A few weeks ago, I went to a ball game. Baseball in Brussels. A friend of mine plays, and his team play in a league. I didn’t get to see a home run, but I did get a chance to sing, “And it’s root, root, root for the home team: if they don’t win, it’s a shame.”

It’s a shame. Shame is an ancient word, from the first millennium, derived from Swedish skada, which broadly means harm, disadvantage. It came into German as Schade and its idea came into French from a different direction as dommage. It’s a word whose precise nuances can vary greatly, and, in all languages, it’s found its way into everyday expressions that make of it a less-than-obvious word to translate. Les dommages-intérêts (damages in a court action) is far removed from quel dommage ! (what a pity!). According to Van Dale, the etymology of its Dutch equivalent in this sense, jammer, is unknown: jammeren means to lament, complain, and the link to wat jammer! (what a pity!) is direct; but the Dutch approach is to regard what provokes the utterance as something to lament about, rather than something of objective disadvantage. In that, Dutch takes the more subjective route, and perhaps rightly so: the expression is grounded in the utterer’s viewpoint.

The precise spur to uttering it’s a shame is generally provided by surrounding context. One might imagine a number of subsequent phrases:

I was counting on that so I could make progress. You’ve let me down.

Never mind. It was a nice-to-have but not a must.

What a waste. You’re incompetent.

The point in such utterances at which shame starts to take on another meaning is a fine point of interpretation: you should be ashamed of yourself. If it is true that pride comes before the fall, and it may be questioned how far before the fall its onset occurs, then shame should be that which swiftly follows the fall.

The people known as the Pennsylvania Dutch, Amish, and Fancy Dutch communities of North America eschew pride. They originated in 17th century Germany (and not, as the name might suggest, the Netherlands),1 a break-away group of Mennonites (named for Menno Simons (1496–1561)) who followed the Swiss leader Jakob Ammen (whose followers became the Amish), ultimately to Pennsylvania, in the second quarter of the 18th century. The Amish reject the baptism of infants and place far greater emphasis on the conscious decision to be baptised at a later, more mature stage in life: the Greek for new baptism gives us the name Anabaptist.

I am not myself Anabaptist but I was rebaptised, in the sense that, although baptised as an infant, I made a conscious reaffirmation of faith at the cathedral of St Giles in Edinburgh, during my studies at the varsity. Whether called Anabaptism or rebaptism, it is much more than simply a confirmation of belief, especially for those who are not raised in an Anabaptist community; it entails a great deal of internal struggle and reconciliation, between tenets of civil society, customs, habits and laws, church practice and social living, especially those which entail the abandonment of those guilty of folly, ideas of recrimination and revenge, and the notion even of defence. Far from being the culmination of cogitation about all these aspects of life, it was, for me, my embarkation thereon.

Self-actualisation is a process that humans go through, unlike the animals with which we cohabit our world. Dictionaries set out its common meaning: the achievement of one’s full potential through creativity, independence, spontaneity, and a grasp of the real world, in the words of one. I think it goes farther than that. It is, in its basic form, the process that distinguishes us from animal life,2 by which we come to recognise ourselves when we look in a mirror; in its more sophisticated form, however, it is not to recognise that we are what we see in the mirror, but to recognise that what we see in the mirror is who we are. The step between the two is self-actualisation; and recognition of the point of self-actualisation serves little or no purpose, unless it be pursued by action consequent thereon – failure to pursue which reflects, contrarily, the reality that self-actualisation has not been achieved. Self-actualisation, therefore, is a step that gets clouded by aspects such as pride: pride reflects a sense of achievement, and anyone who achieves self-actualisation knows one thing about themselves: that they haven’t achieved it.

Belief is more than belief in God. It is belief in something that is beyond belief, and therefore in something that is unachievable. Whilst belief is often dismissed as a delusion, few believers can profess a state of knowledge of what they believe in that is perfect. In that sense, non-believers are right to call believers deluded. What marks the believer out from the non-believer is not therefore belief itself, but the believer’s recognition that, if they achieved self-actualisation, that would per se be delusion. They who make enquiry of their belief and confront themselves with the ineffability of God come closer to understanding, but simultaneously recognise how far they still are from comprehending.

For the non-conformist, this is a struggle. The early Swiss and Palatine non-conformists, who paid with their lives for their non-credence in the established church, fought to establish movements, to cultivate followings, because the 16th century was a time in which no man counted alone and when the established church held huge sway over lives. Not just how they were lived, but whether they lived. In the modern era, association can still be a dangerous thing, or it can be a comfort, in the knowledge that one combines with like-minded. The only true freedom lies in thought, and the non-conformist can take great comfort from their freedom of thought from the trammels of any church, established or non-conformist, as can the non-believer.

But anyone who formulates thought can yet be challenged to deny their thought, by way of actions impelled by social custom or law. The quest for self-actualisation cannot be advanced by denying in practice the progress booked in the mind. “What is an oath, but words we say to God? When a man takes an oath, he’s holding his own self in his own hands. Like water, and if he opens his fingers then — he needn’t hope to find himself again.” Thomas More’s words to his daughter in the play A Man For All Seasons by Robert Bolt, in response to Meg’s exhortation, “Say the words of the oath and, in your heart, think otherwise.” Is hypocrisy a sin? If it isn’t in dealings with Man, it is in dealings with God.

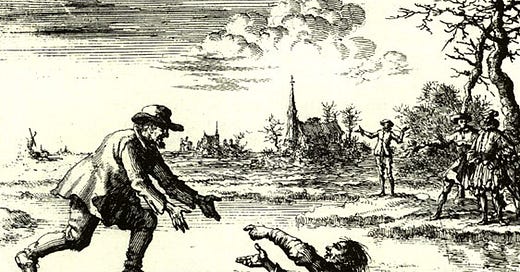

Image: Dirk Willems rescues his pursuer. By Jan Luyken - https://mla.bethelks.edu/holdings/scans/martyrsmirror/, image, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=544931]

A common wedding present among the Amish is the book The Martyrs’ Mirror: it’s a 1,300-page account of those who died rather than renegue on their faith, often at the hands of the Roman Catholic Church and even, in England, of Anglican authorities. Illustrated above is the rescue by Dirk Willems of the guard who pursued him after noticing his escape from the prison where he was being held for his Anabaptist views. As the result of his act of mercy, Willems was re-arrested and burned at the stake. He did not once disavow his faith or his practice of it. For an Anabaptist, nobody, not even the most evil, deserves to die. It’s a hard tenet to take with one through life, for it may inevitably lead to one’s own death; and yet it is an extremely simple tenet to adopt: that judgment lies not with Man, but with God. The believer who adheres to tenets such as these has a belief so fervent that the prospect of his own death will not sway him from observing God’s law on Earth, for the – to him – simple reason that no life on Earth in disobedience of God’s law can compare to life in Heaven after a life spent on Earth in observance of God’s law.

It’s a spirit that is in fact captured in Niemöller’s well-known poem First, they came … The English will be familiar to the reader.3 Here’s the original German:

Als die Nazis die Kommunisten holten, habe ich geschwiegen; ich war ja kein Kommunist.

Als sie die Sozialdemokraten einsperrten, habe ich geschwiegen; ich war ja kein Sozialdemokrat.

Als sie die Gewerkschafter holten, habe ich nicht protestiert; ich war ja kein Gewerkschafter.

Als sie die Juden holten, habe ich geschwiegen; ich war ja kein Jude.

Als sie mich holten, gab es keinen mehr, der protestieren konnte.

When the Nazis came to power, Martin Niemöller was, by his own public confession, antisemitic. By the time he left prison, he was no longer antisemitic, but he was anti-Nazi, anti-government and, even, anarchistic.4 He pleaded for Germans to accept their guilt in having passively acquiesced in the Nazis’ reign of criminality, for which he was jeered and heckled in Erlangen, Marburg and Göttingen. As a Lutheran pastor, he did much to atone for his complicity as a bystander during the Nazi period; in how far, I do wonder, would he have preached the gospel of shame to his fellow Germans had he been a Mennonite?

Image: German pastor Martin Niemöller.

Reported during a 1954 visit to Japan, Niemöller said, “The renunciation of war as expressed in the Japanese Constitution has given a first ray of hope to a world in darkness and despair, and men today cling to this hope passionately. Can we really do something about it or are we to stand aside as idle onlookers, unable to contribute for better or for worse?”5

These are words of huge relevance in the light of the Russo-Ukrainian War, for belligerents, onlookers and pacifists alike. One Ukrainian pacifist of my knowledge has found a means to contribute to his country’s cause, without lifting arms in its defence, and I am left to conjure the strange juxtaposition among Dirk Willems, who aided his enemy at the cost of his life, Martin Niemöller, who acquiesced in his enemy, very nearly at the cost of his soul, and Vlad Beliavsky,6 who fights his enemy whilst preserving his pacifism entire and whole.

Image: Ukrainian philosopher Vlad Beliavsky (The Guardian).

In 1985, I made my first trip to the United States and was invited by friends to stay a while with them in St Mary’s, Ohio. It was the year of Harrison Ford’s film Witness and, when my hosts asked what specialties they could offer up, I voiced three wishes, all of which they fulfilled. Cheryl cooked up a pecan pie – at no small expense – which was a dish I’d heard of in films and on TV. They arranged a cook-out one day, at which a fellow guest for the first time in my life identified herself as Palestinian, which spurred me to a discovery of things that have now resulted in the protests we are seeing in Israel.

I hadn’t in fact appreciated how easily my third wish could be fulfilled. Across the state border in Indiana was an Amish community. Whether they needed to or not, they offered an outreach service in the form of arranged visits, probably to assuage the rubbernecking curious in their desire to stare and gawp at these supposedly anachronistic inhabitants of modern America. My hosts packed me into their car and off we went to learn about another side of the tracks where there are not even any tracks.

When I later wrote my journal for the day, one word suggested itself to me and suggests itself still to me to describe these Amish people: wholesome.7 Although divesting myself in my later middle age of some of the trappings of modern living might come easily – television and mobile phones in particular – I don’t think I could adjust to a life such as theirs, in which pride is eschewed so absolutely, that even buttons on clothing are taken as showy and vain, and garments are held together with hooks and eyes. The Mennonite way is not for me. But it still has much to teach me. And, if its teachings come to rest in me, and I truly learn from them, I know that I will make of myself an enemy to many in the society in which I live.

In his cited article, Unruh names Mennonite teacher Calvin Redekop’s8 eight concepts defining Anabaptism. I can find myself in many of these, as I can find myself in Martin Niemöller, and I can certainly find myself in Vlad Beliavsky.

1) A Holy Disciplined Church/Community, which implies the submission of the individual goals and drives to the collective/social system.

This is a common excuse for totalitarianism, impinges on the direct communion with God professed by other Protestants and sits hard with me. Pass.

2) Separation from the World and the State, implying the fundamental Christian dualism between the religious and the profane realms.

The objection to this is of practical dimensions, but not philosophical. This I agree to. The problem is not the separation of church and state, but of state and other matters that get vaunted as if they were religions.

The worst excesses of church power, where the church exercises nothing more than political autocracy over its flock, are a pure bastardisation of belief. Anabaptism, by contrast, is only able to commit to its belief by separating its flock from the real world.

Both of these are sad conclusions: that the state will only tolerate belief up to the limits that it sets, in its own discretion, on its own tolerance; and it will embrace belief otherwise only as a tool of control; and, by contrast, that the Anabaptist’s belief, as a mark of their control by none other than God, must be exercised in utter separation from the state, which otherwise views the Anabaptist as posing a threat to it.

It takes some sinking in: to the state, those who through faith will not raise a hand in their own defence, who will risk life and limb to save their enemy, who shrink from any act that constitutes unity in pride are … the enemy.

3) Voluntary Church Membership, implying the fundamental worth and autonomy of the individual.

This is the basis of Anabaptism. By creating default membership of the church, one makes it an opt-out option; so, as long as the church was the state, its hold over the citizen was secured from birth. The opt-out becomes a real choice, but a dangerous one, for the likes of Dirk Willems. Nowadays, it’s generally less of a problem, even though it’s still required to opt out of church tax in Germany: the default is that you pay it. Bank accounts used to be opt in. Now, in Europe, they’re almost opt out. And, if you do that, just try to function in the modern EU. What do opt in and opt out even mean where the barriers to exercising an option are so impenetrable? But, here, I agree: opting in more readily rules out doing so nonchalantly.

4) Ultimate Obedience to God, Jesus and the Scriptures, which implies the locus of authority in the transcendent rather than in the human sphere, and reminds and warns us of the awesome horror of the arrogation of power by individuals and groups.

The awesome horror of the arrogation of power by individuals and groups will not cease if I myself recognise God’s ultimate authority; it is likelier to cease if he who arrogates power to himself would do so. Acquiescence in the wielding of power is said to be the route, not to self-actualisation but to self-preservation. And yet Jesus teaches us that there is no self-preservation unless it be in the embrace of God. I wonder, if Niemöller were here, what would he say?

5) An Ethical Faith. This element guards against the subjectivity and spiritualisation of religion.

Ethics are malleable and, knowing the Anabaptists as I do, I know that theirs are of the most stringent sort. Subjectivising is precisely what I’m doing here. Ethics are an imposed standard and I wonder in how far any imposed standard on the thought of him who does not form part of a community – and can only therefore be overseen by him, himself – even needs to be in place. I accept that I will never be perfect.

6) Discipleship and the Simple Life focusing on the importance of doing (obedience) rather than simply being.

Do, don’t just be. Inspired by Nike? No, but even corporate conglomerates can hit the mark, if only by accident.

7) Mutual Love and Caring, implying the universal reality of the interdependence of all created and living things.

Our care and understanding often – even at its best – extends only to our fellow Man. Our disregard for the world is coming now to haunt us. Vehemently yes to this.

8) Love and Nonresistance, which implies the positive implementation of the negative rejection of human power and authority commanded in #4.

This is Niemöller’s answer; and mine.

The question that remains with me as I close is to what extent failure by me to meet any of these high standards that have been set by others I can view, for me, myself, as being a shame; and to what extent my failure is to be regarded by me, myself, as shameful.

The self-actualisation is a work in progress. And will always be so.

The English word Dutch is a corruption of deutsch (German for German), both in these appellations and in references to the Netherlands, where the historical dialect of Low German is still spoken, as it is as far east as in Poland.

In the 1951 John Huston film The African Queen, Rose tips Charlie’s gin overboard in the night. Next morning, Charlie remonstrates that it isn’t natural for a man to be expected to make the day through without a drink. Rose responds with, “Nature, Mr Allnut, is what we were put on this Earth to rise above,” a far from irrelevant truth as the two of them make a bid to escape from First World War-torn German East Africa.

From the 1972 edition of Thieleman van Braght’s 1685 Martyrs’ Mirror, sourced at A Story of Faith and the Flag: A Study of Mennonite Fantasy Rhetoric by Mark Unruh (Mennonite Life, September 2002, Vol. 57 No. 3):

“In the year 1569 a pious, faithful brother and follower of Jesus Christ, named Dirk Willems, was apprehended at Asperen, in Holland, and had to endure severe tyranny from the papists. But he had founded his faith not upon the drifting sand of human commandments, but upon the firm foundation stone, Christ Jesus. He, notwithstanding all evil winds of human doctrine, and heavy showers of tyrannical and severe persecution, remained immovable and steadfast unto the end. . . .

“Concerning his apprehension, it is stated by trustworthy persons, that when he fled he was hotly pursued by a thief-catcher, and as there had been some frost, said Dirk Willems ran before over the ice, getting across with considerable peril. The thief-catcher following him broke through, when Dirk Willems, perceiving that the former was in danger of his life, quickly returned and aided him in getting out, and thus saved his life. The thief-catcher wanted to let him go, but the burgomaster very sternly called to him to consider his oath, and thus he was again seized by the thief catcher, and at said place, after severe imprisonment and great trials proceeding from the deceitful papists, put to death at the lingering fire by these bloodthirsty, ravening wolves, enduring it with great steadfastness, and confirming the genuine faith of the truth with his death and blood, as an instructive example to all pious Christians of this time, and to the everlasting disgrace of the tyrannous papists.”

Oh, Ye of little faith (https://endlesschain.substack.com/p/oh-ye-of-little-faith).

“For politicians, truth and falsehood are unimportant. So, I never could become a politician.”

My journal records the following (from July 1985):

“The Amish are plain people who shun any aspect of life which may inculcate pride or vanity. Deeply religious, they are a sub-branch of the Mennonites, but they choose to live the agrarian life of their forefathers, back in the 1600s. There is no such thing as a typical Amish way of life, for each ‘bishop’ makes his own rules for his community, which may drastically vary from one district to another. A district comprises as many people as can comfortably be accommodated at a prayer meeting, so that, in cases of over-population, one district may be split into two and a new bishop appointed.

“There are no churches — the meetings take place in people’s houses, each family (which can number from ten to 25) taking turns to host. The meetings take place every other Sunday, the intervening Sundays being for the purpose of family reunions, the reasons being that travelling to ‘church’, cooking and eating for such a large number could not practically be accomplished in one morning.

“In the home, life is that of the farm — all food is home-grown or bartered with other Amish (which, by the way, is pronounced ‘Ah-mish’). They have no fridges, so food is preserved by bottling in Kilner jars (or what Americans call ‘canning’). Decoration of the home is limited to a few growing plants, not cut flowers, no paintings, no ornaments. Furniture may be decorative, but not flamboyant, and chairs there are in abundance, for it is the custom to be seated at the family reunions. There are no carpets; curtains are simple and unlined, being permanently hung over the windows, attached to one side when one is ‘at home’ and left hanging when visitors are unwelcome. Lighting is by oil or paraffin lamps and heating by a simple stove, besides the cooking range. The house has many windows, for light in winter and coolness in summer. The ceilings are low and wood-lined for insulation, though some bishops will allow folk to take up local authority grants for insulation.

“Next door to the main house is usually the ‘Großvater House’, or house where the grandparents live. There, they are independent, but close enough to allow the family to take care of the old folk. Nearby is also a windmill and a curing/canning house. The folks drive horses and carts — in some areas convertible, in others open all weathers (according to the bishop’s whims). The Amish may not own a car, but may travel in someone else’s (for there is no pride involved in merely travelling in a car). Similarly, they are pragmatic enough to use non-Amish dentists, doctors and opticians. Opticians particularly, for all Amish seem to suffer from bad eyesight. This is because they marry only amongst themselves and there is in-bred amongst them a sight deficiency, brought over with the first German-Swiss in the 17th century.

“They wear simple clothes, with little choice of colours and no zips. Buttons may in some areas show, in others not. Everyone wears a hat: straw or felt (men) or a bonnet (women). Music is a no-no and anyone who assumes non-Amish lifestyle can never be reconciled and must ever be shunned. Similarly, no non-Amish person can become Amish — you must be born into the lifestyle.

“I was fascinated by the whole idea. I summed up their ethic in one word: wholesome. A good life, well-lived and in the service of God. Okay, they do little benefit to mankind as a whole, but how many are there in our own society who benefit mankind and put themselves second to the greater good? Few, indeed. On the contrary, the Amish live in the service of each other. They have no insurance: if their house burns down, the neighbours will replace it; if a crop fails, the neighbours will victual the beleaguered family; if a husband dies, the family will sustain the widow.

“Most families have huge fortunes stashed away in banks, but which never get spent. I suspect that, in another 50 or so years, when the culture starts to crumble, the families will have amassed so much that they will then be able to buy the State of Indiana lock, stock and rain-water barrel. Until then, they are a law unto themselves. They are not subject to state taxes, education laws or most other regulations, simply because they are so effectively self-regulating, law-abiding and pose no threat to, or burden upon, conventional society.

“I got a few photos in of the Amish at work before I began to feel like an intrusion, like some ogling heathen, a staring child who doesn’t know better.

“I admire these people immensely. They are so totally happy and at peace with what they do. I can see no reason why the world would not be a better place if we all lived like that. They want for nothing: health, life, spiritual fulfilment. Oh, they don’t know the joys of fast cars, fridges and convenience foods; TVs and VCRs, tape recorders, art or music. And perhaps they have, by our standards, unhealthily narrow minds, blinkered by their own existence. But they know hardly any crime, a true brotherhood of man, peace with God, hard work, humility, respect and fear, and a life which is … there is no other word for it … Wholesome.”

https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/legacyremembers/calvin-redekop-obituary?id=35922312 (retrieved 26 July 2023, but inoperable 27 July 2023). https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/88393462/calvin-wall-redekop (retrieved 27 July 2023).