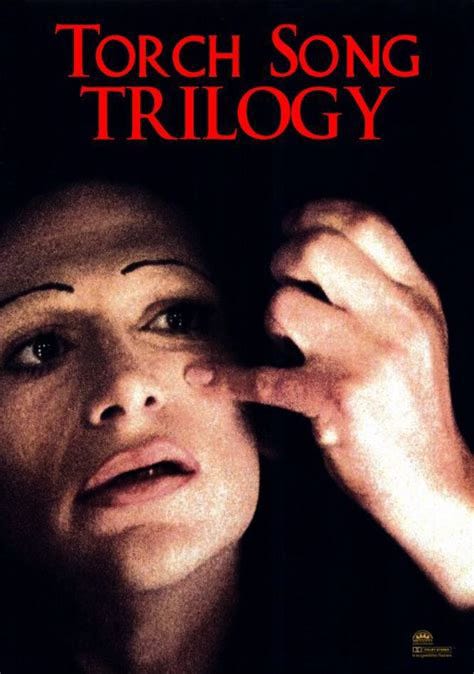

For the umpteenth time, I’ve rewatched Harvey Fierstein (Germanophiles do note: Fire-steen, it’s pronounced) in Torch Song Trilogy, a play (three plays, in fact, as the title suggests) that he wrote and turned into a film and starred in when he was young and thin. He’s adorable in it. As is, of course, Matthew Broderick, who is adorable in everything he does. He’s probably adorable doing woodwork. In fact, I’m pretty sure he is.

Torch Song Trilogy features misfits. People who don’t quite fit. Who stick out, saliently, like a sore finger. I have a sore finger right now, and I can assure you that everything I hit, I hit with it. So, sore fingers certainly do stick out. The misfit characters in this two-hours+studio-insert-long movie are the straights and the lesbians. And the stars, the queens of the show, that’s the gays.

What the film in large part does is wittily and heart-rendingly show how very possible it is to coexist with others in a throbbing city, in a close family, in a multicultural neighbourhood, and yet have little to no understanding of how one’s fellow citizens function. To the point of killing them.

The film was made in 1988 and I first saw it at a friend’s flat in Germany in 1991, under the title Das Kuckucksei—literally “The Cuckoo’s Egg”. Broadly autobiographical, the film strikes a number of chords with me, not least with its gay theme. Fierstein is nine years my elder and, in the time when the film is set, that made a huge difference. We were of completely different generations and the first act of the film trilogy is set in the years 1971 to 1980, which were school years for me and years in which Harvey ventured out into the world.

I decided to re-watch the film with Harvey’s voiceover commentary (which is how I know the film is exactly two hours long + the insert). He explains how the actual timespan of the storyline was massaged to avoid the era of AIDS: this is a pre-AIDS story about gay men. In discussions with the film studio, the executives asked, “What about the angle on AIDS?” and Fierstein had some difficulty in persuading the studio that AIDS was irrelevant to this particular story. As he says, just as every post-World War II film had to reference back to the war (if it wasn’t already about the war), it was expected that every gay film of the 80s would reference AIDS. He responded by saying, “New York’s straight population is experiencing rampant syphilis infections. Does that mean every straight film that’s made has to mention syphilis at some point?” They massaged the time line, instead.

And that, interestingly, is pretty much what the film did all the way through: even as a fictionalised account of elements of Fierstein’s life and recollections, woven into a dramatic presentation, it massaged reality. Just as gays in reality also have to massage … reality.

Last year, I met a disabled person on line, as part of a language course I was teaching. As a project, I asked the participants to prepare a presentation about something on which they were passionate. One spoke about Buddhism, one about her native country of Morocco, and one about carp fishing. The disabled man spoke about being disabled. “People should all experience one day,” he said, “just one day—in a wheelchair. Then, they might understand.” These are sentiments I would also echo for being homeless, penniless, jobless, an immigrant, a victim of injustice, gay. Is it so hard to imagine being someone else; the person you dislike?

When a film is made, they do test showings, to gauge the response of the audience, and they test-showed Torch Song Trilogy in Hollywood. It came back with 90%+ ratings. Astonished by such a positive feedback, they re-tested it at a cinema in another state than California. The test reaction was the same. It was an absolute winner.

The film was not about AIDS. It never mentions the word. But it was released mid-AIDS crisis (retrovirals wouldn’t be introduced until the early 1990s). Studios all across Hollywood prepared their own gay-themed film projects, encouraged by the positive test results for Torch Song. In the end, however, the film only became well-known through television and home entertainment. In the cinemas, it bombed.

Fierstein attributes the disparity between the test results and the box office take to a heterosexual mindset that has no idea how to market a gay film. One wag published a cartoon that also said something about why it was eschewed: outside a multiplex movie theatre, two guys are deciding which film to go to. About the line of people waiting for Torch Song, one says to the other, “I’m not lining up with a bunch of queers.”

Harvey Fierstein has been active in theatre, movies and activism since the age of 15. He is an ardent voice for gay rights and the commentary that he gives about his film is amazing and non-stop. He is full of wit and insight and names, and he can even remember nicking the carpet off one of the sets. For two hours, he becomes your best friend, whether you’re gay or no.

As I say, when Torch Song came out, the gay communities were in the AIDS crisis and New York was also in its syphilis crisis. No doubt you don’t hear that much these days about the New York syphilis crisis, but it is still there. The AIDS crisis became HIV and U=U, provided you take retrovirals for the rest of your life.

COVID, when it came along in 2020, would become long COVID and, for many, “it’s just like the ’flu, anyway.” But the world still went into shut-down. When HIV hit in 1981, Harvard University told the US government to ship all gay men to an offshore island and lock the gate. Gay men looked at COVID and asked, “You mean you straight folk can’t cope? Jeez.”

For millennia, the preferred manner of dealing with something you don’t understand has been to eliminate it. To castigate it, to cast it out and cast it as the villain. In only one scene of Torch Song do Arnold and his mother, played by Anne Bancroft, have a kind word for each other. Arnold yearns for the understanding that exists between his mother and his father; his mother yearns for a son who isn’t gay. In commenting on the brilliant last scene of the film, in which Bancroft and Fierstein go to emotional depths that harbour energy-sapping dangers for an actor, Harvey reflects that the two characters at no point come to a mutual understanding of each other’s make-up. But they do arrive at a mutual understanding of each other’s pain.

Fierstein is upbeat about gay rights, but, then, his commentary does date from 20 years ago. I mean, we’d by then progressed from New York police not even recording assaults on gay men to them at least writing a report. But the victimisers can’t leave it, and the position of gays is now regressing again. This time, the regression is shared by rights in other quarters: reproductive rights, Blacks and the police, asylum, protestors, energy consumers, protectors of the environment. And the drag queens who feature so prominently in Torch Song are under attack as well.

If Shakespeare’s Falstaff believed that discretion is the better part of valour, then gay men in the 21st century know only too well that discretion is the better part of survival. Not, for many, survival of life’s rat race, but simply survival.

Survival, rights, politics, obligations: they’re all part of the great game of enough. To score a goal in football, the ball must be in the goal enough; to make the grade in school, you must be schooled enough. To live the life of the wealthy, you must be wealthy enough. To stay out of prison, you must be innocent enough; to go there, guilty enough. But, to be gay, you must be straight enough. Nowadays, being gay is the only state that you can survive in by sufficiently being its opposite.

Torch Song Trilogy’s second scene is set in a theatre, where Arnold is putting on his make-up as a female impersonator, and opening his heart to the audience via his dressing-room mirror:

[New York 1971]

I think my biggest problem is being young and beautiful. It’s my biggest problem because I’ve never been young and beautiful. Oh, I’ve been beautiful; God knows, I’ve been young; but never the twain have met. Not so’s anyone would notice, anyway.

Y’know, a shrink acquaintance of mine believes this to be the root of my attraction to a class of men most subtly described as ‘old and ugly’. I think he’s underestimating my wheels: y’see a ugly person who goes after a pretty person gets nothing but trouble; but, a pretty person who goes after a ugly person gets at least a cab fare. Now, I ain’t sayin’ I never fell for a pretty face, but when les jeux sont faits, give me a tope with a pot of gold, and I’ll give you three meals a day, ’cuz, honey, there ain’t no such thing as a tope when the lights go down: it’s either ‘feast’ or ‘famine’. It’s daylight y’gotta watch out for. Well, face it: a thing of beauty is a joy till sunrise.

There’s another group y’gotta watch your food stamps around: the hopeless. They break down into three major categories: ‘married,’ [knowingly] ‘just in for the weekend’ and ‘terminally straight.’ Those affairs are the worst! Y’go into them with your eyes open, knowing all the limitations, accepting them maturely, and then, wham! bang! You’re writing letters to ‘Dear Abby’ and you’re burning black candles at midnight, and y’ask y’self, “Wha’ happened … ?” I’m gonna tell you ‘wha’ happened’: y’got just what y’wanted. The person who thinks they’re mature enough to handle an affair that’s hopeless from the beginning is the very same person that keeps the publishers of Gothic romances up to their tragic endings in mink.

[Holds a purple veil up to his face] Whaddaya think? Gorgeous, huh? … [Drops the veil] Gimme a break! It’s still under construction.

For those of you’s who haven’t yet guessed, I am an entertainer. Or what’s left of one. I go by the name ‘Virginia Ham’. Ain’t that a kick in the rubber parts? You should hear some of my former handles: Anita Mann, Fonda Boise, Claire Voyant, Fae Ways, Bang-Bang LaDesh … Yeah, I’m among the last of a dying breed. Well, once the ERA1 and Gay Civil Rights Bills have been passed, me and mine are findin’ ourselves swept under the carpets, like the Blacks done to Amis Handy and Aunt Jemima. But that’s alright. Hey, I’ve always said that, with a voice and face like this, I got nothin’ to worry about: I can always drive a cab.

[Serious] Y’know there are easier things in this life than being a drag queen. But I ain’t got no choice. Y’see, I’m … try as I may … I just can’t walk in flats. [Uproarious guffaw]

Y’know, there was one guy once—his name was Charlie. [Dreamily] Oh, he was everything you could want in an affair, and more: ooh, he was tall … handsome … rich … deaf—[explaining] the deafness was the ‘more’. Well, he never yelled at me, never complained if I snored; all his friends was nice and quiet. I even learned me summa that deaf-sign language. Oh, oh, oh, I remember some:

[Signs] That’s ‘cockroach’.

[Signs again] Means [sotto voce] ‘f’ck’.

Oh, this is my favorite: [Signs] means ‘I love you.’ And I did, too. But, [signs] not [signs again] enough.

[Goes to leave the dressing room. Turns at the door.] You know, in my life I’ve slept with more men than are named and numbered in the Bible, Old and New Testaments put together. And not once has someone said, ‘Arnold, I love you’—[ironically] that I could believe. And I ask myself, ‘Do you really care?’ [Laughing back a tear] You know, the only honest answer I can give myself is: ‘Yes. I care. [Regains composure] I care a great deal. But [signs] not [signs again] enough.’

Here’s Harvey Fierstein singing in the movie.

Equal rights amendment to the Constitution (it was never ratified).

The Torch Song Trilogy is one I've never seen. I wish life wasn't so difficult for people who are 'different' from the so-called standard. Why the hell is who you love anyone else's business? Being gay isn't a disease - you can't catch it. Men are either gay or they're not. What difference does it make? I have two great-nieces who are lesbian. I love them the same as all the rest of my nieces and nephews.

The only people I despise are those who are hate full, vicious, cruel. People like Kim Jong Un, Netanyahu, Putin, Trump, Xi, Gaetz, Mike Johnson, et al.

I think it's pretty obvious Graham that you are, or at least seem to be a good person. That's all I need to know.