomas More in the play about him.

What impels my moral conscience is my belief that I shall one day have to answer for myself before my Maker. But can I be allowed a certain degree of cynicism vis-à-vis the posit that a government, or a parliament, marshals its law-making activity in line with moral considerations?

Put bluntly, politicians adopt legislation for reasons that go far beyond morals. The very least of them is a perception in their minds that the moral stance will win them favour with benefactors or electorate. A moral law is no carrot. It is most definitively a stick. But I’m not convinced I am right on that.Because I too have no window to look into men’s consciences.

James replied: You are right: none of us can see into another person’s conscience. Moral certainty about others is always limited, and Thomas More’s line captures that humility well. Personal moral judgment should never pretend to omniscience.

Where I differ slightly is in how this applies to state power. An individual may live with moral ambiguity; a government cannot. When the state legislates, it does not merely express values—it authorizes force: arrest, imprisonment, exclusion, fear. That is why laws must be judged less by claimed moral intent and more by their actual consequences.

You are also right that politicians rarely legislate from pure morality. History shows that so-called “moral laws” often serve power—winning votes, pleasing benefactors, controlling those seen as inconvenient. Morality becomes a language, not the motive.

This is where the “stick” matters. When a law punishes identity rather than prevents harm, it stops guiding conscience and starts coercing it. If we cannot see into consciences, should we not judge laws by what they do to human beings rather than what they claim to represent?

It seems obvious, but the commentary on Out of Africa sheds a light that leads me to realise the British never exported any moral code to Africa. To conclude that the British had a moral bone in their bodies is to fall into their trap: the anti-gay laws they implanted there had one goal only: to secure Africa as a source of economic extraction. How silly of me: follow the money; why, of course.

“Denys [Finch Hatton] deeply admired the unique qualities of the Maasai and he tried to help them when the colonial government took away their spears and shields, robbing them not only of their ability to fight, and thus stop lions from raiding their herds, but also of their identity. The British plutocrats condemned because they could not comprehend a race that did not define itself by its economic utility.”

I cannot comprehend one—mine—that does.

James again: Sections 154 and 157 of Tanzania’s Penal Code are not African in origin. They were introduced through the Penal Code Ordinance No. 11 of 1930, enacted during British colonial rule when Tanganyika was a League of Nations Mandate. Legislative power rested entirely with the British administration, not local institutions.

The Penal Code was enacted under the authority of the Governor and Governor-in-Council, acting for the British Crown. At the time, Sir Donald Cameron was Governor. The law was largely copied from British imperial models, especially the Indian Penal Code of 1860, which explains the Victorian-era language such as “carnal knowledge against the order of nature.”

After independence in 1961 and the union with Zanzibar in 1964, Tanzania retained much of this colonial legal framework. Sections 154 and 157 remain in force today, often mistakenly defended as African values, yet they are colonial imports—products of British law and Victorian morality, not indigenous African customary law.

The key take-away here is that colonial powers in Africa may have romanticised about the native populations, may even have conferred rights on them (the rights they had initially denied them, of course) and extended benevolence to them, but in the end, when push comes to shove, they saw Africa, and see it still, as an economic wealth-generator, and those Africans who are deemed most deserving of western magnanimity are those who support the wealth-extraction models that colonial powers initially imposed by the front door, and now impose by the back door. What it is exactly that impels the vast majority of Africa to maintain its colonial anti-gay laws is a matter that James can better answer than I can.

All I can do is to return to pondering the title of Blixen’s mémoire and Sydney Pollack’s film: Out of Africa. If we want Africa to have a happy new year, then we should perhaps think more about what we will put into Africa, rather than extracting out of it. You have the links to James, and to Abs. They live farther apart from each other on the African continent than it is from me to Abs in The Gambia, and yet they are still both Africans, with African values and African ancestors.

They may need our help, but they don’t need our education. We so often vaunt you get out what you put in. So, this year, put something into Africa.

Image: Umbrella thorn acacia in the Serengeti, Tanzania.