If you speak to a Trump supporter for very long, you will generally discover a number of standard traits:

they like Mr Trump

they like Mr Musk

they think USAID and DEI are scams, and it is right to dispose of them

they don’t like vaccines, especially vaccines against Covid-19

the moon landing was a fake

welfare is fantastic, when they’re claiming it

Wait, the moon landing was fake? Where did that one come from?

There’s more: 9/11 was a CIA plot.

Hang on, just a minute, first this: there is one conundrum (because I, like them, see the world in nice, simplistic terms) that I haven’t yet been able to resolve, and it is this: how do they expect a radical system designed to suck cash out of the poor and give it to the rich and rip away all the social safety nets that protect the poor and those who’ve fallen on hard times and exploit workers who are denied union and other protections and do away with protection of their financial investments and protection of the markets they participate in, including banking, to benefit them? They won’t be cleaning up the Gulf of America to detoxify the shrimp for Louisiana fishermen, y’know.

Nine-eleven was a CIA plot? Well, apparently there are buildings that fell down in New York that were hardly touched when the airliners crashed, and yet collapsed like a house of cards, whilst other buildings just next door … didn’t. Suspicious? I’ll give you odd. As odd as the assassination of JFK, followed swiftly by the assassination of LHO, followed swiftly by the death in hospital of Jack Ruby? Yes, about that odd. As odd as the revelations of Edward Snowden? Yes, that odd. Lots of oddnesses. If you had to draw a comparison between the outrage of the killing of JFK and the outrage of Musk’s closure of many US government offices, which of them is more outrageous: killing JFK or wood-chipping USAID? Equal—except we know who wood-chipped USAID, but we don’t know who killed JFK. I think that’s what Musk means with transparency. Yup, I reckon so.

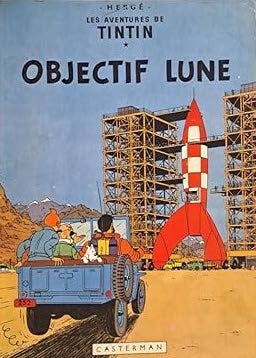

Right. The moon landing. I’ll bet, in all the hullabaloo over the past three weeks, you’ll have lost sight of the moonshot of 1969. Apollo 11. It’s okay, I did as well there, for a moment. Well, a surprising number of establishment-sceptics subscribe to the view that the Apollo 11 moon landing was faked. And my response to that thus far has been to say I don’t really care whether it was faked or not: it was great television! (I was eight and my cousins were over from Canada, and we were enthralled, and so were lots of other people and, in a way, that is the sceptics’ point.) The people who should be worried about whether it was faked or not should be the guys designing the rockets pointed at Russia, the expertise for which was supposed to be won from that expedition to the moon. (No, not this one:

The long trajectory that ended with a moonshot started back, not with a speech by John F. Kennedy at Rice University on my first birthday, but in the 1950s, with a race against the Soviets: Sputnik and Vostok versus Gemini and Mercury. Vostok involved manned spaceflight (wo-manned, as well, not to mention Laika the dog and some tortoises). Truth is, we only have the Soviets’ word for it that they were first to circumnavigate the world from outer space and the first to send a man and a woman into space, and that cuddly dog.

There is, therefore, a possibility that the Soviets faked Gagarin, Tereshkova and Laika, although two of the three of them confirmed their feats, the third died before landing (although she’d likely have said the rumours were barking up the wrong tree).

Soviet cosmonaut Laika.1

That, at least, is what NASA says of the rumours that there was never a moon landing. So, let’s go back to 1961, and the very beginning of the Apollo adventure, to see where this hoax accusation and its refutation all stem from. And I’ll try to get straight to the point. And once I’m there, you can decide for yourselves.

In his book A Man On The Moon: The Voyages Of The Apollo Astronauts (a copy of which I was enthused to purchase at Cape Canaveral back when, and which sceptics denounce as a whitewash), Andrew Chaikin starts by describing the fire in Apollo 1, which occurred on 27 January 1961 and killed the spacecraft’s crew of Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger B. Chaffee. Chaikin cites this disaster as one of the spurs that impelled America to develop what would become Apollo 11, which is in fact interesting. If at first you don’t succeed try, try again! What about: Maybe this is too dangerous to have even tried the first time? Apollo 1 was a frightful tragedy, it showed inadequate design and inadequate emergency preparation, and it made it patent that spacecraft are very dangerous things. The chances that something could go wrong are immense.

Back in the 1960s, a lot of television was broadcast live. Even Julia Child broadcast her cookery programmes live. On one famous occasion, she constructed a sugar basket by weaving strings of thick syrup from a tablespoon over a bowl, which hardened immediately and formed the shape of a basket. As she removed it from the bowl, however, the basket crumbled and broke. Child showed her inimitable mettle by exclaiming, “Oh, dearie me! Well, we’ll just have to start all over again!” And start all over again is precisely what she did, and this time it worked to perfection, to the audience’s utter delight. Over on the BBC, children’s magazine Blue Peter would show us all the wondrous things that could be created with sticky-backed plastic. However, there was always a point in the proceedings where the presenter would set aside what they were doing and reach for a perfect example: Here’s one I prepared earlier. It’s a mainstay of arts, craft and cookery presentations on TV, because of the difficulty of presenting them live without something going tits-up. In the 1970s, we saw the introduction of a TV editor’s facility that allowed them to delay broadcast of a live event for several seconds, to cover things like where an interviewee slips in a naughty word. It became evident very early on in the story of television that live TV was worse than theatre if it went tits-up, if only because the audience was so much bigger. The bigger the audience, the bigger the … embarrassment.

What a relief that Apollo 1 did not have a television audience of millions when it went up in smoke and took three national heroes with it. The Apollo programme is well-known to have given the world Teflon and Velcro, but what is less well-known is that it made two major steps forward in the field of technology that are still of universal application; contributions that are barely recognisable, now or then, but still firsts in their time.

One of these was the fact that so much of the preparation work went out to subcontractors, who needed to tender for the contracts before they were let. This itself led to difficulties in the selection procedure, because the quandary that NASA faced was: should they go for the cheapest, and keep the costs down, with the risk of receiving substandard performance from the contractor; or should they go for the most expensive, as reflecting the likelihood of receiving the very best contract performance? Some think NASA selected on the basis of who offered the biggest kick-back.

In the end, NASA’s contractor selections were based mostly on technical know-how, but they came with something new written into the contract. Until then, subcontracting had been a matter of farming out: you farmed out the work, and the subcontractor did the work and, if it was substandard, you sued them, or sent it back to be redone. With Apollo, that was impractical. If something failed miles up into the sky, you couldn’t just send it back to be re-fabricated. Besides, your astronauts would likely already be dead. So a new way of working was introduced: true intensive cooperation between NASA and the subcontractor. If the subcontractor encountered a problem that they could not easily solve themselves, they were to call on NASA to work together in solving it. That was revolutionary. Some say it was also a way to ensure NASA’s friends got the nice, juicy contracts, under which NASA did most of the work.

The second contribution was the degree of flawless, fail-safe operation that was demanded. It had to be guaranteed to the extent of 99.99992 per cent. That means a failure was allowed once every 9,999,993 times equipment operated, just short of ten million. The problem with this kind of demanding flawlessness is that there is as good as no way to actually test for it. Some say the great thing about this was that no one could prove a selected contractor didn’t meet the fail-safe operation norm. Because conducting ten million non-destructive tests in full simulated operation on one component is hardly practicable. So, although the requirement was there, the guarantee itself was somewhat notional. Apollo 13 and the Challenger Space Shuttle were prime examples that would follow on from Apollo 11 of expeditions that did encounter failure. They were not fail safe, and their travails were broadcast to a viewing television public. In Apollo 13’s case, the men were returned to Earth safely after circumnavigating the moon—that’s what they said in the movie, at any rate. In Challenger’s case, they didn’t make it out of Earth’s orbit. But, in neither case was the TV audience as great as it was for Apollo 11. Sad to relate, space travel was getting to be a yawn for TV audiences by then, but in July 1969, aside from those battling and being napalmed in Vietnam or hungering in Biafra and across sub-Saharan Africa, the eyes of the world were glued to the goggle box to watch America’s ultimate vanity project: 600 million people, one-fifth of the entire global population. In Kennedy’s own words: in full view of the whole world. Nothing, but nothing, could be allowed to go wrong. And, nothing did. Which is wonderful.

To be honest, I don’t know if the hoax theories are right or not. The flags that flutter wrong, or the dust that’s kicked up by the moon boots, or the slowing down of normal action, like some 1920s silent movie, the absence of the stars (and the astronauts’ inability to even remember whether there were any) and the view out of the spacecraft’s window. I don’t know. But I think I know, if it were to have been hoaxed, why it would have been hoaxed: because it was shown on live TV. What’s more: it was being watched in the USSR. For my part, as I said above: I don’t really care whether it was faked or not—it was great television. And it was great television, because it went flawlessly.

One argument that seems especially persuasive, and about which controversy reigns (see the MM2 video below, and the “Debunked” counter-argument), is the Van Allen belts. Girdles of radiation that encircle the Earth and, in which, within very little time, a human being—it is said—would be quite simply microwaved to a frazzle. NASA says Apollo passed through them fast enough for there to be no effect. Sceptics say the passage could never have been that fast. Apollo 11 stayed on the earthly side of the belts, they say, and therefore never travelled to the moon.

On the flip side, let’s suppose the moon landing took place exactly as described. Well, almost exactly as described. Because, when something goes tits-up in live television, you can’t always say “Oh, dearie, let’s just start again.” But you can cut to one I prepared earlier, and, if there was a hoax, I think it was this: there was indeed a moon landing, but it’s just possible that the required degree of flawlessness did not satisfy the needs for absolute perfection in front of an audience of 600 million, and so what the 600 million saw might well have been done earlier.

What this article is about has nothing to do with the moon landing, however. What it has to do with is that absolute requirement for things to work when they need to work. For flawlessness. So, let’s shift scenarios.

It’s 2023, and you’re busy writing Project 2025, the GOP’s blueprint for a second Trump administration. The book is highly detailed, it runs to hundreds and hundreds of pages. It is meticulous. I don’t know, but I wouldn’t be surprised if the fail-safe grade of this project was also something like 99.99992 per cent. And I also would not be that surprised if, with those demands on its flawless operation, similar degrees of flawlessness would be demanded for its implementation, for Project 2025 would have been dead in the water had Trump lost. Strange to relate, once Apollo had landed on the moon, space exploration of the next decade, far from trumpeting a new age, also became dead in the water. And Trump losing is not something for which the GOP could have reached off camera to say Here’s one we prepared earlier. Nor would re-weaving Julia Child’s sugar basket have been a possibility. Trump needed to win, or it was all futsch.

Now, it is well known that hacking systems needs skill, but it’s not impossible. If you have a few hours spare, go and listen to the BBC’s story of how North Korea hacks regularly into places like Sony Pictures, the Central Bank of Bangladesh, and other places where they steal money. Russia hacks into bank accounts as well, and into much, much else. Elections rely on electronic tech activity and, if you want to influence an outcome that is the result of electronic tech activity, you can best be a hacker of electronic tech activity, and we all know who the best tech guys are in Washington. They all had a front-row seat at the Inaug.

Many are saying that Elon Musk bought himself a seat in the US government, and I don’t think that is necessarily right, but I can only speculate, because I’m not a hacker and I couldn’t get the truth out of Elon Musk if I had a burning candle and a rack to strap him to. But, rather than him having bought his way into the government, the government may simply be rewarding him for having assured that the government is even there.

Would it not be beautifully ironic if Trump supporters who cast such doubts on the technical veracity of the moon landing, which may just, indeed, have been parallel-faked in order to ensure its visual success, still firmly believe in the technical veracity of the election results from November 2024, which may likewise have been given a push to ensure their visual success? How do you decide?

They say the Crown Jewels on display at London’s Tower of London are paste. That’s not because the real Crown Jewels don’t exist. They do (I think).2 It’s because the measures guaranteeing the security of those on display can never be fail-safe. And when things need to be fail-safe, you fake them. Like doppelgänger presidents and decoy limousines and … well, The Italian Job remake. Just to be sure.

Now, this all sounds like conspiracy theory. It is conspiracy theory. But what I like about it is that it turns tail against the very people who perpetuate the moon-landing hoax conspiracy theory. In short, if you agree with the Trumpists, and place no trust in the fact that Apollo 11 landed on the moon, as NASA says it did, then you will place no trust in the fact that Donald Trump fairly won the 2024 election. Because you surely cannot pick and choose which conspiracy theories you trust and which you don’t, especially when they’re founded in the same Wizard of Oz-like theory, all smoke and mirrors?

Further reading and viewing below. James Burke’s programme The Other Side Of The Moon is interesting, for the lack of straight answers he’s able to get out of the men who worked at the heart of the Apollo project. If you care; then, you can decide for yourselves. If you can decide, that is.

Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=793939.

Suppose you owned the Koh-i-noor diamond. I know you don’t because King Charles does. It’s part of the Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom, and features in the crown of Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother. It was going to be worn by Queen Camilla at Charles’s coronation, but India, which is where it was before the British got their hands on it, objected, and so the king opted for a less contentious diamond (Buckingham Palace’s words). Note, he did not offer to return it, but then, why should he? His ancestors stole it, so it’s his.

But what if the reason he didn’t return it is because he doesn’t have it? What if the largest diamond in the world were to have been broken down into smaller diamonds and sold off? Well, why would he do that? First of all, I’m not saying that he has done that. But the simple fact remains that the closest anyone can get to the Koh-i-noor is from quite a distance. And narrowing that distance entails coming within a circle of trust: the King’s circle of trust. So inspecting it isn’t easy, unless you’re in. And we know that the crown on display at the Tower of London is a replica. Even the photo in Wikipedia is of a replica. Well, you can’t give India its diamond back if all you have is a replica. But you can realise the value of the diamond by flogging it, or losing it and claiming on the insurance. You can do what you want with a diamond that no one, unless they’re within the circle of trust, will ever see in the original.

The public’s access to the Koh-i-noor is such that the public must take it on trust that the Koh-i-noor is indeed the Koh-i-noor. And trust is something that is complete or defective. Complete and watertight, or questionable and therefore defective. And when trust is defective, it is not public confidence that one enjoys, but selective confidence by individual members of the public, who decide for themselves which bit of information about the institution in question they trust, and which they do not trust. Meanwhile, those within the circle of trust have no alternative, but to trust: The Koh-i-noor is fake. Yeah, sure, and what have you been smoking?

The rationale for stealing jewellery

Image: publicity for the 2006 Leonardo DiCaprio, Jennifer Connelly, Djimon Hounsou movie Blood Diamond. There are very few pure diamonds that do not have a strain of blood running through them.